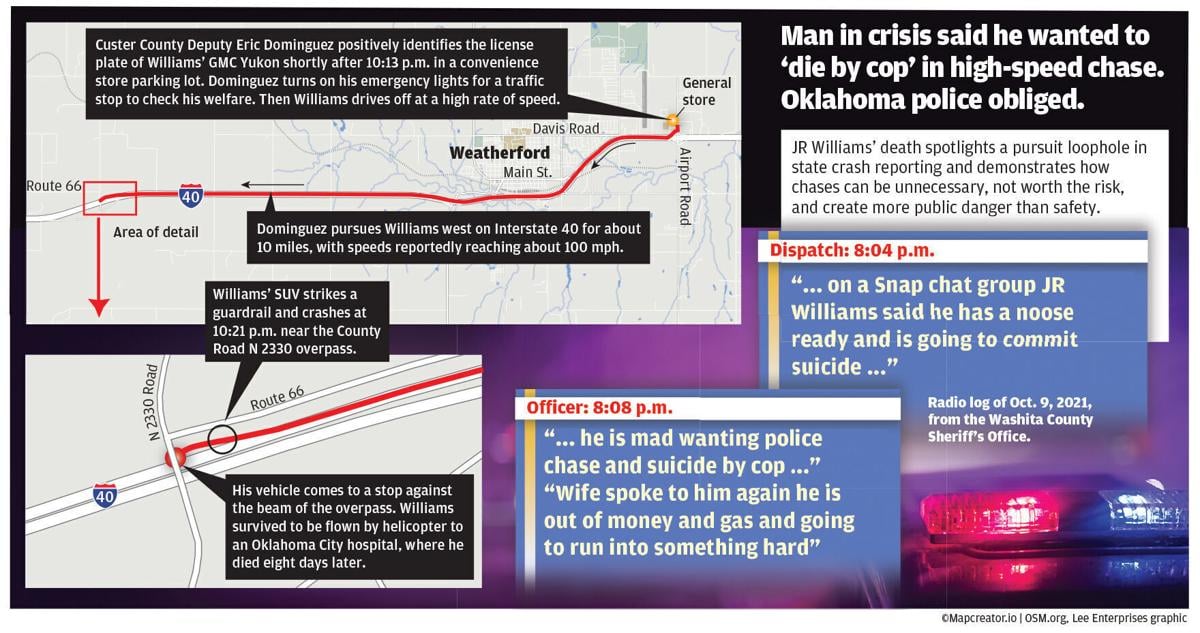

Custer County Deputy Eric Dominguez was advised to watch for a suicidal man in Weatherford who had told his family that he wanted to ŌĆ£die by copŌĆØ in a high-speed chase.

As J.R. WilliamsŌĆÖ phone ŌĆ£pingedŌĆØ nearby cell towers, a Washita County deputy provided Dominguez with location updates.

In a state ranked 8th highest for pursuit-related deaths, traffic infractions or property crimes prompted the vast majority of chases ŌĆö reasons not worth deaths or even pursuits, experts say.

An SUV ŌĆ£flashed its headlightsŌĆØ at Dominguez later that night at a convenience store. Unsure if he was being signaled, the deputy followed the 2004 GMC Yukon as it began leaving the parking lot.

The license tag matched that of WilliamsŌĆÖ. Dominguez activated his emergency lights to ŌĆ£check on the subjectŌĆØ who he knew was a risk to flee in a potential bid to be killed in a pursuit.

Only then did Williams start to drive off ŌĆ£at a high rate of speed,ŌĆØ according to police reports detailing the incident.

People are also reading…

Dominguez gave chase. Soon they were at about 100 mph on westbound Interstate 40 in west-central Oklahoma.

Williams crashed some minutes later ŌĆö deliberately, according to the investigation by the Oklahoma Highway Patrol, whose troopers had tried to slow WilliamsŌĆÖ vehicle with spike strips. The Highway PatrolŌĆÖs report says the 30-year-old man sped up after hitting the spikes.

Williams then struck a guardrail and an embankment before launching airborne into a bridge abutment. The damaged railing was flung into oncoming lanes of traffic.

He was airlifted from the scene that night of Oct. 9, 2021. He died eight days later at an Oklahoma City hospital.

