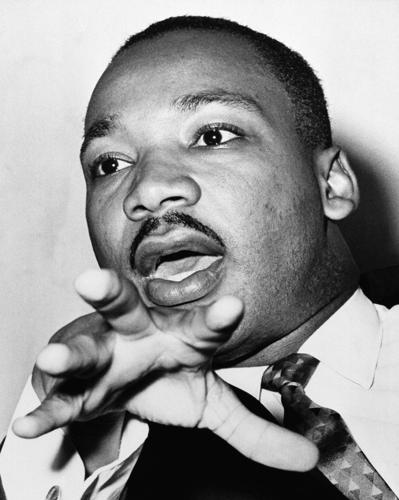

On the eve of the 49th anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.тs assassination in Memphis on April 4, 1968, longtime УлшжжБВЅans are sharing rich but little-known memories of his visits to the Old Pueblo.

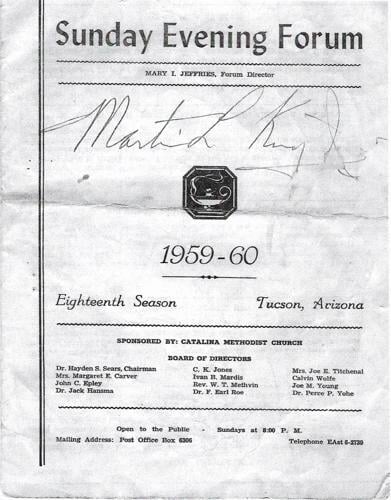

Kingтs connection to УлшжжБВЅ likely began in July 1956 while he was in the midst of leading the Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott. Mary Jeffries (later Mary Jeffries Bruce), director of УлшжжБВЅтs then-prominent Sunday Evening Forum, is believed to have sent a telegram to King asking him to come and speak.

Jeffries had begun the Sunday Evening Forum as a Sunday discussion group for young adults in 1940, at the old University Methodist Church, now Catalina United Methodist Church. Two years later, the group had become so large that it moved to the church's auditorium and was opened to the public. Soon it began to draw individuals of national prominence, including some who wintered in УлшжжБВЅ. In 1947, the Sunday Evening Forum moved to the УлшжжБВЅ High School auditorium, and then around 1950, to the University of УлшжжБВЅ auditorium, now called Centennial Hall.

People are also reading…

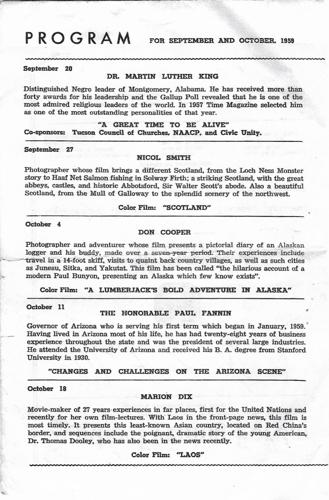

The correspondence between Jeffries and King continued through 1957 and 1958 with Jeffries sending letters, individual programs and the 1957-58 Preview of Programs for the forum т which included a visit by Sen. John F. Kennedy т hoping to interest the civil rights leader into taking a trip to УлшжжБВЅ.

By May 1958, it is believed that King had agreed to speak in УлшжжБВЅ on March 15 the following year. His plans soon changed, though, when on Sept. 20, 1958, while at a book signing in the Harlem neighborhood of New York City for his recently published тStride Toward Freedom,т he was stabbed by a black woman named Izola Curry, very close to the heart, with a seven-inch steel letter opener. While he survived the attempted murder and the assailant was put in a mental institution, the attack would change many of his plans as he recovered and recommitted himself to his nonviolent approach to bringing social change.

On Feb. 25, 1959, Jeffries announced in the newspaper that King had canceled his March 15 speaking engagement but rescheduled for later in the year.

On Sept. 20, 1959, after he delivered a sermon at the Second Baptist Church in Los Angeles, King flew to УлшжжБВЅ and was picked up by a member of the host committee to speak at the Sunday Evening Forum. His talk was co-sponsored by the УлшжжБВЅ Council of Churches, the УлшжжБВЅ NAACP and the УлшжжБВЅ Council for Civic Unity and was considered quite controversial at the time because of his views on race.

Robert L. Nugent, university vice president, introduced Dr. King to the capacity crowd in the auditorium, which was filled with mostly activists and members of the university community. The speech was titled тA Great Time To Be Aliveт т a fitting theme on the one-year anniversary, to the day, of the attempted assassination in Harlem.

King spoke to the ideals of using nonviolent methods in creating social change. He put into words his belief that one must not use force in this struggle тbut match the violence of his opponents with his suffering.т

He warned that the U.S. faced a difficult challenge to achieve racial integration but predicted that within five years much of the mass resistance of the time would be gone and that within 15 years most legal restrictions would be taken away in the states. He emphasized to the crowd that the final period would arrive with integration, тour ultimate aim.т

тSegregation is a festering sore, a cancer,т he told the UA crowd. тIt stifles the soul of the nation. We are not looking for an advantage, which would keep the same old problem т black supremacy would be as bad as white supremacy т but we seek equality of all races. We are not seeking racial equality just to combat Communism, but because such equality is right.т

Jacque (Barnes) Price, then a child, recalls her mother, Mrs. Freddie Barnes, taking her and her brother to see King at the auditorium.

