The Star's longtime columnist compares the Pac-12 returning to football in the fall to jumping off a cliff. Plus, a look at other pertinent headlines in Southern УлшжжБВЅ sports this week.Ь§

A few miles outside of my northern Utah hometown is Hyrum Dam, a water-sports mecca with a captivating yet risky element that intrigued me and my friends for years.

At the south end of Hyrum Dam is тThe Thumb,т a 35-foot high cliff that became something of a right of passage for teenagers. If you had not jumped off тThe Thumbт by the time you were 18, you were, to put it politely, тsoft.т

There have been deaths and drownings. There have been broken legs and broken necks.

But in the summer after my senior year in high school, I joined four friends at тThe Thumb.т We all tiptoed to the edge of the cliff, staring over the edge, nervous, absorbing the risk. To get to the water, one had to sprint 10 or 15 yards т a blind jump т to reach water deep enough to avoid injury.

People are also reading…

We stood and stared for what seemed like forever; we all knew that if one of us summoned the courage to jump, we must follow. Finally, my friendЬ§Greg ThorpeЬ§said something like тI hope I donтt regret this,т backed up, sprinted 15 yards and screamed loudly as he left safe ground.

A few minutes later, four of us were in the water. None of us ever attempted the jump again.

I get the feeling that a latter-dayЬ§jump off of тThe Thumbт was part of the process that led the Pac-12 and Big Ten to reconsider their decision not to play football in the fall of 2020.

The desire for normalcy, compounded by impatience and the chance to alleviate financial stress and save jobs т as well as the human nature of not wanting to be left behind т overcame the inexactness and medical ambiguity of playing college football.

There is little doubt that the Pac-12 this week will announce a return to football with a six-game schedule beginning Nov. 7. Everyone in the water.

The Pac-12тs decision will walk back its early August declaration to follow safety and science and not risk the health of those on their campuses. In retrospect, itтs somewhat hard to believe that UCLA, USC, Cal and Stanford т the leagueтs power brokers т are now aboard the letтs-play-football train.

Stanford is Stanford. If the Cardinal plays football or not, it really doesnтt matter. It will still be Stanford, a separate and powerful institution of one.

Cal is driven by academics. Itтs in Berkeley, which in a lot of ways is still in the Haight-Ashbury hippie days of the 1960s and 1970s. Football is not king. Not even close.

UCLA has a new athletic director, who has yet to be more than a commuter newbie to campus. UCLAтs president has announced his retirement. Whatтs more, school has not yet begun at UCLA, which operates on the quarter system.

USC has a new president and first-year AD. The areas in and around USC and UCLA has all but been paralyzed by COVID-19.

You could see Californiaтs wait-until-spring decision coming from 100 miles away.

Others in the league т notably Utah, Colorado, УлшжжБВЅ, ASU, Oregon and Oregon State т believed much earlier that playing football could be safe with the rapid-results testing the league engineered a few weeks ago. The California schools balked. But thereтs more to it than that.

Had УлшжжБВЅ, ASU and their partners chosen not to return to fall football, three things were likely to happen:

1. Each athletic director and football coach wouldтve had a line of players т the тopt-outsт т at the door seeking a transfer waiver, saying something like тI want to play somewhere that football is important.т

2. The already-struggling reputation and brand of Pac-12 football wouldтve taken a punch like no other. Those in the SEC, Big 12 and Big Ten wouldтve raided the Westтs recruiting Classes of 2021 and 2022. The Pac-12тs status as a Power 5 football conference wouldтve been further diminished. Its future media rights negotiations wouldтve suffered.

3. It wouldтve been difficult for ADs to look their coaching staffs in the eye and tell them why they should decline an offer to coach at, say, Kansas State or Illinois, even the mid-level schools in football-centric conferences.

By returning to action Nov. 7, or perhaps Oct. 31, each Pac-12 school should be able to realize its full media rights financial package and keep most of those in the department employed.

The media rights contracts with ESPN and Fox require 45 telecasts each football season. That can yet be fulfilled. Each game on ESPN/Fox is worth close to $5 million to the league. Do the math. Jobs can be saved.

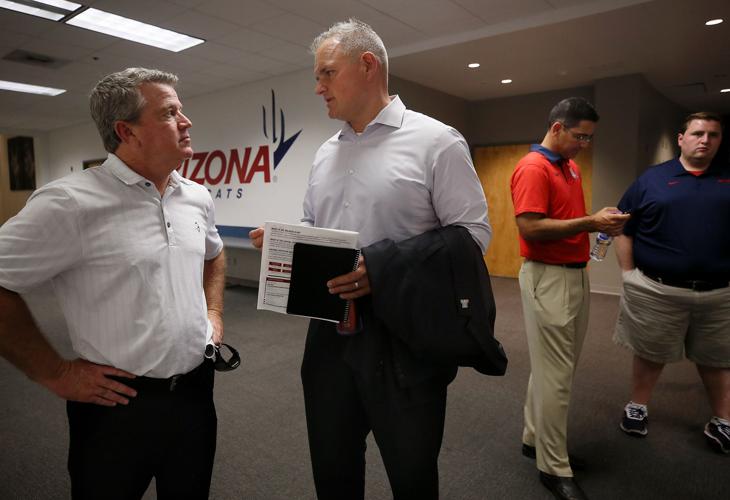

Dave Heeke, director of athletics at the University of УлшжжБВЅ, speaks during the dedication of Dick Tomey Football Practice Field at the University of УлшжжБВЅ, on Nov. 1, 2019.