ŌĆ£... during the pursuit Williams called (his family) to say his goodbye and that he was sorry,ŌĆØ Dominguez later wrote in a report of what a Washita County deputy had told him on scene.

A Tulsa World and Lee Enterprises Public Service Journalism investigation found that WilliamsŌĆÖ case spotlights a pursuit loophole in state crash data reporting that shields police pursuits from scrutiny. His death also illustrates how chases can be unnecessary, not worth the risk, and create more public danger than safety.

Law enforcement mishandled WilliamsŌĆÖ case, according to Mike Brose, who was CEO of Mental Health Association Oklahoma for nearly three decades. Brose, who still practices as a licensed clinical social worker in Tulsa, reviewed documents obtained by the World and Lee Enterprises.

Mike Brose

He said law enforcement had time to contact mental health partners and develop a safety plan rather than engage in a dangerous pursuit. He noted that Williams ŌĆö not reported to have been in possession of a weapon ŌĆö only threatened himself, hadnŌĆÖt committed a crime and had no significant outstanding charges.

ŌĆ£In my opinion, a much better approach would have been an alternative to the common law enforcement practice of ŌĆśyou run, we chase,ŌĆÖŌĆØ Brose wrote. ŌĆ£Both ends of his travel were covered from all reports.

ŌĆ£Patience and containment seems to have been a better tactical approach in this situation based on the knowledge law enforcement possessed.ŌĆØ

The Williams chase, which Brose said yields ŌĆ£much to teach and reflect onŌĆØ for law enforcement, was only found by the World and Lee investigation by examining raw autopsy data.

In a state with the eighth highest pursuit-related death rate, OklahomaŌĆÖs uniform traffic collision reporting form has no data element to track pursuits ŌĆö a dangerous police action on public roadways that often injures or kills people who arenŌĆÖt even the eluding drivers.

Former Oklahoma County Sheriff John Whetsel

Retired Oklahoma County Sheriff John Whetsel said the state needs to update its crash data collection program to include pursuit information to help reveal the causes and scope of the problem.

ŌĆ£As of right now, there is absolutely no way to measure the extent of the pursuit problem in this country,ŌĆØ Whetsel said. ŌĆ£We talk about the possibility of maybe 300,000 to 400,000 pursuits a year. I think itŌĆÖs going to be much higher than that.ŌĆØ

Whetsel advocates for better pursuit training and proper policies after in 1980. At that time, Whetsel was a local police chief who responded to the horrific wreck.

Reporting loophole

Law enforcement in three different fatality crash reports reviewed by the World and Lee failed to acknowledge in any way that a pursuit was involved.

In a few other deadly pursuits, law enforcement avoided using the words ŌĆ£pursuitŌĆØ or ŌĆ£chaseŌĆØ to describe what took place.

Only 11 of 68 collision reports of fatal police chases reviewed by the World and Lee noted in broad terms why the pursuits started.

The standard form is used by all policing agencies in Oklahoma to document wrecks to identify trends and improve public safety. But it has no designated method to specify when a crash involves a police pursuit.

Closing that loophole would open up a basic way to track Oklahoma pursuits and align with federally recommended reporting standards.

The National Highway Traffic Safety AdministrationŌĆÖs latest Model Minimum Uniform Crash Criteria (MMUCC) report published this year contains explainers for the first time on how to incorporate data elements to denote when police pursuits are a factor in a crash, as well as to identify pursuers and eluders.

ŌĆ£Oklahoma should update its collection program to include the current data points that NHTSA has incorporated into the crash data report ŌĆö as every state should,ŌĆØ said Whetsel, who was part of the effort to work with NHTSA to add pursuit data to the MMUCC standards.

Two agencies headquartered in the capital city reacted to growing chase deaths in opposite ways that might spur to action some lawmakers who have studied or regularly discussed pursuit issues.

The Oklahoma Department of Public Safety is transitioning agencies from its 2011 form to a report based on newer guidance that was issued in 2017.

New editions of the MMUCC have been put out in 2012, 2017 and 2024.

The Oklahoma Highway Safety Office (OHSO), a division of DPS, said it has applied for a federal grant to move to the 2024 reporting guidance ŌĆö what would be a five-year process if approved.

