They are dying by the hundreds, 372 on average тІ every single day.

Their numbers were once in the millions, an estimated 16 million plus. In 2016, there were only 620,000.

It was т and is т the greatest call to arms in the history of the United States, according to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

Some were young men and women, the flowers of their generation, who answered the call when their country asked for their help.

They are World War II veterans, part of what has been named the Greatest Generation.

Simple everyday citizens, like B-17 co-pilot Charles Gutekunst and WAVE Helen Glass, a poet who repaired engines on fighter planes, have left their indelible mark.

Others, like George McGee and Richard Kassander, died this summer, but their memory and stories live on.

People are also reading…

Next week on Veterans Day, we honor these and all veterans on the anniversary of the end of World War I, optimistically called тthe war to end all wars.т

However, their experiences and legacies, as well as those veterans from other eras, are at risk of fading away being forgotten forever unless a conscious effort is made to document their stories.

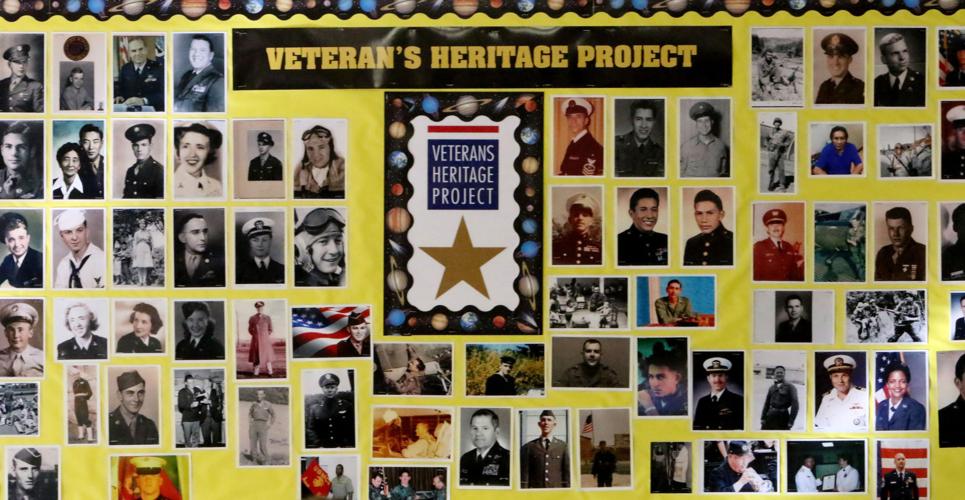

University High School teacher Don Dickinson has been involved in the Veterans Heritage Project since the start of the 2013-2014 school year. Students meet in class and as a lunchtime club to honor veterans, capture their stories and give them the respect they deserve.

Vietnam veteran David Powell gives veterans a respectful farewell and a final salute through his work with the We Honor Veterans program.

In their own way, they are making every effort to emulate the military creed: No one left behind.

Veterans Heritage Project

The Veterans Heritage Project closely mirrors, but is not part of the Veterans History Project associated with the Library of Congress, which also collects and preserves the personal accounts of veterans.

тWhat I am trying to do here is to work with my students to be historians,т Dickinson said adding, тIn particular, I want them to preserve the oral history of our veterans who probably wonтt be here in a few years.т

Veterans are interviewed in class, where they are videotaped as they reflect on their military experiences. The project allows students to learn history directly from them and maybe have a better understanding of our military in times of war and peace.

Dickinson, 73, said veterans are videotaped and the transcripts are turned into stories and made into a book that is then given to the veterans.

The videos are then forwarded to the Library of Congress for their archives to preserve the oral and written history of veterans in military conflicts, Dickinson said.

тIt is a really popular class,т Dickinson said. Even though the class is limited to only 32 students, some 190 students signed up for it. The club has 50 additional students that meet every other week at lunch, he said.

тI feel as a teacher, I am opening a door to an important part of my studentsт heritage,т Dickinson said.

In addition to developing their writing skills, there is also an opportunity to perfect their communication skills. They not only talk to veterans, they have to speak in front of their classmates, some of whom will also be selected to talk in front of the whole school during their end-of-the-year assembly.

Junior Tatum Boldt, 16, and senior Ryan Sheets, 18, are two students taking the class.

