A barbecue on West Speedway. Picnics and sing-alongs on the fairways of El Rio Golf Course. Marches, confrontations with police, arrests, negotiations and ultimately, compromise.

Those events were among the defining moments and symbols of a 55-year-old fight over the west sideŌĆÖs El Rio Golf Course that led to a major win for ├█Ķųų▒▓źŌĆÖs burgeoning Chicano rights movement ŌĆö with no little help from then-University of ├█Ķųų▒▓ź student and activist Ra├║l Grijalva.

Grijalva, who died Thursday at 77 years old after a year-long battle with lung cancer, was among many activists and west side neighbors who successfully pushed ├█Ķųų▒▓ź City Hall to set aside a healthy section of the golf courseŌĆÖs western edge as a park ŌĆö now known as Joaquin Murrieta Park. Living on ├█Ķųų▒▓źŌĆÖs south side but already active and steeped in west side issues, he both helped organize and marched in the effort to create the park.

People are also reading…

He and his colleagues also persuaded city leaders to build the El Rio Neighborhood Center on a parking lot on the golf course. It was the first of many neighborhood centers to spring up in ├█Ķųų▒▓ź over the next few decades. The successes followed both a brief takeover of the golf course by activists and other neighbors, rallies and playful ceremonies both inside and outside the course and later, arrests of some participants.

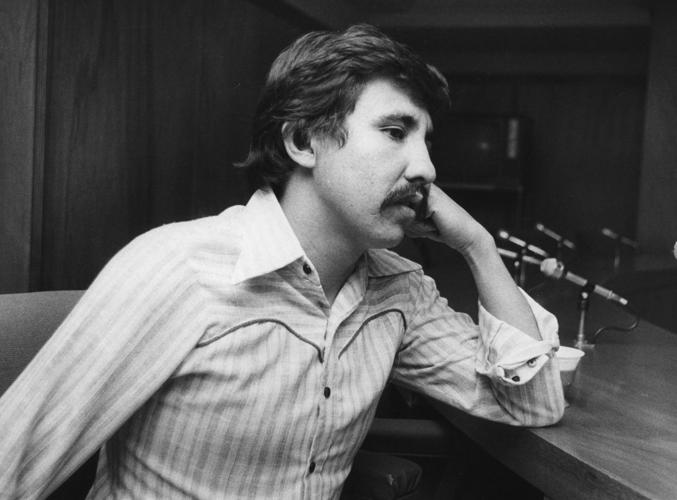

A push to carve out a section of El Rio Golf Course for the creation of a park and later a neighborhood center on ├█Ķųų▒▓źŌĆÖs west side helped propel the political career of Ra├║l Grijalva, seen here in 1977 as a member of the TUSD governing board.

It was not the first or last political cause Grijalva would embrace as a University of ├█Ķųų▒▓ź student in his early 20s, before he made his first venture into electoral politics when he ran unsuccessfully for the ├█Ķųų▒▓ź Unified School District governing board in 1972 and then successfully in 1974.

He had already worked in support of C├®sar Ch├ĪvezŌĆÖs United Farmworkers and demonstrated against the Vietnam War. Later, he would burn his draft card on the UA campus, recalled Lupe Castillo, a retired Pima Community College history professor and longtime friend who worked closely with Grijalva during his activist days.

Grijalva fought for bilingual education and other programs to better the schooling of Latinos who had been forbidden to speak Spanish at school during GrijalvaŌĆÖs elementary school years. He also got involved in a successful fight to save nearby Davis Elementary School west of downtown from closing, as the ├█Ķųų▒▓ź Unified School District governing board was proposing. He also was an early activist in the fight for what he saw as the rights of undocumented immigrants.

To Sal Baldenegro, a Chicano activist in the 1960s and 70s who with Grijalva were among the leading organizers of the El Rio drive, the effort ŌĆ£was a historic phenomenon, a defining moment in ├█Ķųų▒▓ź history,ŌĆØ Baldenegro wrote in a column for the ├█Ķųų▒▓ź Citizen shortly before the newspaper closed in March 2009.

