A former University of ĂŰčÖÖ±˛Ą gymnast says the school is falling short of its duty to cover medical bills related to an eating disorder she developed while on the team.

The athletic department, meanwhile, says the condition is not covered by NCAA or school policies.

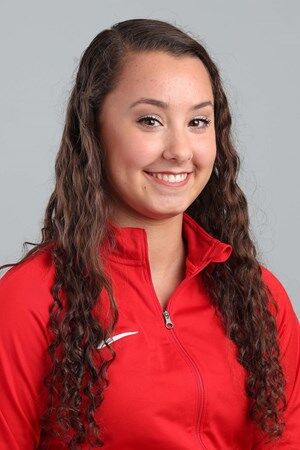

Sydney Freidin, 22, believes the UA should continue to cover her mental health expenses after graduation. Freidin, who is in treatment now, says she pays $1,200 a month for costs associated with a dietician and therapist, beyond thoseĚýher parents' insurance will cover.ĚýShe says that does not include a psychiatrist paid for by her parents.

The UA is covering surgeries and physical therapy related to Freidin's multiple hip injuries — two torn labrums that forced her to medically retire from the Gymcats in 2019. She's already had one of two required surgeries, and will undergo the second soon. Because the injuries occurred while Freidin was competing for the UA, NCAA bylaws require they pay for both, as well as 12 weeks of post-operative physical therapy.

People are also reading…

While that language is clear, there is no formal mandate when it comes to providing mental health services once a student has left his or her sport. Disordered eating is classified as a mental health issue.

The UA says it doesn't discuss details of medical treatment for student-athletes, but that the school's medical team provides "exceptional care" that often exceeds what is required by the NCAA.

Freidin, who was a walk-on, believes the university should continue paying for her care since her condition stems from her time on the team.

"I competed for them and made them money over my time there, and to not be compensated — especially when I wasn’t on an athletic scholarship — is hurtful," she said. "No one questioned the coverage of my hip surgery because you can clearly see it on an X-ray. Just because you can’t see my eating disorder on an X-ray, doesn’t mean it’s any less real. If anything, my eating disorder hurts my health so much more than my hip."

Terminating coverage

In August, a few months after graduating from the UAĚýwith a degree in nutritional sciences, Freidin received a letter from the athletic department's chief operating officer that left her floored.

"Congratulations on graduating from the University of ĂŰčÖÖ±˛Ą, it is a tremendous accomplishment!" the letter from Derek van der Merwe said. "The university will be terminating its coverage of insurance costs related to your eating disorder."

Freidin says the eating disorder was diagnosed in April 2018, at the end of her freshman season with the Gymcats. A UA doctorĚýmade the determination following a body composition test; Freidin had undergone an identical one before the start of the season, and no concerns were noted.

Born with congenital hip dysplasia, Freidin had seen plenty of doctors throughout the years and said she had never been diagnosed with disordered eating. The UA sent her to see a nutritionist for the eating disorder, something Freidin said made her condition worse. She eventually entered treatment.

The letter from van der Merwe told Freidin she would have a few months to transition to her own coverage, and that reimbursements for her weekly visits to her dietician and therapist would end on Nov. 5.

Freidin appealed the decision, writing letters to athletic director Dave Heeke and UA President Robert C. Robbins. That didn't change the UA's decision.

A common problem

Over the past decade, a number of studies have examined disordered eating in NCAA athletes.

A February 2020 research article published in The Sport Journal reported that up to 84% of collegiate athletes reported engaging in unhealthy eating and weight control behaviors, including binge eating, excessive exercise, strict dieting, fasting, self-induced vomiting and the use of weight-loss supplements.

A 1999 NCAA study of Division I athletes found that over one-third of female athletes reported attitudes and symptoms placing them at risk for anorexia. In 2015, a pair of researchers found that female athletes in so-called aesthetic sports — including gymnastics, diving and swimming — had higher degrees of body dissatisfaction or disordered eating than in other sports or in the general population, according to the Women's Sports Foundation.

Studies completed in 2001, 2004 and 2009 found that in so-called "aesthetic sports," disordered eating in female athletes occurs at estimates of up to 62%, according to the National Eating Disorder Association.

Despite the widespread nature of eating disorders, they aren't addressed directly by NCAA policy. The governing body refers to injuries and illnesses but does not specify whether they need to be physical in nature, or whether mental health-related issues are also covered.

UA officials say they can'tĚýsay much about Freidin's situation, citing student privacy laws.

"It is not our practice to discuss the details of the medical treatment our student-athletes receive," said UA spokeswoman Pam Scott. "That said, during the time that athletes are enrolled here our medical team consistently provides exceptional care to our athletes. We have full confidence in the care and thoroughness that our medical team provides to each and every athlete, care which often exceeds that required by the NCAA and the Pac-12. We strongly refute any assertions suggesting otherwise."

The UA declined to answer the Star's follow-up questions about its policy for diagnosing preexisting conditions in student-athletes or if there were any staffing changes between Freidin's first and second body composition check that could have resulted in her eating disorder not being diagnosed the first time around.

Dozens of student-athletes graduate from the UA each year, although it's unclear how many seek reimbursement for medical or mental health treatment associated with injuries incurred while competing on their teams. Between 2019 and 2021, 336 student-athletes graduated from the school, according to data provided by the athletic department.

"I competed for them and made them money over my time there, and to not be compensated — especially when I wasn’t on an athletic scholarship — is hurtful," said Sydney Freidin.