тIтve wanted to take this class since I first heard about it,т Boldt said. тI come from a military family.т

Her grandfather served during the Vietnam era, she said. тHeтs been telling me about his military experiences as far as I can remember.т

тItтs really important to learn from our past so we can prepare for our future,т Boldt said.

The focus of the class is on military history, and it is good to comprehend American history in its entirety, she said.

The veterans want us to learn from them but also, тto be able to have respect and be grateful for what they have done for our country and for us,т she said.

Sheets added that most history classes teach about the тwhatтsт of history as in тwhatт happened.

In class you learn how it affected people т thatтs where history really comes to life, he said.

Their personal details are foreign, hard to imagine. They are from a different time and a different world but their stories become real, Sheets said.

тI have gained so much respect for the men and women who have served and their sacrifices they had to make.т

A veteran reminded Sheets that he is free and not to waste the gift of freedom. тI think about that a lot. I think about the opportunities both daily and those down the road.т

Instructor Dickinson said the class gives his students empathy and provides a reality check to keep their own problems in perspective.

But there is also a personal element to all of Dickinsonтs efforts. For him, he is passionate about the project because of a man he never met.

His father, 2nd Lt. James Franklin Dickinson, was a reservist who was attached to Pattonтs Third Army. He was riding in a lightly armored vehicle on a reconnaissance mission when he was killed in Braunau am Inn, Austria, Adolf Hitlerтs birthplace, in the last days of the war.

тMy father was killed May 4, 1945, the day before the Germans surrendered in Austria,т said Dickinson,

Four days later it was May 8, 1945, V-E day, and end of the war in Europe.

Years later, he came across memorabilia that his grandmother had collected on his father and that family members had kept.

тMy grandmother had saved all my fatherтs report cards, sports clippings, photos and letters,т he said.

тI spent almost a year putting all that together. Thatтs when I got to know my father тІ at age 50.т

His mother remarried, and his stepfather, Robert Anderson, was an Army pilot who flew in the Pacific who was called back for the Korean War but was killed during a night training mission.

His second stepfather, Robert Paine, was captured during the Battle of the Bulge and held as a prisoner of war. тI remember growing up he had PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder). But he was the one who raised us. He stepped up and helped put our family together.т

тThis project, for me personally, is about honoring all my fathers.т

Veterans have expressed concern to Dickinson, feeling todayтs youth are not patriotic.

тIf they are perceived as such,т Dickinson said, тitтs not their fault.

тOnce they learn of the sacrifice, they become the veteranтs advocate and they feel the sense of sacrifice. It is personal, itтs human and they become patriotic.т

тSafe comfort zoneт

David Powell became an eyewitness to war while in Vietnam, and it played a big part in forming his current life. The experience, coupled with other events, including caring for his dying mother, has now led him to comfort fellow veterans in their final days.

Through the organization, We Honor Veterans, he honors them by listening to their stories, giving them comfort, praying at their side and, at times, standing vigil over them.

тIt was my spiritual upbringing that had to do with my being more aware of people that are hurting or are in crisis,т he said.

Born in Chicago but raised in УлшжжБВЅ for his health, Powell graduated from Amphitheater High School in 1968.

Even as a youth, Powellтs family considered him a spiritual person: тMy parents wanted me to become a chaplainтs assistant.т

The U.S. Army, in its characteristic way, had other plans for him.

Drafted in 1969, Powell found himself with the 4th Army refueling helicopters around Vinh Long Airbase in the Mekong Delta.

Powell arrived in the country around the time of the 1969 Tet attacks involving North Vietnamese and Viet Cong assaults in the Saigon area and in Da Nang, farther north.

When Powell returned to УлшжжБВЅ, he found himself working for his fatherтs business, Canyon State Industries, which at the time provided sanitation supplies throughout УлшжжБВЅ, including all the Native American lands.

тMy travels, especially on Native American reservations, opened my eyes to the relationship between the different cultures,т Powell said. Many Native Americans are into honoring their veterans in any fashion. They are very proud of them and he came to appreciate how they were treated.

тIt was heartwarming to experience their memorial services,т he said.

He quit his business in 2012 after caring for his mother, Betty, at her home the last 10 days of her life. He managed her medications and made her life as comfortable as he could. It was then she told him, тYou missed your calling.т

тThat statement changed my life,т he said.

Powell took an online divinity course through the University of Dubuque Theological Seminary for two years, graduating in 2015.