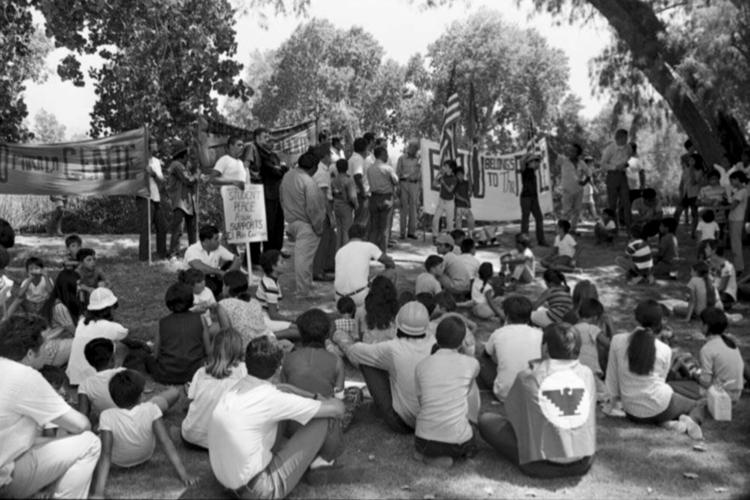

Protestors march to El Rio Golf Course from Tully Elementary School on August 22, 1970. The community effort to get a park and neighborhood center carved from land dedicated to the golf course led to a major win for ├█Ķųų▒▓źŌĆÖs burgeoning Chicano rights movement.

ŌĆ£It proved a united community can indeed move City Hall. And it fundamentally changed the political landscape and dynamics of ├█Ķųų▒▓ź,ŌĆØ Baldenegro wrote.

In 2012, Arnold Palacios, then executive director of ├█Ķųų▒▓ź Youth Development, a social service agency, told Star columnist Ernesto Portillo that the El Rio conflict ŌĆ£was the focal point of social justice for all us in ├█Ķųų▒▓ź.ŌĆØ He also marched on the golf course back in 1970.

But ŌĆ£in a way we didnŌĆÖt see it as victories,ŌĆØ Castillo said of their successes at El Rio. ŌĆ£We saw it as a process we were going toward. We had the total sense of keeping our eyes on the prize that this is what weŌĆÖve done now to go forward,ŌĆØ

The next steps were BaldenegroŌĆÖs unsuccessful run for the City CouncilŌĆÖs West Side Ward 1 seat in 1971, and GrijalvaŌĆÖs efforts to win a seat on the TUSD board, she said.

ŌĆ£The idea was to open the possibility of leadership among Mexican-Americans,ŌĆØ Castillo said. ŌĆ£We didnŌĆÖt see these things as victories and we didnŌĆÖt see them as defeats. We saw it as part of the process of going forward.ŌĆØ

ŌĆśEl Rio was the tip of the icebergŌĆÖ

Baldenegro later ran a social service agency for youths and worked for the UA as assistant dean for Hispanic student affairs before retiring. He has written about and given an oral history about the El Rio events in the past. But he didnŌĆÖt respond to requests from the Star through a family member and a friend for an interview about them.

But in an interview the day after GrijalvaŌĆÖs death, Castillo made it clear that the fight over El Rio was part of a much broader struggle for Latinos at the time.

ŌĆ£El Rio was the tip of the iceberg, and underlying that were the greater issues,ŌĆØ Castillo said. ŌĆ£It wasnŌĆÖt just simply wanting a park for the sake of a park. It represented the symbol of retaking territory, that underlay all other issues we were confronting at that time ŌĆö poor education, poor health services and poor infrastructure.

In 2012, Arnold Palacios, then executive director of ├█Ķųų▒▓ź Youth Development, a social service agency, told Star columnist Ernesto Portillo that the El Rio conflict ŌĆ£was the focal point of social justice for all us in ├█Ķųų▒▓ź.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£There was no question that discrimination and segregation and racism were very embedded in ├█Ķųų▒▓ź. We could see it and we saw it very clearly with what became destruction of barriosŌĆ£ in downtown ├█Ķųų▒▓ź to build the ├█Ķųų▒▓ź Convention Center, she said.

