Cannon Winkler was ready to start climbing the corporate ladder when he graduated from the University of УлшжжБВЅ with a double major in business management and entrepreneurship in 2019.

He had no idea at the time he would soon be answering a different calling halfway around the world, making pieces of art from wildlife tracks in support of animal conservation efforts.

Winkler, who now live in Sedona, creates large-scale abstract paintings using molds of wild animal prints that he collected while training to be a field guide in South Africa in 2020.

He sells the works under the name тWalks of Lifeт and donates part of the proceeds to African Parks Network, a South African nonprofit focused on anti-poaching and animal rehabilitation in the country.

тIn terms of conservation, I think I was kind of born with that connection to wildlife,т Winkler said. тI just didnтt know how I was going to help until I figured out тWalks of Life.тт

People are also reading…

Winkler had only been out of the UA a short time before he realized that business was a path, not a passion.

He wanted to do something more meaningful with his life, something that would feed his spirit and make his efforts worthwhile.

For Winkler, that meant working with animals.

тI think thereтs home videos of me when Iтm in kindergarten saying Iтm going to grow up to be a zoologist,т Winkler said.

Winkler skipped more traditional forms of animal care, looking after dogs and cats, and instead found himself on a flight to the Limpopo province in the Bushveld woodlands of South Africa, to work with larger creatures, such as lions and rhinos, buffalo and giraffes.

Winkler attended a program while there, that helped him receive official Field Guides Association of Southern Africa (FGASA) training.

тThat was a good way to get my feet on the ground and learn some useful field skills,т he said.

He wasnтt there long before COVID-19 arrived in South Africa. The country ordered residents to quarantine in their homes, which meant Winkler and his colleagues were grounded at the training camp for months.

The extended time allowed Winkler to work on his guide training, but also hone his artistic side.

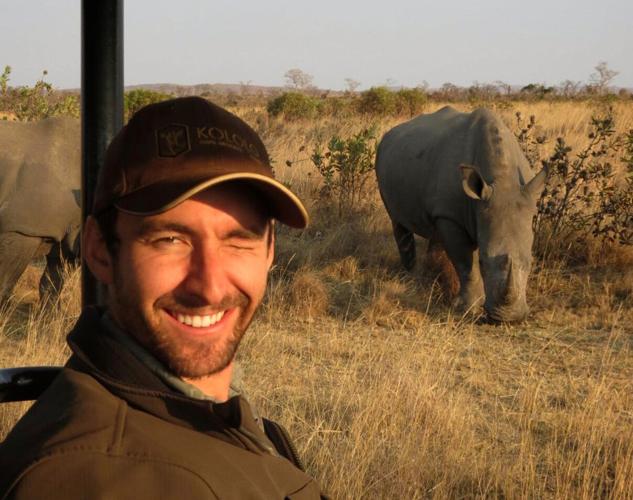

Cannon Winkler, seen here in front of a rhino, traveled to South Africa to train as a guide shortly after graduating from the University of УлшжжБВЅ in 2019.

Winkler began experimenting with making molds of wildlife tracks that he found near his camp using silicone, then arranging those tracks on a canvas in divergent patterns.

тThe idea is that everything on the canvas actually comes from a real animal,т Winkler said. тThe lion print you see comes from a lion that is still alive in Africa today.т

Winkler compares his process to that of a taxidermist, but тitтs just a lot more eco-friendly,т he said.

тEntry | Nghenaт by Cannon Winkler

Before Winkler made track molds, he had to find them first. At night, heтd listen from his bed in camp for nearby animal sounds, which gave him insight into the patterns of different animals and the paths that they regularly traveled.

In the morning, he would look for the tracks the animals left behind the night before or even days earlier.

Safety was always a concern. He was, after all, walking among potential predators.

тOnce you learn what to listen for, what to avoid, and how to act, you can move around with some level of safety,т he said.

Winkler said he sometimes followed the tracks to a point where the impression was more pronounced, such as in mud or clay. Once he was satisfied that he had found the best impression, he would inject silicone into the print and wait 24 hours for it to harden, covering the mold to prevent other animals from stepping on it.

тWildebeests like to step on them,т Winkler said. тI donтt know why but Iтve had a lot of tracks ruined by wildebeests.т

The prints would then be transferred to canvas using acrylic paint.

Winkler likens his art to тthings like cave, aboriginal dream, Bushmen rock paintings, Eastern Mandalas,т he said.

тFor me and my art, I try to express something that is very wild, but at the same time universally human,т Winkler explained. тI think with a lot of those ancient art forms you get that sense of something very primal, yet we can relate to it.т

тInhale | Hefemulaт by Cannon Winkler

Winklerтs colleague Thomas Wilson, who oversees management of the Kololo Game Reserve in South Africa where Winkler worked for six months after his initial training, said he had never heard of anyone making art from wildlife tracks.

тI got goosebumps,т Wilson said. тI just didnтt know how it was going to play out or how he was going to implement it. The basic concept of it, I found absolutely exhilarating because Iтd never seen it before.т

Marine biologist Jennifer Palmer, who also worked with Winkler at the reserve, struggled to understand what he was going for when he first brought up the idea. But she said she knew it would be something special after going with him to collect tracks.

тIt took a bit for me to understand fully what he was doing so it was kind of fun to watch the whole experience unfold,т Palmer said. тOnce I realized what he was creating and how unique this story was becoming, I got really excited.т

Cannon Winkler with his piece, тGate | Heke Iт

As far as Winkler knows, no one has attempted to create art using wild animal tracks.

Once South Africa lifted its lockdown restrictions last year, Wilson left the country and returned home to УлшжжБВЅ, where he arranged for a display of his тWalks of Lifeт paintings at Jarrodтs Coffee, Tea and Gallery in Mesa. He is currently scouting for a gallery space in УлшжжБВЅ, he said.

Winkler said he plans to return to Africa in 2022 to collect tracks from a different ecosystem for the second series. After that, he is aiming for the jungles of central Africa to track gorillas, okapi, forest elephants and other animals.

тThe long-term plan is to do a painting series from a different ecosystem each year,т Winkler said.