Remember when you made a personal discovery, one that set you on your life’s journey, filled with passion?

I’d like to think that many people have. But I suspect few have.

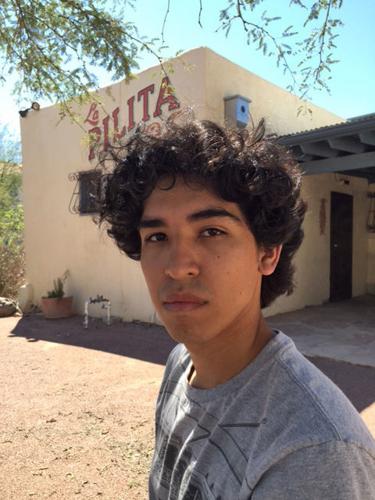

Enrique GarcĂa Naranjo, a 20-year-old Pima Community College student, encountered his and has embarked on his road.

It was just a few years ago when GarcĂa was a student at Pueblo Magnet High School that he connected with words. Poetry, to be precise.

He heard two local slam poets give a presentation after school and the power of their words, the images they created, and the rhythm and cadence, left GarcĂa mesmerized.

“I want to do this,” he said while sitting at La Pilita, in Barrio El Hoyo on South Main Avenue, on Thursday.

Poetry, he discovered, possesses special powers.

People are also reading…

“Youth individually feel like the world’s against them. But as a unit, like always, la comunidad, bringing youth together empowers them. They see that they are not alone,” he said.

The road that leads to words and writing is different for every writer. GarcĂa began his with his family as they traveled across several states and into Mexico.

He was born in Salt Lake City, Utah, where his Mexican-born parents had migrated to work. His parents came to the United States without legal permission. But his father, the son of a bracero worker, received legal residency under President Reagan’s 1986 amnesty program.

From Utah the family moved north to Idaho where there were fewer people who looked and talked like his family, which was one of the very few Mexican families.

But when he was 13, his family had to make a major move. They left for Juárez, MĂ©xico, where his mother could make her application for legal residency. Told there would be a long wait, GarcĂa moved to Jalisco, the Mexican state where his parents were born and where the young GarcĂa was a foreigner.

In school, GarcĂa helped teach English while he improved his Spanish. He also saw the effect of global trade policies and practices that destroyed small Mexican farmers, forcing them to migrate north, like his family had done.

Within a year his mother received her residency card and the family came to ĂŰčÖÖ±˛Ą in 2009. He enrolled at Pueblo and poetry came to him though the slam poetry of Sarah Gonzales and Logan Phillips, co-directors of Spoken Futures and organizers of the ĂŰčÖÖ±˛Ą Youth Poetry Slam.

With poetry came political awareness. By the time GarcĂa graduated in 2013, the state Legislature had banned Mexican American Studies in the ĂŰčÖÖ±˛Ą Unified School District. He had become active in supporting the program, which was designed to provide critical thinking skills and to teach Chicano history and culture.

Now GarcĂa is channeling his experiences and knowledge into poetry and acting.

Last month he played the role of “Poder” in “Más,” presented by Borderlands Theater. Written by Milta Ortiz and directed by Marc David Pinate, the play encompasses the development and demise of TUSD’s Mexican-American Studies. GarcĂa played the roles of two male high school students with UNIDOS, the youth group that galvanized much of the public support for the program.

The play, he said, helped him heal from the pain of what he believes was the state’s abusive hand in eliminating Mexican American Studies, a program that resulted in higher academic progress for students.

“Our history in ĂŰčÖÖ±˛Ą is full of hurt and pain. So this play reiterates that idea of resiliency and resistance,” said GarcĂa.

He has performed successfully in slam poetry recitals, participated in the Brave New Voices International Youth Poetry Festival in New York City, and won the National Association for Bilingual Education Essay Award and La Zona de Promesa Promising Leader Award in 2013.

Last year he published a book, “Tortoise Boy Says,” a collection of poems about his familia, the barrios, immigration raids, summer rain.

He shares his poetry with other young people in after-school programs, hoping to inspire, as he was inspired at Pueblo when he sat in the classroom of former Mexican American Studies teacher Sally Rusk. He believes that through poetry young Chicanos and Chicanas can express their experiences, fill in the missing parts left out of the historical narrative and make profound personal changes.

Poetry has the power, he said.

“It can open them up to this universe of literacy achievement in our culture.”

Ernesto “Neto” Portillo Jr. is editor of La Estrella de Tucsón. Contact him at netopjr@tucson.com or at 573-4187. On Twitter: @netopjr