He became a commissioned lay pastoral minister through St. Albanтs Episcopal Church and started to work with УлшжжБВЅ Medical Center Hospice as well as all the hospitals in УлшжжБВЅ and Southern УлшжжБВЅ.

Powell, now 68, first began working with We Honor Veterans in 2014 and volunteered as a former military person who wanted to honor vets at TMC Hospice.

We Honor Veterans is a program under the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization and works in conjunction with the Department of Veterans Affairs.

It provides an avenue where Powell can help veterans toward a more respectful and peaceful end to life.

On his arrival, тI show up in my uniform and have a plaque made ready for them with their name.т

It helps them that he always wears his olive drab military flight suit.

тThey always start talking about their service when I arrive in uniform. Itтs almost like I provide a safe comfort zone for them to talk.т

The plaque acknowledges the military branch in which the veteran served, and it has the inscription: тWe thank you for your service, for serving America and for advancing the universal hope of freedom and liberty for all.т

He also places an American flag in the room or on a stand next to their bed. They receive a hatpin that shows their military branch т it is something the veterans really like the most, Powell said.

The spouse also receives a pin, which is an American flag in the shape of heart, and they are honored for caring for the veteran through the years.

Then, he gathers as many other veterans as he can at the facility and together they give the dying veteran a final salute.

He often works with WWII veterans and has had as many as eight honor ceremonies in one week. They make up for about half of his visits, he said.

It is not uncommon that they tell him they donтt deserve any recognition, but he usually tells them, тRespectfully, sir, if I can speak for myself and all Americans, we enjoy our freedoms every day because of people like you who have honorably served your country.т

He feels fortunate to hear their stories.

тItтs because of them I enjoy many freedoms. I enjoy them because of their sacrifice.т

Helen Anderson Glass

(Born March 8, 1923.)

Helen Anderson Glass has lived through some interesting times, and sheтd be the first to tell you.

Sheтd also be the first to tell you she danced with Frank Sinatra in 1940 at Frank Daileyтs Meadowbrook, a famous dance hall featuring some of the best big-band musical groups of the time in her native New Jersey.

тOnly,т she said pausing briefly, тI really didnтt dance with him personally. We were on the same dance floor at the same time.т

Like many from her generation, she lived through the Great Depression, was a veteran of a World War, watched men land on the moon and has seen computers do some remarkable things.

тIтve lived through so much history, itтs annoying,т she saidwith a bright smile and a chuckle. While she talks she is surrounded by colorful tote bags and lap robes bearing the logo of all the different military branches.

Some time ago Glass, 94, noticed some veterans shivering in their wheelchairs at the local VA hospital so she created a lap robe that fits over them so they can keep warm. Each has a separate military logo for the various branches: Army, Navy, Air Force, Marines and Coast Guard with a space for a note pad, pens, even a cellphone.

She has made bags for those needing walkers, busy aprons for vets with PTSD and lap robes for veterans т and those are only some of the ways she continues to serve her country.

тThis is therapy for me,т she said.

Itтs also her thing, a tradition that started with her father, Arthur, who was gassed, wounded and shell-shocked and who suffered from a broken blood vessel in his heart т his injuries from the тwar to end all wars.т

тIтve been doing it since I was young when Iтd visit my father in VA hospitals in Florida. Iтd read to vets, push their wheelchairs into the sun so they could get warm and listen to their stories.т

Even though Glass is outgoing, friendly and anxious to help them, she is quite modest regarding her contribution during World War II.

At the start of the war, her brother Arthur Anderson, who joined the Navy when the war began, persuaded her to join the WAVES, or Women Accepted for Voluntary Emergency Services, which was part of the Naval Reserves.

The purpose of the WAVES was to take over some duties from officers and men so they would be available to go to sea.

Now, Glass says, тWe didnтt release a man to go to sea, we made our place in history.т

But when she went down to the recruiting station, she was shocked because they would not accept her. She was not old enough, so she would have to wait until she turned 20.

тIf I had a college education, they would have taken me right away.т

She was accepted into the WAVES on her 20th birthday and became an aviation machinist, which was not too surprising considering she came from a long line of auto mechanics and electricians, including her father and brother.

тI came by mechanic work naturally,т she said.тI used to help my brother work on his cars, set the plugs, change the oil, do the lubrication, coolant, battery, tires, the works.т

In the WAVES, Glass worked on the engines of several of the most recognizable fighter planes of the era, the F4U Corsair, the F4F Wildcat and the F6F Hellcat.