As Castillo and Baldenegro recall, Barrio Hollywood, the Latino-dominated neighborhood just across Speedway from the golf course, had in the late 60s no paved streets or sidewalks and many of its residents had relied outhouses due to a lack of sewer service in the neighborhood.

ŌĆ£And there was nowhere for kids to play ŌĆö nothing at all,ŌĆØ Baldenegro said when giving an oral history interview in 2011 for the state-run ├█Ķųų▒▓ź Memory Project. ŌĆ£I grew up there. We played in empty lots or on the streets, period. Now, we could have gone to Oury Park (on 600 W. St. MaryŌĆÖs Road, but Oury Park was, for the most part, a swimming pool. It really wasnŌĆÖt a major park.

ŌĆ£But in order to get there, we had to cross a [busy] street. Or we could have gone to Menlo Park on the south. But in order to get to there, weŌĆÖd have to cross St. MaryŌĆÖs, which was a major thoroughfare.ŌĆØ

The nearest parks to the golf course ŌĆö Menlo, Oury and Estevan ŌĆö averaged three to seven acres, compared to 122 acres for El Rio, wrote Jordan Javier, a UA graduate, in a peer-reviewed history of the El Rio controversy published in 2018 in Footnotes, a journal published by UAŌĆÖs History Department.

The course itself was seen by the activists as a symbol of ├█Ķųų▒▓źŌĆÖs racist past. It was ├█Ķųų▒▓źŌĆÖs first grass golf course, built in the late 1920s, and was a private course and country club until the city bought it in 1968.

It hosted the ├█Ķųų▒▓ź Open from 1945 to 1962. Ben Hogan, Babe Didrikson Zaharias, Arnold Palmer, Byron Nelson and Sam Snead were among the leading lights of pro golf who played at the open during those years, according to a history of the course on .

But as Barrio Hollywood residents recalled it, the only time they could go on the course prior to their demonstrations and takeover was to be caddies.

Palacio told Portillo that when he first set foot on the course as a university student in 1970, he found a huge contradiction.

All around him were lush fairways and putting greens, filled verdant beauty from the golf courseŌĆÖs manicured grass and abundant, watered trees. The golf course was an island in stark contrast to the well-worn working class barrios surrounding it, he told Portillo.

Much of the organizing work that led to the El Rio takeover by residents happened at the Chicano House, a place where leaders of the burgeoning community movement met regularly to hatch plans and strategies for dealing with issues of neighborhood concern.

The dichotomy reflected the disparity between the barrios and most of ├█Ķųų▒▓ź. The golf course ŌĆ£crystallized the condition of the community,ŌĆØ said Palacios, a long time educator.

ŌĆ£It was distressing for parents walking their children from any of these parks while El Rio lay so close yet unattainable. It would continue to appear to be unattainable considering the stalemated pace of negotiations between the El Rio coalition and ├█Ķųų▒▓ź City Council,ŌĆØ Javier wrote in his paper.

ŌĆ£Among the few Chicanos able to visit El Rio (caddies and restaurant workers) the lush beauty of El Rio expressed the discrepancy between their undeveloped neighborhoods and this park with green grass, ponds, and trees,ŌĆØ Javier wrote.

In the late 1960s, candidates for the Mayor and City Council came to the west side to campaign and were told by residents they wanted their commitment for a park and neighborhood center, if they were elected. They promised to do that, but never followed through, Baldenegro said in his oral history.

Neighborhood leaders decided they had to ratchet up their efforts a step further.

ŌĆśEl Rio belongs to the peopleŌĆÖ

Much of the organizing work that led to the El Rio takeover by residents happened at the Chicano House, a place where leaders of the burgeoning Mexican-American rights movement met regularly to hatch plans and strategies for dealing with issues of neighborhood concern. The ŌĆ£houseŌĆÖŌĆÖ actually had three different locations during its existence, including one owned by BaldenegroŌĆÖs mother, Castillo said.

