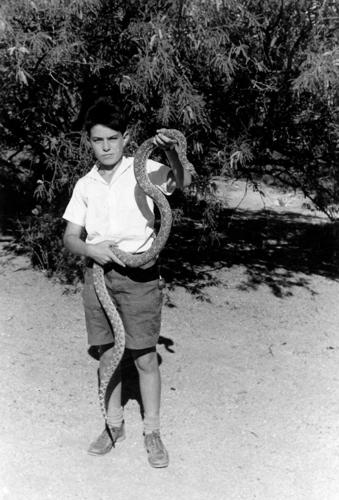

When Bill Woodin was 6, he captured a snake that gave birth to 52 offspring in a single day. At age 11, he was photographed in the Sonoran Desert near ĂŰčÖÖ±˛Ą holding a gopher snake longer than he was. At age 12, he charmed the ĂŰčÖÖ±˛Ą Rotary Club with a snake talk.

These childhood events symbolized a lifelong love affair with the desert and its wildlife that crystallized in Woodin’s tenure as executive director of the ĂŰčÖÖ±˛Ą-Sonora Desert Museum from 1954 to 1971. The museum’s second director, Woodin still has the longest tenure of any director in its 66-year history.

He played a key role in building the museum into one of the top 10 zoological museums in the United States and making it an international tourist attraction.

“He was a living legend for all of those involved in the museum,” said Craig Ivanyi, the museum’s director since 2010. “His passion and fingerprints are still there, found throughout this organization. He’s kind of into the fabric of its DNA.”

People are also reading…

Woodin died in March at age 92, at the adobe ranch house on a 40-acre parcel bisected by Sabino Creek where he had lived since the early 1950s. His second wife, Beth, a longtime conservation activist and a former Desert Museum trustee, died in January at 71. A memorial service for both will be held May 27 at the museum.

Woodin as director shaped the museum’s future as much as any individual, after its initial vision was laid down by its co-founder and first director William Carr and co-founder and financial benefactor Arthur Pack.

Carr resigned after barely two years due to ill health after the museum opened on Labor Day 1952. Woodin’s work catapulted the museum into a site whose visitors during his tenure included Eleanor Roosevelt and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor.

He inherited a facility with annual visitation of about 160,000. The year before he left, attendance had grown to 302,000. Today, the museum draws about 400,000 annual visitors.

Born William Woodin III, his introduction to the Sonoran Desert came at age 4 in 1930, when his parents moved the family to ĂŰčÖÖ±˛Ą from his native New York City. His grandfather, also named William Woodin, was President Franklin Roosevelt’s first treasury secretary, instrumental in shaping Roosevelt’s declaration of a bank holiday in 1933 that helped rescue the then-ailing financial system during the peak of the Great Depression.

William III’s father, William Woodin II, and his mother, Carolyn Hyde, had a house built along a dirt Wilmot Road near Speedway, recalled Peter Woodin, a son of the former museum director. It was one of a handful of houses existing that far east in ĂŰčÖÖ±˛Ą at the time. A neighboring home belonged to novelist Harold Bell Wright, for whom the Harold Bell Wright Estates neighborhood is now named.

Woodin’s parents were divorced in the 1930s. His mother married nationally known horse breeder Melville Haskell. They raised Woodin on a horse farm near the Rillito River near Swan Road. Haskell was a founder of the American Quarter Horse Association.

Woodin left and returned to ĂŰčÖÖ±˛Ą several times, graduating from high school in California, getting a bachelor’s in zoology at the University of ĂŰčÖÖ±˛Ą and a master’s in zoology at the University of California, Berkeley.

