PHOENIX — State lawmakers convene Wednesday to weigh changes in an abortion law that dates from 1864.

But members of the first legislature, adopting the laws for the newly formed territory after it was separated from New Mexico, also were busy deciding what other kinds of things were legal and which were not. And while some have withstood the test of time, like statutes on homicide, others have become anachronisms or simply become unacceptable.

The bottom line is that the 441-page document finally adopted on Nov. 10, 1864 — 491 pages with various additions — and signed by territorial Gov. John Goodwin, included a few other things that might raise eyebrows today:

Declaring any marriage between a white person and a black person or mulatto performed in the territory to be null and void;

The age that a girl could legally consent to sex was 10;

People are also reading…

Challenging someone to a duel could land you in state prison for three years — five if the other person died.

And if the legal penalty is any indication of which crimes they considered the most severe, territorial lawmakers were apparently more interested in preventing gays from having sex than they were in protecting the unborn

That 1864 code said that “the infamous crime against nature’’ — something they left undefined but said that would be “either with man or beast’’ — required offenders to be sentenced to a minimum of five years in the territorial prison, “which may extend to life.’’ By contrast, performing an abortion, known as an act done “with the intention to procure the miscarriage of any women then being with child,’’ carried a minimum two-year prison term, with a maximum of five years.

It might also be noted that the infamous crime against nature actually remained on the books in ÃÛèÖÖ±²¥ statutes long into statehood. It was not until 2004 when it finally was repealed by state lawmakers at the behest of Republican Gov. Jane Hull. Legislators are removed laws against oral sex and cohabitation at the same time.

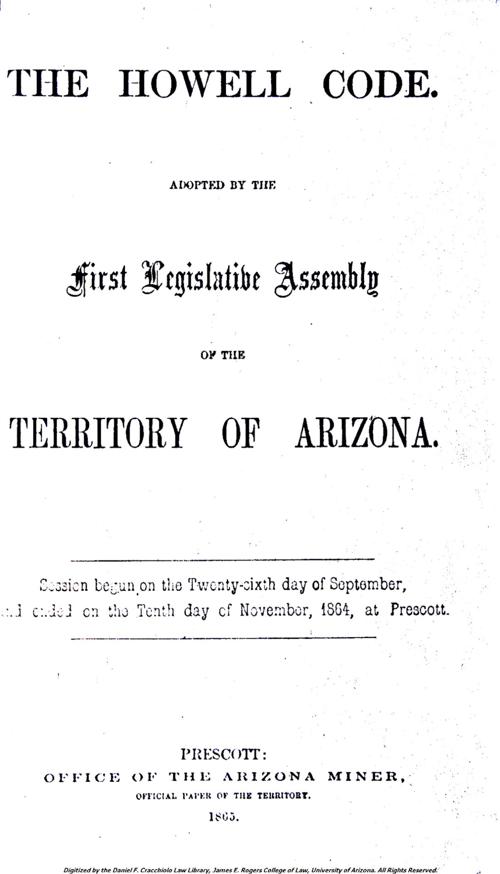

All of these provisions come from the Howell Code, named after William T. Howell who was the principal author of the territory’s first legal code. And Howell — and the territorial lawmakers who adopted his plan — had some other ideas when it came to men and women.

A married woman, for example, could not be found guilty of any crime punishable by death if she was “acting under the threats, command, or coercion of her husband.’’ In fact, the code spelled out that if that is the case, it would be the husband who would be prosecuted and punished as if he and not his wife had actually committed the act.

Male teens had to wait until 18 to get married without parental consent; for females, they could wed at 16.

Only white males 21 and older could be attorneys.

And disparities were not limited to gender.

“No black or mulatto, or Indian, Mongolian, or Asiatic shall be permitted to give evidence in favor of or against any white person.’’ And it went on to say any individual who was at least one-fourth ‘’of negro blood’’ would be considered a mulatto; for Indians, it took up to 50% of blood to be so classified.

All this extended to the right to vote, which was given to “every white male citizen of the United States and every white male citizens of Mexico, who shall have elected to become a citizen of the United States,’’ assuming they were 21. And voting was denied to any “idiot or insane person.’’

Yet in adopting the 491-page code, territorial lawmakers found themselves dealing with issues that still remain front an center.