She was trained to troubleshoot engine problems. тWe had to make sure everything in the engine was working right. The engine had to be really clean because when they would bring them in they were messy and dirty and we had to overhaul them.т

Glass recalls at one point it was determined the engine on one of the planes came with a defective part. The oil pump came with inferior copper wiring that caused a hex nut to shear off and the engine would fail, sometimes with deadly consequences.

тSome men resented us because we were getting ratings (going up in rank) over them because we took our jobs seriously by working hard and studying more, and then weтd follow on our training. Other than that, they were wonderful.т

In 1944, she was scheduled to work in Hawaii, which was the only overseas station where the Navy would let WAVES serve, but Glass was informed her brother was missing in action and her father was in serious condition at a VA hospital. As a result, she remained stateside.

While on leave, the family was informed that her brother was killed off the coast of Italy when his ship, the USS Savannah, came under attack by a Nazi radio-controlled glide bomb.

After the war, she found closure by sending flowers to a memorial in Italy. She sent them on her brotherтs birthday, Veterans Day, and Memorial Day for 10 years, she said. тHe was my hero.т

Glass became an award-winning poet, using stories inspired by men and women who have served in uniform, many whom she encountered at the VA.

In an excerpt from her 2015 poem, тPeaceт she wrote:

ттІPeace begins with you and with me

And it should start right now

With each of us being willing to change

And take a solemn vow

To put politics behind us and uppermost

Be a loyal citizen of the U.S.A.

Our time is running out. There is none left

We must do it now. This very day!...т

In the end, it is her wish that people see Veterans Day and Memorial Day as more than just another day off.

тTake an interest in a homeless veteran, go to a veteranтs home or a hospital and see patients,т she said.

It is the least that can be done.

Charles Gutekunst

(Born Feb. 18, 1919.)

While on his very first B-17 mission in Europe, Lt. Charles Gutekunst had the best seat in the house.

The trouble was, he was not in his usual co-pilotтs seat where he had trained for months.

Instead, by order of his group commander, he was situated in the tail gunner position on the commanderтs plane, where he was assigned as the formation control officer.

Since a commander flies in front of an 18-plane formation, тI can only see forward so youтve got to help me keep the group together. If anyone is out of formation or is straggling behind, you have to let me know,т Gutekunst, 98, recalled his commander telling him.

It was the early part of 1944 and Gutekunst, a native of Philadelphia, found himself flying in the U.S. Army Air Corps, with the Eighth Air Force.

He had been interested in flying since his youth, making model airplanes as a child and actually flying since his late teens.

Before the war, Gutekunst even had a plane, a Taylor Cub, the forefather of the Piper Cub, a small, light airplaneтbut when he bought it, the plane had no brakes.

When Gutekunst first enlisted in 1942, he had hoped to become a fighter pilot, flying in the cockpit of a P-38 Lightning.

However, in 1943 the Allies suffered heavy losses and the need for bomber pilots grew critical.

тThe first time I saw a B-17, I was amazed at the size from my experience with flying other military aircraft. It was a pretty powerful airplane,т he said.

Still, he found himself surprised to be in the tail gunner position on his first mission.

At one point he noticed three Nazi fighter planes attacking a B-17 in the formation and wondered to himself, тWhy isnтt anyone shooting at them?т

He could see pieces of the bomber flaking off the body of the plane as the fighters attacked. Gutekunst trained the guns from his tail gunner position and fired on the German fighters.

When another B-17 gunner started firing at the planes, two of the German fighters broke off their attack but one stayed and continued shooting at the original bomber. Gutekunst and the other gunner hit the lone Messerschmitt Bf 109 and together they drove him off. Gutekunst eventually shot down the Me-109, giving him half-credit for a kill.

тI personally know I am one of the damn few bomber pilots to ever shoot down a fighter,т Gutekunst said.

As a co-pilot, he was comfortable flying in formation although doing so was fraught with danger because of the possibility of mid-air collision.

The strategy behind the tight formation maximized the firepower of the bombers to train their gunners to interlock their machine guns on Nazi fighter planes and hopefully prevent their own craft from being shot down. Another reason for flying so close together was to maximize a tight bomb pattern when all the bombs would be released at the same time.

