After the week we just had, some of us could really use a drink.

Apparently, the residents of territorial УлшжжБВЅ were no different.

Well over 200 saloons came and went in the Old Pueblo during the half-century leading up to statehood in 1912 and statewide prohibition in 1915, according to a new book on the subject.

At the peak of the early booze business, sometime around 1890, УлшжжБВЅ was home to more than 30 drinking establishments, serving a population of fewer than 8,000 residents.

тThe reason there were so many bars in УлшжжБВЅ is there werenтt a lot of things to do for single men,т said Homer Thiel, a historical archaeologist with the УлшжжБВЅ-based consulting firm Desert Archaeology.

People are also reading…

Thiel has just authored a comprehensive history of local watering holes during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. тTerritorial Saloons of УлшжжБВЅт spans the period from March 1856, when the Mexican military withdrew from post-Gadsden Purchase УлшжжБВЅ, to Jan. 1, 1915, the start of the stateтs 18-year ban on alcohol.

Historical archaeologist Homer Thiel leans on the bar next to a late-19th-century liquor bottle at Hotel Congress in УлшжжБВЅ on Thursday. Thiel just published a comprehensive history of territorial saloons in УлшжжБВЅ between 1856 and 1915.

Thiel uses census records, newspaper accounts and other source material from that time to chronicle 247 different saloons.

He said none of those businesses survived Prohibition, and the buildings that once housed them are long gone, too т lost to newer construction and urban renewal in what is now downtown УлшжжБВЅ.

Digging for clues

The idea for the book sprang from a 2005 archaeological dig Thiel took part in at , which operated from 1884 to 1910 across Toole Avenue from the Southern Pacific Railroad depot.

The city of УлшжжБВЅ hired Desert Archaeology to excavate the property before an underground parking garage was built there. But it wasnтt exactly glamorous work. Nearly all of the historic clues Thiel and company found were unearthed from outhouse pits where the saloon and its customers used to dump their trash more than a century ago.

Artifacts included various alcoholic beverage bottles, shot glasses, beer steins, fragments of an embossed Anheuser-Busch mirror and pieces of window glass with hand-painted lettering that once spelled words like тfoodт and тsaloon.т

Based on makerтs marks and the types of glass used, most of the items tossed in the trash pits dated to between the 1880s and early 1900s.

Thiel said the Cactus Saloon was one of several positioned near the tracks to take advantage of the arrival of the railroad in 1880. People passing through town could get off the train to get a meal, a haircut or a drink before returning to the station.

Old photos of the Cactus show a jaguar pelt draped over a picture hanging above the bar. Apparently, customers could also have their shoes shined there, Thiel said, тbecause we found lots of shoe-shine bottles.т

Bartenders pose for a photo, circa 1900, at the Cactus Saloon, which operated until 1910 across Toole Avenue from the Southern Pacific Railroad depot in УлшжжБВЅ.

To help inform the archaeological dig, he poured over microfilm of old УлшжжБВЅ newspapers to learn more about the Cactus Saloon and other establishments from territorial times.

He started to expand on that research years later during the COVID-19 pandemic, when he was stuck at home and looking for something to do. тYou can only put together so many puzzles,т Thiel said.

Boom and backlash

The resulting book features a detailed look at what saloons of the era looked like and a short history of alcohol consumption in УлшжжБВЅ, from Oтodham ceremonial wine made with the fermented syrup of saguaro fruit to the sacramental wine kept by Catholic priests and the bottles of liquor hoarded by soldiers at the Presidio.

The book also includes biographies of 74 saloon proprietors and employees whose stories Thiel was able to piece together from public records, newspaper archives and at least one surviving diary.

The 1860 federal census counted just two brewers and no saloonkeepers or bartenders in УлшжжБВЅ. The first evidence Thiel can find of a saloon operating here comes in the form of an 1865 ledger from proprietor Solomon Warner, who reported charging 25 cents for a drink or a cigar, 50 cents for a game of billiards, and between $3 and $6 for a bottle of liquor or champagne.