тI remember attending, listening and being impressed with this black man, preacher and leader,т she shared in a recent email interview with the Star. тWhen King finished speaking, she led us to the front to meet this man and to request his autograph. She saw what potential and promise in him that we, as children, may not have realized.т

Rev. Casper Glenn, now 95 years old, was pastor of УлшжжБВЅтs Southside Presbyterian Church at the time of Kingтs visit. He attended the speech and was introduced to King by Jeffries at a reception afterward, in which Jeffries mentioned that Glenn was the pastor of a multiracial church. King became keenly interested in this church and made arrangements to visit it.

The following day, in the morning, Glenn picked up King, in his 1958 Plymouth station wagon, in front of the Pioneer Hotel on Stone Avenue. Brother Glenn, as King referred to him during their time together, drove King to Southside Presbyterian, on West 23rd Street, where he showed him photos he had taken of the racially mixed congregation, whose majority at the time was Native American, especially Papago (Tohono Oтodham) Indians.

Glenn remembers that upon seeing the photos, King said he had never been on an Indian reservation, nor had he ever had a chance to get to know any Indians. On the spur of the moment, he asked to be taken to the nearby reservation, Glenn related in an exclusive interview last week with the Star.

The two traveled on Ajo Way to Sells, on what was then called the Papago Indian Reservation. During the drive, Glenn recalls King telling him of his future plans of going into Birmingham, Alabama, to protest segregation there. Glenn expressed his distaste for the idea, calling Eugene тBullт Connor, the public safety commissioner of Birmingham who was in charge of the police and fire department, a тraging beast.т

King scolded Glenn, saying тYou shouldnтt call him thatт and asked Glenn to pull over so he could pray for God to change Connorтs heart in regards to segregation. Several times during the trip the deeply religious King repeated the phrase, тI just want to do Godтs will.т

When the two ministers arrived at the tribal council office, the tribal leaders, including chairman Enos Francisco Sr., police chief George Norris, Henry Throssell and other people there, were surprised to see a man they knew of and felt very honored to meet. Francisco brought sodas and chuchuma (bread similar to tortillas) out for their guests to enjoy. King seemed as anxious to talk to them as they were to him. King was very careful with his questions, Glenn recalled, and seemed to not want to be embarrassed by his lack of understanding of their tribal heritage.

тHe was fascinated by everything that they shared with him,т Glenn said.

The pair then visited the Presbyterian church in Sells, which had recently been built from funds provided by the national Presbyterian church, though much of the construction was done by church members.

тThe pastor was white; Pastor Paul Townsend was his name. He was thrilled to meet King, and King asked him a few questions about his ministry,т Glenn said.

While on the way back from the reservation, King expressed his appreciation of getting to meet the Indians. When they arrived in УлшжжБВЅ they went directly to the airport, since King said he had to dictate some letters to his secretary in Alabama. According to Glenn, King left УлшжжБВЅ around 4 p.m.

When King made his second visit to the Old Pueblo, in 1962, Cressworth Lander, a local activist, met him at the airport. Lander recalled in an interview with the Star in 2003: тThere was a major civil rights movement going on in УлшжжБВЅ. A lot of things were happening with the desegregation of all eating establishments.т

On March 11, 1962, King preached тPaulтs Letter to the American Christiansт at 11 a.m. at the Catalina (United) Methodist Church.Т

David Yetman, later a Pima County supervisor and the host of the PBS shows "The Desert Speaks" and "In the Americas with David Yetman", was a member of the choir at the church, along with his friend Bill Broyles, at the time. After the choir sang that morning, the two of them quickly went down to the front pew of the filled church auditorium to listen to King's sermon.

Yetman was a junior at the University of УлшжжБВЅ and familiar with King's work, having read his book "Stride Toward Freedom." He remembers King expressed his thoughts about racial injustice in the country in such a manner that it was uncomfortable for many people, because what he spoke about was so clear to many.

Following King's sermon, he attended the normal luncheon at the Fellowship Hall at the church. The minister, Dr. Hayden Sears, then asked Yetman to drive King back to the Santa Rita Hotel, where he was staying. Yetman recalls that during the drive he attempted to sound very intelligent but believes he sounded more like a babbling idiot. He remembers one question worth King's time т "What would you recommend for someone of my age and skin color to do in regards to civil rights?" т but doesn't remember King's exact answer, although he notes it was likely a logical response.

Yetman, to this day, holds Dr. Sears in high regard for having King speak at his house of worship, at a time when King was being falsely accused of being a communist by those who disliked or wanted to discredit him. Sears faced discontent among some of his own parishioners and as well as those of other churches in town. Some local media also opposed Sears allowing King to speak there.