Even so, Nazi fighters changed tactics and attacked B-17 formations head-on because, for a time, the planes had the least amount of firepower in the front.

When encountering a head-on attack, Gutekunst recalled dropping the flaps, increasing the power and causing the nose of the plane to tilt up. тI got the nose between me and the fighters and I felt if we are going to be hit, it would hit the nose of the plane first. My theory at the time was т lose the pilot, lose the airplane.т

But that tactic did not sit well with the navigator and the bombardier who were in the nose of the bomber, he said.

At the end of the mission, тThey would chew me out for half the day.т

By early June 1944, the Allied invasion of Nazi-occupied France was forthcoming and it was only a matter of when. In the time leading up to the event, they were training to fly at night in tight formations.

Then, they were awakened early June 6 and told they were bombing coastal defenses along a beach in France.

тI remember on D-Day I saw at least three explosions,т he said, from planes that either collided or hit the ground as they were establishing their formations over England.

тI know that somewhere over England with each explosion, 20 guys died.т

On the way to the target, тIt was one of the most exciting things youтd ever seen in your life. Thousands of Navy ships down there and the big ones shooting ashore. Iтm pretty sure I saw a battleship or cruiser firing broadsides at the beach.т

It was a maximum effort by the Allies.

тI think that every B-17 that was flyable was out there.т

He flew two missions that day and after flying 11 to 12 hours, the last thought he had before falling asleep was, тI hope we did some good for those guys who are staying there tonight.т

When Gutekunst first arrived in England in February 1944, pilots and crew only had to survive 25 missions, then, they could rotate out and return home to the states. By the time he finished 23 missions, тthey changed the number to 30 missions. When I got to 28, it went to 35.т

With one mission to go, he was asked if he wanted to be in a movie that was being shot in England instead of a combat mission.

The British-made movie was called тThe Way to the Stars,т but in the U.S., the movie was released as, тJohnny in the Clouds,т according to the Internet Movie Database. But good luck in finding Gutekunst flying in the movie т he appears as a catcher during a baseball game.

After the war, he remained in the service and changed over to the newly formed U.S. Air Force, retiring as a colonel. He continued flying after his retirement and last flew in 2013, when he was 94.

As far as his role during the war, тI am under no illusion. The war will be forgotten by those who donтt remember it. тІ I am more worried about the next one.т

Sgt Richard Kassander

(Born Sept. 10, 1920-died

July 27, 2017)

Throughout his service in World War II, Richard Kassander had to live with the fact the U.S. Army gave him a score of 64, a normal to average IQ rating, after taking the Army General Classification Test. It is a test that is meant to assess intelligence or other abilities.

The real story, as told by his son-in-law Richard Ruskin, Kassander actually scored a 164 т but when an officer saw the results, he thought it was a misprint because heтd never seen a score so high.

Never mind that Kassander would eventually become a University of УлшжжБВЅ vice president or that he would become professor of physics and director of the UA Institute of Atmospheric Physics т that was years later.

By 1943, Americaтs effort to vanquish fascism was in full swing when Kassander, who was raised in New York, was drafted. Kassander had just gotten married to his beloved Sally. He became a combat engineer, trained in the fine art of demolition.

The Army discovered he had a masterтs degree and had worked as a petroleum geologist, so it did the next best thing тІ it assigned him to the 1375th Engineering Petroleum Company.

He was taught to lay gasoline pipelines, connect pumps and to operate, as well as erect, storage tanks, some of which could hold a million gallons of precious fuel.

For a modern Army with its fast-moving tanks, mechanized transports and aircraft, fuel was a vital part of the war effort. Without it, a modern army could not move.

A month after D-Day, Kassander found himself on a barge heading toward France. His unit was ordered to scramble down into a Landing Craft Tank, or LCT, that was going to Utah Beach. After the ramp dropped he waded in four-feet of water with a rifle over his head as his unit walked on French soil.

His unitтs mission was to establish a continuous line of fuel with storage tanks every 50 miles, depending on the terrain, and stay as close to the front lines with the advancing troops as best they could.

Before warтs end it had built an extensive system of pipelines and tanks across northern France, Belgium, Holland, Luxembourg and over the Rhine into Germany.

The unitтs weapons: bulldozers, tractors, jackhammers, light cranes, welding equipment, electric generators, pumps, engines and parts.