She and Grijalva were both active in the Chicano house and thatŌĆÖs where they first met, Castillo said. While Grijalva never lived in Barrio Hollywood, he and his wife Ramona were very involved in neighborhood issues.

When the neighborhoods served by the Chicano House and women there who had children were trying to set up a little school there, ŌĆ£Ramona was very involved in that,ŌĆØ Castillo said. As for the El Rio controversy, ŌĆ£I canŌĆÖt remember not being at a meeting where he wasnŌĆÖt there participating,ŌĆØ Castillo said.

Also active there was the El Rio Coalition, representing barrios closest to the golf course, including Barrios Hollywood and Anita.

The golf course takeover began during a rally and march that was called after negotiations with the city proved fruitless, Baldenegro said. About 600 residents had marched through Barrio Hollywood neighborhoods to get to the golf course, and started a rally with seven speakers. Baldenegro was about to start making the seventh speech when a woman in the crowd cried out, ŌĆ£Enough talking. LetŌĆÖs go to our park.ŌĆØ

For the next few hours, kids were running and adults were marching up the park, stunning golfers, one of whom threw a golf club at kids, Baldenegro recalled in his oral history. Then the adults decided to toss a picnic.

ŌĆ£We went home, got the grills, and went and bought meat and tortillas and whatever, and we grilled, and we just had a picnic ŌĆö took over the golf course ŌĆö because the golfers left. The golfers got mad, got upset. Some diehards stayed and tried to play golf, but they couldnŌĆÖt,ŌĆØ Baldenegro recalled.

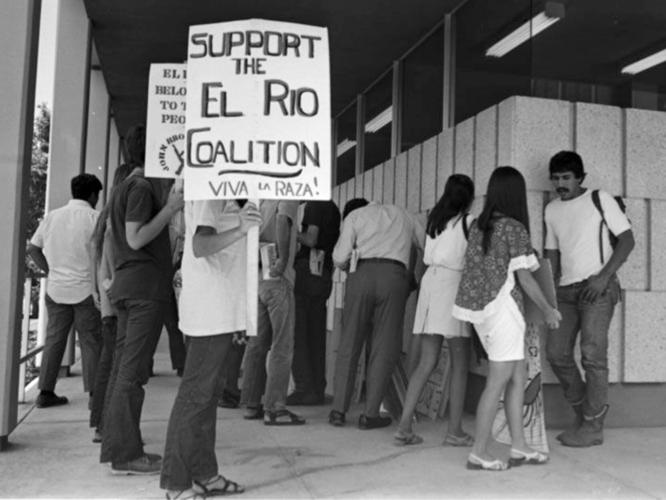

And then from that point on, for the next three or four months, the neighbors tried to take over the course once a week, but city police were now on the scene, complete with riot gear, and from then on, kept them from entering, he recalled.

At times during those attempted takeovers, there were arrests and some violent incidents. But eventually, the city and the neighbors settled on building the neighborhood center and creating the park.

Protestors picket ├█Ķųų▒▓ź City Hall on August 19, 1970. The fight over El Rio was part of a much broader struggle for Latinos at the time, says Lupe Castillo, a retired Pima Community College history professor and longtime friend of Ra├║l Grijalva.

The neighborhood center, once built, was designed to provide services demanded by the community, recalled Castillo: ŌĆ£a day care center, a senior center, a public library, an auditorium for neighborhood meetings and spaces providing services such as health care and room for students to study, she said.

ŌĆ£It became a model that served for establishing neighborhood centers across the city,ŌĆØ she said.

The center also was quickly decorated by some of ├█Ķųų▒▓źŌĆÖs early murals, first painted by Antonio Pasos and later by David Tineo. Both became renowned muralists over the next few decades.

The most important one at the center, by Pasos, showed neighborhood members of the El Rio Coalition marching forward, ŌĆ£saying El Rio belongs to the people,ŌĆØ Castillo said.

ŌĆ£It was murals that expressed the desires of justice and the identify of people and their pride and their history and who they were,ŌĆØ she said. ŌĆ£ThatŌĆÖs where it started. Right there in El Rio, at the neighborhood center.ŌĆØ