Megan Cardenas, OHSO communications manager, said the 2024 guidance hasnŌĆÖt been reviewed yet to determine which data elements might be added to the stateŌĆÖs collision reporting.

Cardenas stated that Commissioner of Public Safety Tim Tipton, who also oversees the Highway Patrol, has the authority to update the state collision report.

ŌĆ£There has not been a suggested change to the crash report since it was updated (in 2011),ŌĆØ Cardenas wrote. ŌĆ£There has not been a formalized process for this to occur, but one will be implemented in the new collision manual.ŌĆØ

Whetsel, who retired in 2017 after 20 years as Oklahoma CountyŌĆÖs sheriff, is a ŌĆ£huge supporterŌĆØ of every agency reporting crash and pursuit data to inform the public, lawmakers and agencies.

Better data collection would allow the agency, among other things, to identify problem officers and to remediate that behavior, Whetsel said.

ŌĆ£ThereŌĆÖs a lot of things that data provides to law enforcement agencies if they just use it,ŌĆØ he said.

Mental health crisis response

Police pursuits often receive much less attention and scrutiny than law enforcement shootings.

But the outcomes can be just as ŌĆö or even more ŌĆö deadly.

Custer County Deputy Shannon Greear observed that J.R. WilliamsŌĆÖ crash was so violent the guardrail was flung into oncoming lanes of traffic. She reported performing evasive maneuvers herself to avoid colliding with the damaged guardrails.

ŌĆ£With several vehicle (sic) still passing by the crash scene at high rates of speed, deputy (Evan) Tucker and myself raced to quickly remove the damaged guard from the oncoming traffic lane in attempts to help avoid another motor vehicle collision with the passing vehicles,ŌĆØ Greear wrote.

Custer County Deputy Eric Dominguez didnŌĆÖt report that Williams had done anything wrong when Dominguez tried to check on his welfare with a traffic stop.

Dominguez had been made aware that Williams intended to ŌĆ£die by copŌĆØ in a high-speed pursuit by Washita County Deputy Jason Maxey. Maxey was providing Dominguez with location updates as WilliamsŌĆÖ phone ŌĆ£pingedŌĆØ cell towers.

There is ongoing work across Oklahoma to help better respond to mental health crises without law enforcement, if possible.

Healthy Minds Policy Initiative is a Tulsa-based nonprofit that facilitates conversations among first-responders about best practices for responding to mental health crisis.

ŌĆ£It is genuinely better for somebody with a mental illness that a law enforcement officer does not respond if not necessary,ŌĆØ said Zack Stoycoff, the nonprofitŌĆÖs executive director, speaking generally. ŌĆ£It is genuinely better for the law enforcement officer to not be put in a position to try to be a mental health clinician.

ŌĆ£So thereŌĆÖs a win-win here, and that involves better mental health supports across the board.ŌĆØ

Zack Stoycoff.

Typically, Stoycoff said, a law enforcement response to a mental health situation would be to create scene safety, ensuring there isnŌĆÖt an immediate danger to the person or others.

Then, ideally, they would step aside and let a mental health practitioner work if there isnŌĆÖt a crime in progress or imminent threat of one.

Stoycoff said 988 ŌĆö a 24/7 suicide and crisis lifeline ŌĆö is available for police officers or anyone to dial for potential mental health situations.

Callers to 988 are connected with a counselor, who can offer help, guidance or services. That person also can determine whether a law enforcement response might be necessary and then summon officers.

Many officers in Oklahoma have direct lines to mental health providers, Stoycoff added.

ŌĆ£Nobody should be going into this conversation thinking, ŌĆśOh, thereŌĆÖs so few resources in rural Oklahoma. ThereŌĆÖs just no hope.ŌĆÖ ThatŌĆÖs not true. ThatŌĆÖs not true at all,ŌĆØ Stoycoff said. ŌĆ£We have more resources and more support for people in crisis and for our law enforcement partners than weŌĆÖve ever had in the history of this state. ItŌĆÖs a really exciting time.ŌĆØ

Corey Jones of Tulsa is a member of Lee Enterprises’ Public Service Journalism Team. corey.jones@lee.net