An outside corporation takes over a treasured local health-care institution.

The drive for financial accountability, or profits, upends the normal way of doing business.

Patients complain, employees flee. A question comes to mind: Can the corporation impose its will without destroying what made the local institution special?

The arrivals last year of Cenpatico, which took over behavioral health from the Community Partnership of Southern УлшжжБВЅ, and Banner, which bought the University of УлшжжБВЅ Health Network, have had unsettling effects in УлшжжБВЅ. While theyтve created higher expectations in some areas, we just donтt know yet whether in the end theyтre going to improve on what we already had.

Despite plans for an expensive new hospital building, doubts about the new operator of УлшжжБВЅтs cherished University Medical Center have been cropping up for months. First there was the billing change in which cancer patients were called days before procedures and told they needed to pay in full in advance if they wanted their usual treatment. That was troubling.

People are also reading…

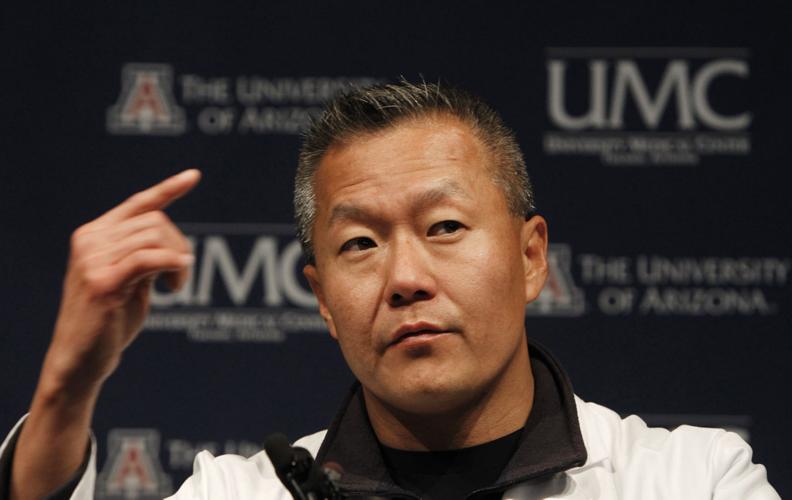

Then, on May 13, renowned trauma surgeon Dr. Peter Rhee . That was a body blow not just for the hospital, but for УлшжжБВЅ, because Rhee in his few years here had become someone we were proud of т a УлшжжБВЅ hotshot who was the face of the team that saved Rep. Gabrielle Giffords in 2011.

He blamed Banner, in part, for his departure to a new job in Atlanta. What bothered him about the changes since Banner took over in March 2015 was what he considered the de-emphasis of UMCтs academic role. The research and teaching performed by faculty members just donтt make the money for hospitals т treating patients does.

тTheir incentives are purely patient-care based,т Rhee told me after word of his departure came out. тIn academia т we normally pay a heavy price.т

That may not sound so bad. Who doesnтt want the hospital focusing on treating patients? But itтs the research and teaching that make academic hospitals special. And itтs what makes them valuable to outside corporations, which are buying up academic hospitals around the country.

тAcademic medical centers have had a halo around them,т health-care attorney Norman Tabler, of Indianapolis, told me last week. тTheyтre regarded as premier institutions in terms of the quality they provide. The buyers want to acquire those halos.т

Buying out academic hospitals, Tabler said, is a national phenomenon тfor the simple reason that theyтre hellaciously expensive to operate.т

The surgery department at UMC has seen significant turnover since and continuing afterward. Thatтs not a coincidence, Tabler and others said. Surgery departments are among the biggest moneymakers at academic hospitals, so itтs crucial to companies like Banner that they have the people they want in place.

Surgeons are notorious for their egos and independence, which runs against the centralization companies like Banner demand in order to bring costs under control.

тThe tradition in academic medical centers was each surgeon decides, for example, what implants the hospital will acquire,т Tabler said. Under new ownership, тThe hospital could concentrate on buying the implant from that volume buyer and get a discount.т

This also bothered Rhee.

тIf you want anything, you have to beg and beg and wait for a centralized committee somewhere,т he said. тThey believe in centralization, not peripheralization.т

Cenpatico also has become known for centralized standards and dictates since it took over from CPSA in October. That homegrown agency had a 20-year run as Pima Countyтs regional behavioral health authority, or RBHA (pronounced тREE-bahт) in this area till then. These authorities distribute state money for treating people with mental illness and addiction to the agencies that treat them.

The way CPSA did it opened up the authority to accusations of inefficiency: CPSA would fund agencies like La Frontera, CODAC, COPE and Hope Inc. in advance for treating patients, then the agencies would either bill for the full amount or refund what they didnтt spend. CPSA would, at times, have to return millions of dollars in taxpayer money.

Cenpatico flipped the system around. It contracts with the agencies to provide a certain amount of services per month. If the agencies donтt bill for at least 75 percent of that amount, they donтt get paid at all. at many agencies as the screws tightened and workersт days became increasingly occupied with documenting what they are doing.

тFrom the provider side, people are freaked out, because theyтre withholding payments if you donтt make your contract,т said Heather McGovern, who was chief operations officer of Hope Inc. until January and is co-chair of the local Behavioral Health and Aging Council. тI think a lot of the panic and unrest that people are experiencing is being held to the contract that we all signed. Thatтs new. Thatтs something we havenтt experienced for 20 years.т

As a result of Cenpaticoтs strict accounting, тWe may lose providers who were doing good work. But I think three or four years from now, it will be much more sustainable and vibrant.т

It sounds hopeful. But then you read like my colleague Emily Bregel has been writing, documenting Cenpatico denying expensive services. She wrote most recently of Cenpatico denying payment for a 16-year-old sex offender from Pima County who is doing well at a residential center in Texas. The state Department of Child Safety, Pima County prosecutors and others are fighting the Cenpatico decision.

CEO Terry Stevens has stated her principled opposition to putting juveniles in Level 1 treatment centers like the one in Texas. Itтs a principle that conveniently meshes with the financial interest of Cenpatico, a subsidiary of the for-profit, publicly traded Centene Corp.

So I expect these outside corporations will be able to put our local health-care institutions on firmer financial footing. That in itself is a good thing. The question is whether that will mean forcing them to settle for mediocrity in service or performance.