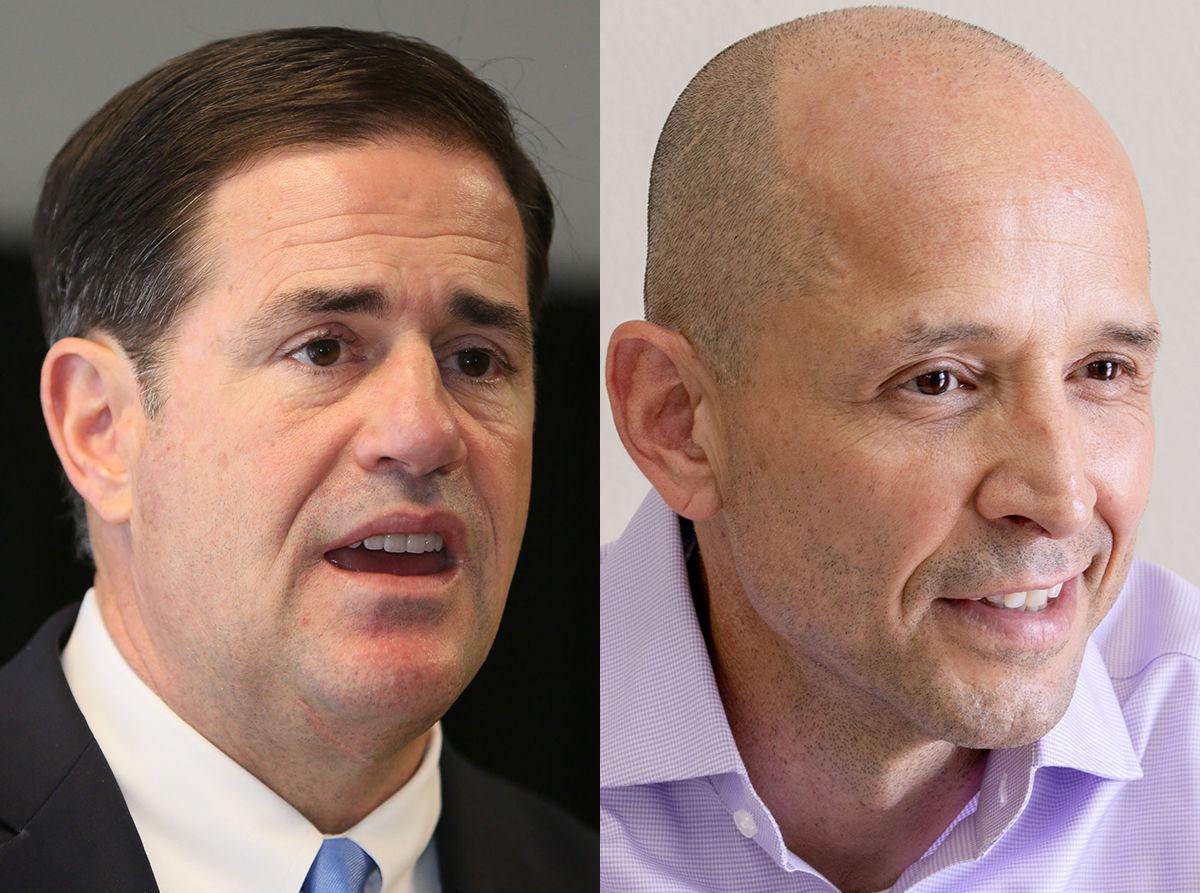

PHOENIX т УлшжжБВЅ's Republican Gov. Doug Ducey is burying his Democratic rival in a landslide of dollars.

New campaign finance reports show that at the end of September т the latest reporting period т Duceyтs campaign had spent $2.4 million on his re-election effort.

Thatтs nearly double what Democrat David Garcia spent on his effort to unseat Ducey.

But there are many more dollars out there.

Ducey reported he still had an additional $3.5 million to use on his own behalf.

And that pales in comparison with the $8.8 million the Republican Governors Association, which can take corporate dollars, is spending on attack ads against Garcia.

And, aside from his regular campaign finance committee, the governor also has a separate Ducey Victory Fund Committee. Nearly $3 million raised under that banner has been transferred to the main campaign committee and is included in the more than $5.6 million listed in contributions.