"I needed space to work on myself"

Freidin arrived at the UA fromĚýWestchester, California, in the summer of 2017, prior to the start of her freshman year. That first year wasn'tĚýeasy, with Freidin saying she didn't get along with the other three freshmen on the gymnastics team and often felt isolated.

"I was trying to figure out life without my parents, and gymnastics culture is very backwards from what real-life nutritionĚýshould be," she said. "I've been told false things about food my whole life."

Freidin said by the time she came to the UA, she'd already dealt with a coach who had unhealthy ideas about portion control. She said that, through gymnastics, she grew up in an environment where foodĚýwas viewed as unhealthy.

A self-proclaimed orthorexic — a person who is obsessed with his or her health — she said she only put healthy things into her body.

Freidin competed in two meets her freshman season, scoring a career high on the balance beam at a February 2018 meet at Oregon State. That April, everything changed. Freidin underwent a postseason body composition test meant to track athletes' progress. Her trainer told her that the team's nutritionist was concerned by her body composition, and within a few days she was sent to the team's doctor, who told her she was being diagnosed with anorexia.

"The doctor took me into an office and made me call my mom," Freidin said. "I was sobbing through the phone call."

The UA sent Freidin to a nutritionist who she says only made the condition worse. She studied abroad for a semester, but with the eating disorder diagnosis and guidelines from the nutritionist hanging over her head, "It was not an enjoyable experience, to say the least."

Competing was still fun, she said. SheĚýtook part in every meet during her sophomore season, setting another career high on the balance beam in January 2019 against Washington and a career high on the floorĚýexercise against Cal later that month. SheĚýtraveled to Corvallis with the team for NCAA Regionals, where she competed in both the balance beam and floor exercise.

Following the regionals, Freidin and her parents went out to dinner with the team at The Old Spaghetti Factory.

"There was nothing I could eat and I was freaking out. I got into a yelling fight with my mom in the restaurant," Freidin said.

Freidin's parents and coaches soon gave her a choice: Go to treatment for her eating disorder or be done with gymnastics.

She returned home to Los Angeles and began treatment at a local center, where she remained for the next three and a half months while living with her parents.

While there, she was visited by UA coach John Court, who she said was extremely supportive.

Freidin planned to return for her junior season, but said that her body and brain had changed. She began paying for her own psychiatrist, but by then, her congenital hip dysplasia had become a problem and the torn labrums in her hip had been diagnosed.

"The treatment team said I could no longer physically do gymnastics in October 2019," Freidin said. "I had gym pulled from me. I didn't get the choice."

She spent a few months as team manager, but said it was too hard to be around gymnastics and not compete. Freidin returned to California for residential treatment for her eating disorder in May 2020; herĚýparents' insurance covered the cost of her six months of residential, partial hospitalization and intensive outpatient treatment.

Freidin graduated in May, then learned she'd need operations on both hips to repair her torn labrums and two surgeries to correct her hip dysplasia.

The UA granted her medical coverage for post-eligibility surgery on both of labrums, which fall within the extended time period allotted, and agreed to cover 12 post-op physical therapy visits. Per NCAA guidelines, universities can cover one physical therapy session per week for two years after a student-athlete graduates, which covers Freidin through May 2024.

'Actions speak louder than words'

A few months after graduation, Freidin received the letter that her mental health-relatedĚýreimbursements would cease in November, with no further explanation. She appealed the decision, filling out the appropriate forms and sending emails to Heeke and other athletic department and school officials.

On Aug. 19, she heard back from Heeke, who referred her to a second letter from van der Merwe. In it, Freidin's name was spelled incorrectly.

"Mental health conditions... are not covered by the NCAA post-eligibility medical coverage policy as an athletic injury," the letter said. "We also reviewed your case individually and determined that your diagnosis of eating disorder is a mental health condition and was most likely a pre-existing condition, though not formally diagnosed. We were able to provide support for mental health services during your time as a student, but per our policy, that does end when you graduate."

NCAA spokesman Christopher Radford said mental health resources and services provided by member schools should be consistent with the NCAA's Mental Health Best Practices, a 38-page that includes screening tools toĚýevaluate issues — including disordered eating — in student-athletes.

It also contains guidance for student-athletes who are leaving the program. The NCAA recommends that "athletics administration, sports medicine personnel and licensed practitioners who are qualified to provide mental health services jointly review" the issue.

While the additional considerations aren't formal guidelines, the guide said, they're still "important considerations that should be thoughtfully addressed." The guide offers up several questions to assist in the process, including:

- Is there a clearly delineated transition of care plan for student-athletes who are leaving the college sport environment that is in the interest of continuing medical care and student-athlete welfare?

- Who is responsible for initiating transition of care?

- Who is responsible for providing student-athletes with information about community mental health resources?

It's unclear if such a plan is in place at the UA. With all avenues of appeal exhausted, Freidin said she's lucky to be on her parents' insurance as she continues with treatment.

Freidin said that even though months have passed since the UA stopped her coverage, she's still unhappy with the school's decision.

"Medical coverage for my eating disorder is a dime in (the UA's) bucket, whereas it is a massive amount of change in mine," Freidin said. "For a university that prides itself on (taking care of student-athletes' mental health), its actions speak louder than words. Not only did I put my physical body at risk for them, I also placed my mind in a tumultuous and vulnerable space."

Contact Star reporter Caitlin Schmidt at 573-4191 or cschmidt@tucson.com. On Twitter: @caitlincschmidt