УлшжжБВЅ athletic directorЬ§Dave HeekeЬ§is not yet sure fans will be allowed at УлшжжБВЅ Stadium in November and December. Those decisions are fluid; plus, if only 5,000 or 8,000 fans are permitted inside the stadium, it might cost more for operational costs than what would be made by ticket sales. Travel т hotels and flights т will not only be risky, but very expensive in the environment of 2020.

As it now stands, УлшжжБВЅтs football team can train about 12 hours a week. Most of it is strength and conditioning related, or тpracticing against air.т

If the Pac-12 this week declares it is open for football, the UA would have about two weeks of rampܧup preparation, followed by a traditional four-week training camp.

Many will be critical of the Pac-12 being the last Power 5 league to commit to football, but it had far more to overcome than its peers, with the California тissueт being foremost.

A few weeks ago, UA presidentЬ§Robert C. RobbinsЬ§said тthis isnтt a gameт when speaking of on-campus students who were not observing safety protocols. College football is no longer a game, either. Five games were postponed this weekend because of health issues.

Itтs not teaching a med student how to perform heart surgery, and itтs not teaching a pre-law candidate immigration laws.

Given all the risks at play, itтs going to be like jumping off a cliff.

Terry Francona, Jim Furyk set the longevity pace

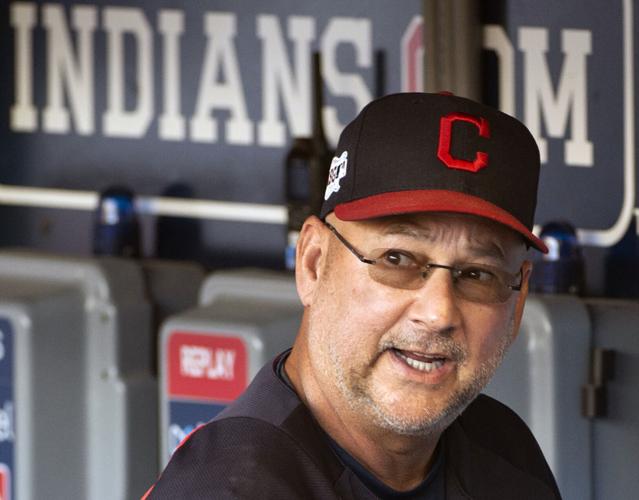

Terry Francona managed the Phillies and Red Sox, winning two World Series titles in Boston, before agreeing to take over the Indians.

УлшжжБВЅтsЬ§Terry Francona, УлшжжБВЅтs 1980 NCAA baseball player of the year, has missed most of the baseball season with gastrointestinal and blood-clotting issues; for the last six weeks, the Cleveland IndiansЬ§manager has been replaced by assistant coachЬ§Sandy Alomar Jr.

This is Franconaтs 30th year either as a major-league player or manager/coach, which is a longevity record for the approximately 300 former UA/УлшжжБВЅ athletes who reached MLB, the NBA, NFL or played on the PGA Tour. Next? ItтsЬ§Jim Furyk, who is on his 27th year on the PGA Tour, although Furyk this weekend is missing his first U.S. Open since 1996.

Hereтs the leaderboard, which should give you an idea of how difficult it is to find lifelong employment at the highest level of pro sports:

1. Francona, 30 years

2. Furyk, 27 years

3.Ь§Steve Kerr, basketball, 21 years

4.Ь§Chip Hale, baseball, 21 years

5.Ь§Ron Hassey, baseball, 20 years

6.Ь§Chuck Cecil, football, 20 years

7.Ь§Brad Mills, baseball, 20 years

8.Ь§Jason Terry, basketball, 19 years

9.Ь§Brant Boyer, football, 19 years

10.ܧLuke WaltonܧandܧJud Buechler, basketball, 16 years

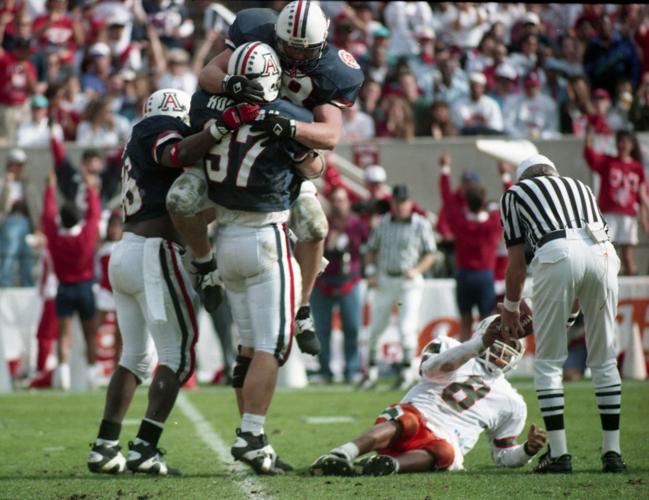

Boyer, a former UA linebacker from the тDesert Swarmт era, is working his 19th year in the NFL. He is the most unlikely of the above. He is now in his fifth year as part of the New York Giants coaching staff. He previously worked four years for the New York Jets, and played 10 NFL seasons.