Consider self-defense, an issue recently in ÃÛèÖÖ±²¥ headlines.

The statutes spoke of “justifiable homicide.’’ But there were limits, saying that “a bare fear ... shall not be sufficient to justify the killing.’’

There’s a provision for an annual census to determine how many senators and representatives each of the four counties at that time — Pima, Yuma, Mohave and Yavapai — can have.

But it also excluded Indians, Negroes and soldiers in military services. A 2024 proposal seeks to allow only citizens to be counted.

And, reflecting pending charges against a former president, there’s even a section making it a crime for an individual to obtain credit “by false representations of his own wealth.’’

Some other provisions, however, seem almost quaint by current standards.

Anyone older than 18 refusing to join a posse could result in a fine between $50 and $1,000.

And the laws also said that the state attorney general, aside from his salary — yes, they were all men at that time — was entitled a $50 fee for every murder trial in which the defendant is convicted. But that was reduced to $25 if there was no conviction.

A finding of guilt in a gambling case netted $20.

Yet prostitution remained legal into statehood.

Lawmakers in 1864 considering what should and should not be legal, also were concerned with some more petty things.

Disturbing the peace “at late and unusual hours’’ could draw up to two months in the county jail and a $200 fine. But if it involved two or more people, that called for up to six months behind bars for each and a $500 penalty.

Erecting a booth or tent to sell wine, beer or liquor within one mile of a religious camp meeting merited a $500 fine.

And libel, defined as malicious defamation by printing, signs or pictures, could draw a year in county jail and a $5,000 fine. That included both the author and the publisher.

But that law said that the jury could hear evidence during the trial, “and, if it shall appear to the jury that the matter charged as libelous is true, and was published with good motives, and for justifiable ends, the party shall be acquitted.’’

And despite provisions protecting white men, the nine senators and 18 representatives — including ÃÛèÖÖ±²¥ City resident José Redondo listed as a rancher born in Mexico — did adopt some statutes that could be considered fairly advanced, particularly as the Civil War was still being fought.

They made it a crime to hire, entice or seduce by false promises any “negro, mulatto or colored person’’ to leave the territory for the purpose of selling that person into slavery without that person’s “free will and consent.’’

They also recognized some rights of women — albeit not to vote or hold public office. That didn’t come until statehood and a 1912 initiative approved by the men who could vote for it by a 2-1 margin.

Under the Howell Code, any real or personal property a woman had when she got married remained hers and she could not be liable for debts of her husband. Conversely, a husband was not liable for debts incurred by his wife regarding her sole property.

The laws against bigamy and adultery also applied equally to men and women.

Illegitimate children were entitled to be considered an heir to his or her mother “and shall inherit her estate in like manner as if born in lawful wedlock.’’

And even the reasons for getting a divorce were equally applied.

While ÃÛèÖÖ±²¥ is now a no-fault divorce state, getting out of a marriage back then required something more, including adultery, desertion for more than two years, being sentenced to prison for more than three years or “when the husband or wife shall have become a habitual drunkard.’’

It also said if a husband is imprisoned for life, the wife was entitled to possession of all her real estate “in like manner as if her husband were dead.’’

In fact, the law even said that if either party is sent to prison for life, the marriage is “absolutely dissolved, without any decree of divorce or other legal process.’’

Yet in the case of adultery by the husband, gender mattered.

A judge dividing up property or awarding some financial settlement, could give it to the wife — or ordered it put into the hands of a court-appointed trustee who would be responsible for maintenance of the wife and minor children. And if it is the wife who is guilty of adultery “the husband shall hold her personal estate for ever.’’

Territorial lawmakers, like their more recent successors, also thought about the need for taxes. And while they recognized the need for revenues, they statutorily declared some items off limits to being taxes.

Household furniture, including stoves, were exempt up to $200 in value. So, too, were library and school books not exceeding $150.

And the laws were designed to ensure that no one was left without the ability to make do. The law exempted up to 10 goats or sheep — including their fleeces and the yard or cloth made from that — along with two cows, five swine, “and provision for the comfortable subsistence of such householder and family for six months.’’

Howard Fischer is a veteran journalist who has been reporting since 1970 and covering state politics and the Legislature since 1982. Follow him on X, formerly known as Twitter, and Threads at @azcapmedia or email azcapmedia@gmail.com.