People are also reading…

More than $4 million in additional funds collected under Duceyтs name has been transferred to the УлшжжБВЅ Republican Party. Some of that comes from donors who already had given the maximum $5,100 apiece they could donate directly to Ducey.

But the state GOPтs own campaign finance reports do not disclose how much of the money they collected, including what they got from the victory fund, has been spent on Duceyтs behalf.

So why the two separate groups? The answer is simple: More money т and from more donors.

This arrangement does more than allow individuals to contribute more than the $5,100 cap. The second committee also can take corporate dollars and in unlimited amounts, something off limits to candidates but allowable in donations to political parties.

Ducey press aide Daniel Scarpinato said thereтs nothing wrong with Ducey raising money for not just himself but also for the party.

тThe governor sees a strong Republican Party as critical toward success at the ballot, both for him and other candidates,т said Scarpinato, adding that this arrangement simply gives donors тthe opportunity to provide dollars to the party.т

There is nothing that precludes any of these donors from giving directly to the party, without running it through a committee linked to Ducey. Scarpinato denied that the system was set up so that major donors could curry favor with the governor by making large donations, more than they could give directly to him.

Anyway, he said, the list of donors is public.

There are some large ones. Scottsdale-based Services Group of America has put in $250,000, with an additional $200,000 coming from the owners of Turf Paradise racetrack.

And then thereтs $500,000 from something called Blue Magnolia Investments, a limited liability company set up six months ago in Delaware which, until now, was known only for its $100,000 donation to a group set up to help the U.S. Senate candidacy of Republican Martha McSally.

Garcia appears to be getting no financial help from the Democratic Governors Association.

But California billionaire Tom Steyer, who has put millions into efforts to impeach President Trump and is weighing his own presidential candidacy in 2020, has put more than $545,000 into trying to get Garcia elected.

The issue of tracking money isnтt limited to the governorтs race.

attorney general

On paper, Republican Attorney General Mark Brnovich has collected more than $928,000 in his reelection bid, having spent about $668,000 so far.

That compares with $729,464 in donations to his opponent, Democrat January Contreras, and her campaign expenses of $308,244.

But a group called УлшжжБВЅ For Freedom has so far spent more than $1.2 million both in commercials promoting Brnovich and those attacking Contreras. The group actually is set up by the Republican Attorneys General Association which, like the governorsт group, can take corporate donations.

Contreras, by contrast, has not benefited nearly as much from the Democratic Attorneys General Association, which lists less than $8,000 in expenses here.

She is, however, at least the indirect beneficiary of a $3.6 million anti-Brnovich campaign being financed by Steyer.

Steyer is upset with Brnovich for changes that the attorney general made in the ballot description of Proposition 127, the renewable-energy mandate.

secretary of state

In the race for secretary of state, Republican Steve Gaynor continues to pour more of his own money into the campaign.

The most recent reports show he has loaned $1.9 million to his campaign. That includes money he spent on the GOP primary election to defeat incumbent Michele Reagan, and now in his general election effort against Democrat Katie Hobbs.

Hobbs, who had no primary foe, lists contributions of $782,312 and expenses of $371,805. But she also has been the beneficiary of about $2.2 million in TV commercials bought on her behalf by the УлшжжБВЅ Democratic Party.

state treasurer

There also are family loans at work in the treasurerтs race, where Republican Kimberly Yee initially borrowed $400,000 but, with additional funds since collected from others, managed to repay half of that.

So far her expenses total slightly more than $225,000.

Democrat Mark Manoil is waging his campaign largely with nearly $271,000 of public funds, having used almost $162,000 of that as of the campaign filing.

Corporation Commission

In the race for the two seats available on the УлшжжБВЅ Corporation Commission, Republican Justin Olson has spent more than $144,000 in his bid to keep the seat to which he was appointed last year.

Fellow Republican Rodney Glassman has spent more than $448,000 in his bid to be elected to the utility regulatory panel but has more than $318,000 on hand for last-minute campaigning, including $200,000 of his own cash.

Democrats Sandra Kennedy and Kiana Sears each are running with about $271,000 in public funds. The Democratsт efforts also are being advanced by Steyer, who has put $250,000 into their combined campaign.

One wild card could be УлшжжБВЅns for Sustainable Energy, a political action committee set up by Pinnacle West Capital Corp., the parent company of УлшжжБВЅ Public Service. It has nearly $2.6 million sitting on hand that could be used to help the utility elect candidates of its choice.