Boyer played at small-school North Summit High School in northern Utah. He was a walk-on at Snow College beforeЬ§Dick TomeyЬ§spotted him in 1991 and signed him to play at УлшжжБВЅ. Boyer was the equivalent of a one-star recruit.

УлшжжБВЅ tackle Jim Hoffman is congratulated by teammates Brant Boyer and Akil Jackson after sacking Miami QB Ryan Collins during the 1994 Fiesta Bowl in Tempe, Ariz.

Heтs so much like his father, my college classmate, who was a starting cornerback at Utah State in the 1970s. Too small. Too slow. All he could do was help you win. After Boyer somehow survived 10 NFL seasons with limited size and speed, he moved to Colorado and became an outdoor hunting/fishing guide for five years before he was coaxed back to the NFL by one of his former NFL coaches,Ь§Chuck Pagano.

I noticed Boyer during the national anthem of last weekтs Giants game. He stood at attention with his hand over his heart. His face showed emotion. I remember meeting his grandfather,Ь§Edwin Boyer, while at a Utah State game in the 1970s. A mink rancher from a rural Utah town, he talked about his days as a Marine in World War II. He was almost killed at Iwo Jima and was so proud of his son т Brantтs father т who had become a starting college cornerback.

Fortunately, Edwin Boyer lived long enough т he died last winter at 94 т to see his grandson become an accomplished NFL coach.

Only sevenܧex-UA players sustained NFL careers longer than Boyer. They are:

1.Ь§Tedy Bruschi, linebacker, 13 seasons

2.Ь§Lance Briggs, linebacker, 12 seasons

3.Ь§Nick Folk, kicker, 12 seasons

4.Ь§Josh Miller, punter, 12 seasons

5.Ь§Glenn Parker, tackle, 12 seasons

6.Ь§John Fina, tackle, 11 seasons

7.Ь§Chris McAlister, cornerback, 11 seasons

Some perspective: UA linebackerЬ§Scooby Wright, the Pac-12тs defensive player of the year in 2014, played in 13 NFL games over two seasons. He is now at the start of a two-year process to become a firefighter. Getting to the NFL is hard. Staying in the NFL is harder.

УлшжжБВЅ's Derek van der Merwe on CMU's hot list

Derek van der Merwe, center, is the new chief operating officer, at the University of УлшжжБВЅ. July 26, 2018.

Derek van der Merwe, the UAтs athletic departmentтs Chief Operating Officer, is one of three finalists to become the athletic director at his alma mater, Central Michigan University.

Van der Merwe is expected to learn this week if he gets the job; the other finalists includeЬ§Amy Folan, the No. 2 person in the Texas Longhorns athletic department, andЬ§Alan Haller, the deputy athletic director at Michigan State. It would be a surprise if van der Merwe isnтt hired. He played football at CMU from 1991-95, and was co-captain of the team.

Whatтs more, van der Merwe then worked every conceivable job in CMUтs athletic department т including five years under then-CMU ADЬ§Dave HeekeЬ§т before becoming the AD at Austin Peay.

тDerek is incredible; Iтd hate to lose him,т said Heeke. тThe depth and breadth of his experience, across the board, is so impressive. Heтs got a lot of connections at Central Michigan.т

Van der Merwe has been the No. 2 person on Heekeтs staff for 2Ц years. There is history involved; the No. 2 man underЬ§Cedric DempseyЬ§at УлшжжБВЅ,Ь§Bob Bockrath, left УлшжжБВЅ to become Calтs AD, and later the AD at Alabama and Texas Tech. The No. 2 person under УлшжжБВЅ ADЬ§Jim Livengood,Ь§Chris del Conte,Ь§became the AD at TCU and now Texas; and the No. 2 man underЬ§Dave StrackЬ§in the 1970s,Ь§Bill Belknap, left УлшжжБВЅ to become the AD at Idaho and later Wichita State.

Wildcats lose sprinter to Texas A&M

James Smith

УлшжжБВЅтs track team has lost one of its most valued performers, sophomore sprinter/hurdlerЬ§James Smith, who has transferred to Texas A&M. As a freshman in 2019, Smith finished fifth in the NCAA in the 400 hurdles, was a first-team All-American who won the USATF championship in the U-20 nationals and was second in the Pan American Games. UA coachЬ§Fred HarveyЬ§recruited Smith out of Westwood High School in the greater Phoenix area.

Charlie Dickey declines to take pay cut at Oklahoma State

Former УлшжжБВЅ offensive lineman and longtime UA assistant football coachЬ§Charlie DickeyЬ§last week was part of an Oklahoma State coaching staff asked to take a 40% pay cut to help the financially embattled OSU athletic department. Dickey is paid $550,000 per year. He and the other assistant coaches declined to take the cut, according to Oklahoma newspapers. