In 1972, Quentin Bryson, a УлшжжБВЅ developer, named a road that connected Craycroft Road, just south of Sunrise Drive, to his new subdivision called Sunrise Territory Village, whose streets were named for the military forts in the УлшжжБВЅ Territory.

This road was named Territory Drive in honor of the Territory of УлшжжБВЅ, which existed from 1863 to 1911, before УлшжжБВЅ became a state.

In 1872, 100 years before, an unknown pioneer wrote an account of a journey he made around the УлшжжБВЅ Territory a few months earlier in the УлшжжБВЅ Miner newspaper in Prescott and shared with readers what they would have seen if they were on this trip with him.

On Oct. 28, 1871, the anonymous pioneer writer and Maj. Charles H. Veil began a journey from Prescott, (named for William H. Prescott, a 19th-century historian), their mountain home of about 1,200 residents which was the county seat of Yavapai County (named for the Yavapai tribe).

People are also reading…

A view of northern УлшжжБВЅ at the base of San Francisco Mountain.

They departed in a buggy on a clear cold night with a pale moon. The pair headed in a northwesterly direction, traveling in the darkness of night likely to avoid the Apache threat, firmly grasping their loaded rifles as they passed the graves of slain pioneers.

They drove to Mint Valley and then into Skull Valley (according to this pioneer writer, the name derived from the fact that when the first European Americans arrived in the valley, they found huge piles of bleached skulls that had once belonged to Maricopa and Apache warriors who had fought a bitter battle against one another there. Although, other derivations do exist.)

A group of Apaches in front of their wikiups near Camp Apache, УлшжжБВЅ in 1873.

Their journey continued south into Kirkland Valley (named for William H. Kirkland, an УлшжжБВЅ pioneer who discovered gold in the valley in 1863).

Then taking a westerly direction, they entered Bellтs Canyon (named in honor of Richard Bell, killed in this canyon), a long, rocky and dangerous pass that saw much loss of life due to Apache ambushes. The pair made it through unscathed and went on their way to Camp Date Creek, near Date Creek (a name likely derived from the date-like fruit of the yucca plant that grew abundantly along the creek) on the old stage road from Prescott to La Paz.

This military site was comprised of clean and comfortable adobe buildings and had a sutler store. The Army campтs main objective was to provide protection to travelers on the stage coach road. The nearby creek had some water and cottonwood trees as well as willow trees of good sizes grew on its banks.

They spent the night in the safety of the garrison. After breakfast the next morning, they watched soldiers issue rations of corn and beef to a large group of unknown Indigenous people.

Around 10 a.m., Major Veil completed his work at the site and they continued on their dusty journey on the stage road to Wickenburg (named for Henry Wickenburg, founder of the nearby Vulture gold mine).

A little later they entered the town of Wickenburg with its population of 500, of whom 200 worked at the nearby Vulture Mine. They drove their buggy on a Sunday afternoon into the streets of the town filled with people, some of whom were old acquaintances of the scribe, who had visited in 1864, when there was a total of about seven men, a tent or two and some rudimentary mining equipment in the area.

While Henry Wickenburgтs pioneer arrastra (a primitive crusher that was used in mining to grind ore) was still there, the founderтs tent had been replaced by an adobe home, and several fine businesses including A.H. Peeplesт Brewery and Saloon, and M. Peraltaтs hardware, mining and agricultural store had come into existence.

At the end of their time there, they departed Wickenburg in a buckboard wagon and rattled along down the Hassayampa River until they came to the Agua Fria Station (present-day Avondale) near the Agua Fria River at about 3 oтclock in the morning. The stage stop, according to this penman, was kept by Darrell Duppa, a well-known settler, credited with naming Phoenix.

Their short stay at the stage stop came to an end and the wooden wheels of the wagon began to roll again. Soon these wheels were leaving ruts in the nearby Salt River Valley before coming to a stop at Phoenix, the newly crowned county seat of the newly formed Maricopa County (named for the Maricopa tribe).

The writer would describe Phoenix in this manner: тSeated on high ground, nearly in the center of a valley тІ this young ambitious town has before it a future such as few towns in УлшжжБВЅ can expect. тІ It is a town of considerable importance, containing stores, boarding-houses, a jail, school house, many comfortable private dwellings, blacksmith and carpenter shops and various other buildings.т

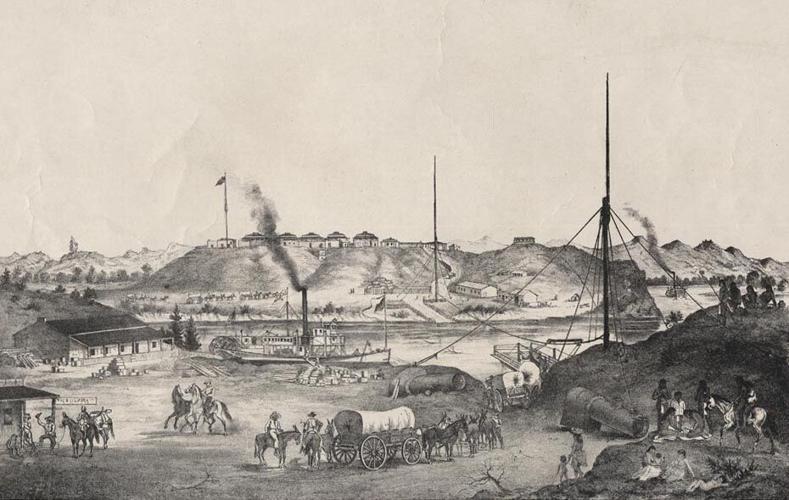

УлшжжБВЅ City (aka Yuma) and Fort Yuma on the other side of the Colorado River in the 1870s.

Their next stop was three miles up the valley at Mill City (now East Phoenix), where W. B. Hellings & Co. had its headquarters and mill. Along with the Hellings brothers, the pair тexamined the premises, consisting of a large, well-furnished adobe store, comfortable residences for owners and employees, and last but not least the flouring mill, which is a large three-story building, well roofed with lumber and shingles.т

The foursome climbed on top of the roof of the flour plant to get a view of the Salt River т the lifeblood of the communities in the area with their combined 1,500 or so souls т to the south, at this point being a width of between 250 and 300 feet and about 2ТН feet deep. There were also ancient ruins and canals everywhere the writer looked, reminding all of the civilization т the Hohokam т that once existed on this prehistoric river.

The duo was then picked up at the Hellingsт home in Mill City, chauffeured back to Phoenix and then in a southerly direction toward Maricopa Wells, south of the Gila River.

They are believed to have passed through the Pima villages of oval-shaped huts constructed of mud, poles and straw. The residents were divided into bands under minor chiefs, all of whom where under the head chief, Antonio Azul. This tribe, which is believed to have had villages on both sides of the Gila River, but mostly on the south side, was in continual war with the Apache tribe.

The writer shared: тBut a short time previous to our visit, a party of Pimas had killed some Apaches and as is their custom, the braves who did the killing were housed up, doing penance, we presume. While thus engaged they converse with nobody and water and provisions, etc. is carried to them. This, we were told lasts about thirty days.т

When the pair reached the Gila River, it was almost dry т at least where they crossed т and had been all the previous summer, likely due to the drought.

At their destination, Maricopa Wells, and the surrounding area there were, according to the pioneer, a total of about 400 Maricopa tribal members, a much smaller number than the nearby Pima tribe.

The Wells, as it was called informally, had been a stage stop on the old Butterfield Overland Mail route, and was still a way station for emigrants traveling to California. It had a large store, offering goods of every kind, wagon and blacksmith shops, and a good well of water which was plentiful even in the drought, located in a grassy valley. Itтs believed the Casa Blanca ruins located east of Maricopa Wells, were still there at this time.

Another writer described these ruins a couple of years earlier in this way: тOne of the most prominent (ruins) is that of the Casa Blanca. This stands several stories in height and looms far above every object on the plains around. The walls are six feet thick, plastered with a lime or cement which appears to defy the power of the elements. Over the door and windows the cedar timbers are in perfect preservation, although it must have been ages since these were hauled over the long route from their native forests. Such is the dryness of the atmosphere that time has produced but a slow change up on it.

тThe streets of the city of which this structure formed a prominent part can be traced by broken pieces of crockery ware and the elevation on each side. Immediately back is seen the canal which conveyed water to this city of the past, and to the extended field bordering on the city below.т

The next point visited was Gila Bend in the Gila River Valley. Following the Gila River, they arrived at Kenyon Station where they had a good breakfast before they started for Burkeтs Station, where they recovered from being sick.

The stage stop owner at Burkeтs Station took the refreshed travelers across the river to Agua Caliente Ranch, where they spent five days seeing all there was to see, including famous hot springs that had helped many sufferers to find relief.

They headed on to hit Stanwix Station, Mohawk Station and Filibuster Camp.

They also passed through Gila City, an almost deserted site that once saw the first gold rush in the УлшжжБВЅ Territory, on their way to УлшжжБВЅ City (now Yuma) at the end of the Gila River at the junction of the Colorado River.

There they were greeted by John S. Carr (later a mayor of УлшжжБВЅ) and likely learned on this trip that УлшжжБВЅ City had become the county seat of Yuma County (named for the Yuma tribe) a few months earlier.

Ad for W. B. Hellings & Co. in Maricopa County in the Weekly УлшжжБВЅ Miner on Sept. 30, 1871.

The town had a population of about 1,200. It had several large mercantile houses, one wagon and several blacksmith shops and one church (Catholic). It even had a newspaper, the УлшжжБВЅ Free Press (soon after called the УлшжжБВЅ Sentinel).

The last leg of their trip was up the Colorado River before heading back to Prescott. Along the entire length of the Colorado River along Yuma County (now Yuma and La Paz counties, gold, silver, and copper lodes were found. At the time, most of this ore was transported to Ehrenberg (named for mining engineer Herman Ehrenberg) т a town of about 500 including the Goldwater family т and then was shipped to San Francisco, California to process since no real machinery existed near the mines.

The writer arrived home at Prescott by early December 1871 and recovered from his trip before sitting down and writing up his adventure for the newspaper.

This is the third of our history quizzes. How much do you know?

David Leighton, the Star's Street Smarts columnist, is a historian and author of “The History of the Hughes Missile Plant in УлшжжБВЅ, 1947-1960.” He received a 2024 Historic Preservation Award from the УлшжжБВЅ-Pima County Historical Commission for his Street Smarts column in the Star. He named four local streets in honor of pioneers Federico and Lupe Ronstadt and barrel racer Sherry Cervi, as well as the Jonathan Rothschild Alamo Wash Greenway and the Nick C. Hall Ramada at Old УлшжжБВЅ Studios. Contact him at azjournalist21@gmail.com.