In the process, the outfit supported Gen. Omar Bradleyтs First and Pattonтs Third Army, as well as the Ninth Army. They also supported the British Second Army and the Canadian First Army.

Kassanderтs outfit participated in the breakout from Normandy, the Battle of the Bulge, as well as campaigns in the Rhineland and Central Europe.

During the Bulge, his platoon found itself behind German lines while on the way to Holland to assemble a large fuel tank near an airstrip.

Upon reaching Allied lines, the platoon was greeted by cautious GIs wary of German infiltrators dressed in American uniforms. They were allowed to pass only after a member of his outfit knew a тdeck of humpsт meant a pack of Camel cigarettes.

The outfit continued to build pipelines until the European war ended in May 1945. From there its members were to return to the States for retraining and then continue on to the war in the Pacific. That is until August, when the atomic bomb was dropped, prompting the Empire of Japan to surrender.

After his discharge he used the GI Bill to get a doctorate in physics from Iowa State University in 1950 then joined the faculty at the UA.

As a UA vice president for research, Kassander was instrumental in the creation of numerous organized research units including the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory and the Flandrau Planetarium.

Not bad for a man with an IQ of 64.

Cpl. George Wesley McGee

(born April 11, 1925-died Sept. 2, 2017)

With the warmest of тgreetings,т George W. McGee, like millions of other young American men at the time, received a letter telling him to report to the nearest induction center. For McGee, who received his letter on July 23, 1943, that meant he had to report to the City Hall in Colby, Kansas.

Three months before, he turned 18 and was still a high school student, but now his future was in the hands of the U.S. Army.

He was about to take part in the liberation of Nazi-occupied Europe that, for him, began as he waded on shore at Utah Beach in Normandy, and ended in Pilsen, Czechoslovakia, all the time with the 109th Evacuation Hospital.

Most of McGeeтs experiences with his unit were documented in the letters he sent to his mother, Mary Bayne McGee, who kept a diary of the letters he wrote to her, giving him the information to write his memoir years later.

The group, similar to a M.A.S.H. unit, operated thousands of yards away from the front lines, giving vital medical aid to soldiers as quickly as possible.

On one occasion in Normandy, the unit put their training to work by assembling the entire hospital in the dark, ready to operate at first light.

тWhen daylight came I couldnтt believe how well the hospital had been set up,т he wrote. тThe tents were almost in a straight line and all the cots and equipment was set up.т

The only trouble was they had set up тas close to the front as we have ever been.т

тIn fact, we learned later that we had been surrounded for a day by the Germans,т McGee wrote.

In Belgium, at the Battle of the Bulge, the unit treated 2,414 casualties, including members of the 101st Airborne Division, the 28th Infantry Division and the 4th Armored Division from Pattonтs Third Army.

During most of his time with the unit, he was the assistant mail clerk, who тwas either the most loved, or hated person because the mail hadnтt found them yet,т said his daughter Victoria.

While serving as the unit mail clerk, McGee was strafed by a German Stuka dive bomber near Metz, France, and encountered sniper fire around Frankfurt, Germany.

During the Battle of the Bulge, McGee inadvertently followed an Army truck that had a British insignia on it.

тWe were ticked off because they moved so slowly,т he wrote. тWe would honk but it did no good.т

After a while, the truck turned off and they were able to go around it. Down the road, Army military police stopped them and inquired if they had seen the same truck because, it turns out, it was full of German infiltrators dressed in British uniforms.

McGee witnessed the carnage of war including тa sight I wish I had never seen and will never forget.т

Near St. Mere Eglise, in Normandy, France, he witnessed тrows upon rows of bodies, covered and awaiting burial. It is an odor that stays with you forever.т

By the end of the war, the 109th Evacuation Hospital received a Meritorious Unit Citation for having the lowest death rate in the entire European Theater of Operations, less than one-half of 1 percent. They admitted, treated and evacuated 25,267 casualties.

Members of the unit also earned five battle stars.

Years later, he received the French Legion of Honor and served as president of the Southern УлшжжБВЅ Chapter of the Veterans of the Battle of the Bulge.

McGee married the love of his life, Juanita Puckett, in 1948 and they were together for 54 years. They had a family and eventually he worked for IBM as a quality engineer, retiring in 1988.

One more thing: Upon his return from fighting throughout Europe, on his way home with a fellow veteran, McGee was denied liquor while having dinner at a Kansas City hotel.

He was 20 years old.