Nancy Adams found the drawing at a cluttered secondhand store in Globe in 1991.

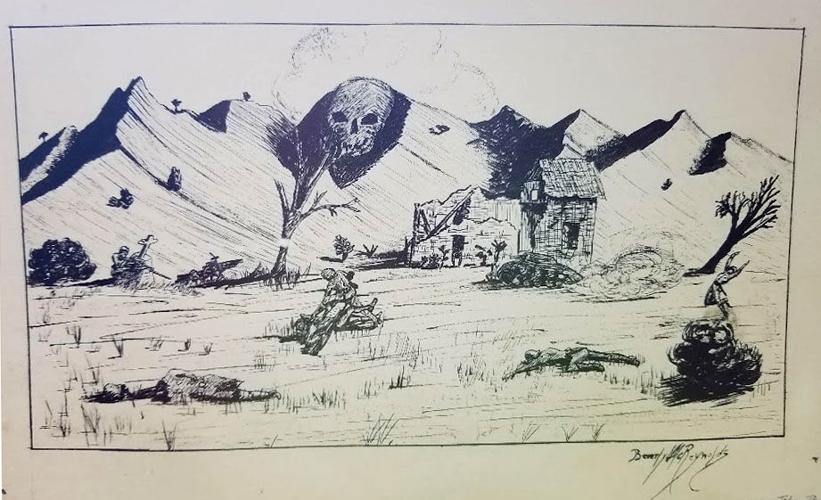

It depicted a gruesome battle scene, inked in black on a small rectangle of yellowed paper т soldiers killing each other or already dead in the shadow of a mountain with a skull for a face.

The work was signed by a man named Beverly McReynolds and included a date and a location: May 8, 1943, Talara, Peru.

It wasnтt the sort of thing Nancy was normally drawn to, but it stopped her in her tracks.

тIt was just so compelling to me. The technical skill was undeniable,т said the former public school psychologist turned college professor. тThe drawing itself was really very small, but the content was so huge.т

Nancy bought the loose sheet of 8-by-6-inch paper for a buck or two and took it home to Mesa, where she had it professionally framed. The drawing went with her a few years later, when she moved from УлшжжБВЅ to Marshalltown, Iowa.

People are also reading…

She was careful to make sure the frame didnтt cover one of her favorite details: the thumbtack holes in the corners of the drawing.

тSomeone put it up and was looking at it. And then they were done looking at it, but they didnтt destroy it,т she explained.

The drawing made by Beverly McReynolds. Found in a junk shop in 1991, Globe, Ariz.

Nancy kept the rescued piece of wartime art hanging in her home or on display in her office ever since. She even took it to class a few times, at the тmilitary friendlyт community college where she teaches psychology, to help illustrate lectures on art therapy, PTSD and тthe healing powers of expression,т she said.

After a while, though, Nancy began to wonder if it was right to keep something so painful and personal. Thatтs when she set out to find where the drawing had come from in hopes of returning it.

The artist

Bill McReynolds never really knew his father.

He was still a toddler when his parents divorced. He was not quite 5 when his dad killed himself in 1950 at the age of 31.

Bill remembers going to the funeral and seeing his father in his open casket, but he has almost no other memories of the man.

Bill said his family members rarely talked about Beverly. тMaybe it was because he committed suicide, I donтt know,т the lifelong УлшжжБВЅ resident said.

Billтs mother later told him that Beverly was nervous and plagued by chronic pain and nightmares when he came home from the war, with a hair-trigger temper that frightened her.

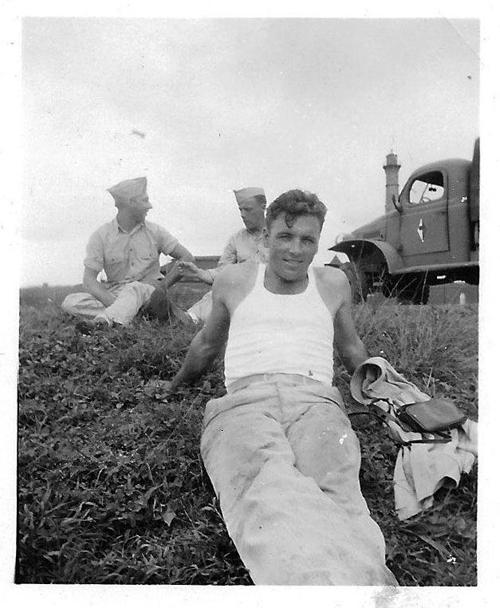

УлшжжБВЅ veteran Bill McReynolds.

Almost everything else Bill now knows about his father he learned from a box of letters, photos and documents he inherited from his Grandma Nora, Beverlyтs mother, after she died in 1993.

Beverly McReynolds was born in Kansas on Oct. 4, 1918, but grew up in УлшжжБВЅ, where Nora worked as a nurse caring for tuberculosis patients.

As a young man in the late 1930s, he took a ranching job in Willcox, where he met a local girl named Velva Fraker.