By 1869, a few other УлшжжБВЅ saloons had begun to advertise in newspaper.

Any type of alcohol that wasnтt made here had to be brought in on freight wagons until 1880, when the arrival of the railroad made life far easier for saloon operators.

City directory listings from 1883 show 54 УлшжжБВЅans employed at saloons or in other liquor industry jobs. According to Thiel, that number increased to 66 in 1897 and topped out at 164 in 1899.

As the bar business grew more competitive, establishments sought to lure in customers by offering free food with the purchase of a beer or other drink. At Thanksgiving, some places would give away a whole dinner with all the fixings in hopes of selling more drinks, Thiel said.

Meanwhile, a backlash was building. Starting in the late 1870s, some civic leaders began trying to rein in УлшжжБВЅтs saloon culture and tame the communityтs rough-and-tumble image. New ordinances were gradually enacted restricting hours of operation, barring loitering and alcohol consumption by children under the age of 16 and outlawing gambling and prostitution at drinking establishments. Saloons were even prohibited from staging musical performances featuring women.

Eventually, under the guise of widening Congress Street, the city razed the bars and brothels in an area known as the Wedge, at the present-day location of , home of УлшжжБВЅтs infamous Pancho Villa statue.

But enforcement of the new rules proved to be disturbingly selective at times, Thiel said. In the early 1900s, for example, authorities conducted frequent raids at the Arcade Social Club, an unlicensed drinking establishment that was for a time the only club in УлшжжБВЅ catering almost exclusively to Black people.

End of an era

The growing temperance movement in the young state of УлшжжБВЅ ultimately led to aimed at prohibiting alcohol statewide. Though Pima County voters soundly rejected the measure, it passed anyway thanks to heavy support in т you guessed it т Maricopa County.

Several local saloons marked their final hours in a тwetт jurisdiction with elaborate farewell parties on Dec. 31, 1914. According to a report in the УлшжжБВЅ Citizen, a restaurant and bar called Rossiтs at the corner of Congress and Stone Avenue brought in cabaret dancers from San Francisco to perform while the patrons drank the place dry.

That was the last day alcohol could be legally sold in УлшжжБВЅ, so thatтs where Thielтs historical pub crawl ends.

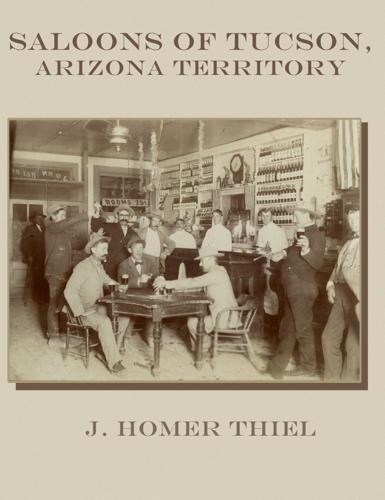

The cover of Homer Thielтs new book on the Old Puebloтs old saloons.

But as extensive as his 374-page volume is, he said dozens of territorial-era drinking establishments did not make it into the book т places largely lost to history because they were overlooked in their own time by the communityтs English-language newspapers of the day.

тI am really interested in the Mexican-owned bars,т Thiel said, but there doesnтt seem to be much surviving documentation of them.

Some evidence suggests there might have been just as many cantinas operating in Barrio Libre as there were white-owned saloons elsewhere in УлшжжБВЅ. All Thiel could find, though, were brief references to such businesses in a few surviving Spanish-language newspaper clippings.

тThis is as much as I could possibly do,т he said.

УлшжжБВЅ Landmarks: Hotel Congress, 311 E. Congress St., opened in 1919 as a luxurious mainstay for visitors arriving in the Old Pueblo.

The downtown landmark has kept much of its history alive in the past century, while also bringing modern amenities to УлшжжБВЅ natives and tourists.

Video by Riley Brown / For the УлшжжБВЅ