Next in his schedule that day, King visited the УлшжжБВЅ Press Club Forum.

That night, at 8 p.m., King was again on the stage of the UA auditorium, ready to share his topic тStride Toward Freedom.т He was presented to the packed house by Francis A. Roy, UA liberal arts dean. Kingтs oration covered both the success and lack of success by the civil rights movement up until that time.

King stated that the policy of non-violent direct action, such as the lunch counter sit-ins and freedom rides, had opened 150 eating establishments to blacks in the Deep South.

But he talked about apathy among members of his race when it came to voting.

тWe must place emphasis on voter registration,т he said.

There were about 5 million blacks in the South at the time, and only about 1.3 million were registered voters.

King also said he was submitting a second emancipation proclamation, aimed at abolishing discrimination in housing, education and employment, to President Kennedy. He declared that its issuance тwould be a great step forwardт on the eve of the 100th anniversary of the first Emancipation Proclamation in 1863.

Following the forum, King was honored with a reception at the Student Union Building hosted by the local chapter of the NAACP. He left the next day and is not known to have returned to УлшжжБВЅ.

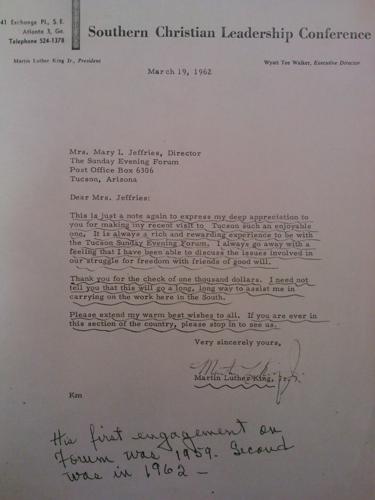

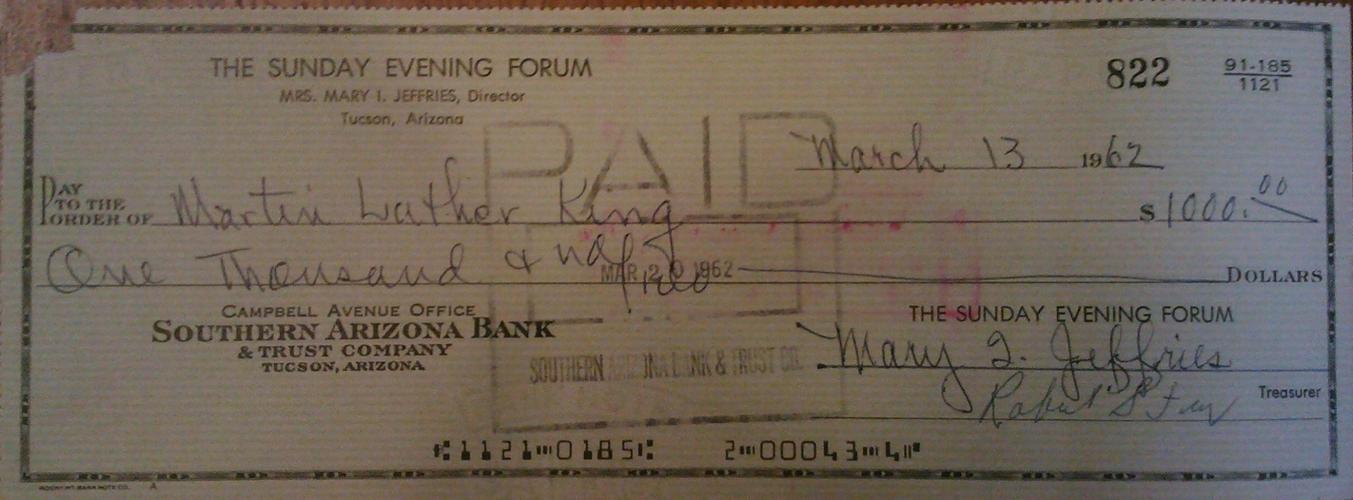

Two days later, Jeffries sent King a check for $1,000 for his speaking engagement. King sent a thank-you letter saying the money would help in his work in the South.

On Jan. 18, 2016, УлшжжБВЅ celebrated Kingтs birthday by renaming a street at the UA Tech Park at The Bridges, south of 36th Street near Kino Parkway, as M L King Jr. Way.

Special thanks to Jerry Flanary and the staff at the UA Special Collections Library, Pam Lawrence, Catalina United Methodist Church, and Rev. Alison J. Harrington & Teena Cross, Southside Presbyterian Church for research assistance on this article. Other sources included a phone interview with Rev. Casper Glenn, pastor of the Southside Presbyterian Church in the late 1950s and early 1960s, on March 28, 2017; and emails from Jacque (Barnes) Price, who attended the King talk in 1959.

David Leighton is a historian and author of the book "The History of the Hughes Missile Plant in УлшжжБВЅ, 1947-1960." If you have a street to suggest or a story to share contact him at Streetsmarts@tucson.com