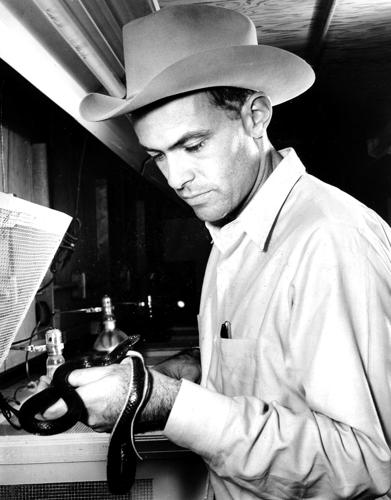

In pursuit of his master’s degree, in 1950, he identified a kingsnake species in the Huachuca Mountains, where he and his first wife, the former Ann Snow, were camped out. The species was later named after him: lampropeltis pyromelana woodini.

He started as a volunteer for the Desert Museum before it opened, and later became a staff zoologist and deputy director until taking over as director in December 1954. The museum was in a financial crisis, with benefactor Pack having pulled back his support by then. The staff had been cut to five and the museum budget was $60,000. (Its current staff and annual budget are 140 and about $9.5 million, respectively.)

Woodin embarked on a period of expansion, and introduced the museum’s first admission charge: 50 cents for adults and a quarter for kids.

Under him, the museum built an underground tunnel where visitors could see bat-roost systems, bats nesting in caves, foxes snoozing in dens and snakes nesting, wrote the Saturday Evening Post in a 1962 profile of Woodin titled, “People on the way up.” A museum exhibit called Water Street made an early pitch for saving water in the desert.

Also came exhibits and enclosures for amphibians, black bears, birds, tortoises, otters, coatimundis and other small animals, an aquarium room, artificial habitats using rocks to look like natural habitats, and a vampire bat cave. The museum’s renowned Desert Ark TV program also began under Woodin.

Woodin was always willing to allow his staff to try new things and ideas, encouraging creative people to design exhibits that were copied around the country and around the world, said Peggy Larson, the museum’s archivist.

He was called “the most promising young naturalist in the United States” by Roy Chapman Andrews, a former American Museum of Natural History director, an Asian explorer and an early Desert Museum trustee, the Saturday Evening Post article reported.

But Woodin gave the job up in 1971 on deciding “17 years was enough,” said his son Peter. He wanted to concentrate on another lifelong passion, small arms ammunition used by the U.S. military. He spent most of the rest of his life writing a three-volume history on the subject, publishing the final volume in 2015.

He also compiled “one of the great collections of ammunition in the world,” said a second son, Hugh Woodin.

He kept the collection at his Woodin Laboratory, built in 1973 and now a 3,000-square-foot underground vault, built of masonry block and reinforced concrete slabs. The laboratory, tracing the evolution of small arms ammunition, contains many thousands of specimens, many of which are the only ones of their kind, says a 2010 article about the laboratory in the publication Small Arms Review. The laboratory is a private, nonprofit foundation and educational institute. The family has kept its location private for security reasons.

In an interview in the Small Arms Review, Woodin credited his stepfather for his interest in guns. He said Haskell introduced him to shooting at an early age and “instilled in me a real respect for guns and gun safety.

“To this day, I get the creeps when someone points anything at me, even a finger,” Woodin told the interviewer.

He also compulsively collected snakes for most of his life, at one time simultaneously owning a green rock rattlesnake and two large kingsnakes. He often prowled around the desert at night with a flashlight, stick and burlap bag, searching for specimens, and kept bobcats at his home as a hobby.

Woodin used to keep his favorite snakes inside sacks in the living room until his wife Ann domesticated him, the Saturday Evening Post article said.

“It was a terrible sight when the sacks wandered around at night,” said Ann Woodin, who also forbade her four sons from bringing snakes to the dinner table. Ann, an author, naturalist and community volunteer and activist, died in 2017 at age 90.

Woodin is survived by four sons: Peter, a lawyer and full-time mediator in New York City; Hugh, a professor of philosophy and mathematics at Harvard University; John, a contractor in ĂŰčÖÖ±˛Ą; and Michael, a painter and photographer in ĂŰčÖÖ±˛Ą. He also had eight grandchildren and a great-grandchild.