A short time later, he joined the Army and served with an artillery unit in Panama, Peru and eventually the Pacific Theater.

Between postings he returned to the U.S. at least twice: First in October 1943 to marry Velva at Fort Bliss in El Paso, Texas, and again in the late summer of 1944, when the grinning new father was photographed in uniform holding his infant son.

Beverly McReynolds and his infant son Bill.

At some point during his service, Beverly suffered a spinal injury that haunted him for the rest of his life.

Bill believes his dad saw action in the Philippines and possibly New Guinea, but he doesnтt know any specifics. The fighting never reached the coastal town of Talara, Peru, where the U.S. established an air base and a refueling station for the Pacific Fleet.

Bill tried to get his fatherтs service records from the military, but he was told they had been lost in a fire. тIt was kind of a dead end,т he said.

Beverly wanted to work as an artist after the war, but his injury left him with pain and numbness in his arms and hands that made it difficult to hold a pen or a paintbrush. He managed to finish art school, but it was a struggle, Bill said.

He eventually had surgery on his spine at a VA hospital, but his physical and mental health continued to deteriorate.

Bill is convinced his father suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder.

тNow thereтs a lot of recognition (of PTSD), but back then there wasnтt,т said Bill, who served in the Navy in the early 1960s. тPeople were pretty much on their own. You either made it or you didnтt.т

Velva stayed in contact with Beverlyтs family after he died, and she made sure Bill got to see them, too.

He said his mom also used to visit her first husbandтs grave at South Lawn Cemetery once a year or so, and he would escort her there later in her life.

Sheтs gone now, too, but he still carries on that tradition. Each year around Memorial Day, he heads to South Lawn to bring his father and his Grandma Nora a fresh bouquet of plastic flowers and tidy up their headstones.

The connection

Nancy began her search for the artist behind her prized, antique-store find in 2017. She eventually tracked Bill down in УлшжжБВЅ with the help of the internet and her friend, Mary.

That December, Nancy said, she sent Bill a тcarefully worded letterт but did not include a copy of the drawing, just in case she was contacting the wrong person or someone who might be bothered by such a violent scene.

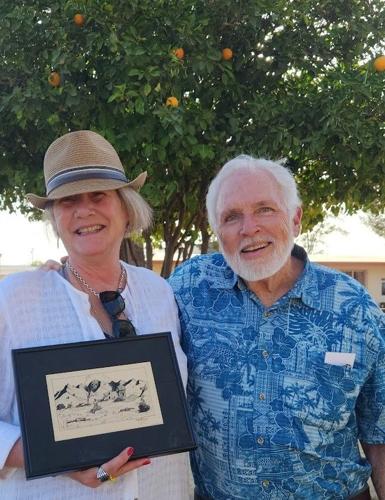

Nancy Adams and Bill McReynolds pose with a drawing McReynolds' father, Beverly McReynolds, made when he was stationed overseas during World War II.Т Т

Bill quickly wrote her back to confirm that she had found the right family.

He also emailed her a few photographs of his father, along with two of his pen-and-ink drawings from before the war, each depicting a woman and a cougar. The earlier pieces bore the same lines and the same technique, only without the тdark content,т Nancy said. тItтs just very clearly the same hand.т

Bill said it was obvious from the start that his fatherтs drawing meant a lot to Nancy and that she had found a way to put it to use in a way that helped people. He told her he wanted her to keep it.

Nancy still gets emotional talking about it.

тItтs enriched my life, knowing the backstory and knowing Bill,т she said. тI have just been humbled and honored by his transparency and openness with me.т

The two have kept in touch in the six years since that initial flurry of emails, and Nancy has written an essay detailing what she has learned about the drawing and the people connected to it.

She said she felt like she has been trusted with somebodyтs legacy, and she has a responsibility to tell that story тfor Bill and Beverly and for those who serve and come back and donтt have the support they deserve.т

тI canтt be the only person who knows what happened here,т she said.

Bill and Nancy finally arranged to meet in person earlier this year, while she and her husband, Jeff, were on a trip to УлшжжБВЅ in May.

Bill took them to see his fatherтs grave at South Lawn. Nancy brought along the drawing in its frame, so Bill could hold it in his hands for the first time.

The whole experience has been a little strange for Bill, who said he still feels like тjust a bystanderт in the story of his dadтs short life.

But heтs grateful to Nancy for all she has done. Getting to see his fatherтs dark drawing from the war has helped him to better understand a man heтs only ever known from photographs and a few of his sketches.

тHeтs almost more a part of my life now than he was back then, because Iтve learned so much about him,т Bill said. тI have these pictures, and theyтre more significant now in a way.т

Watch now: After a two-year hiatus, УлшжжБВЅ's Veterans Day Parade made its downtown return Friday, Nov. 11.

The parade route started at North Granada Avenue and West Alameda Street, then ran south to West Cushing Street before looping back around.

Video by Jesse Tellez / УлшжжБВЅ.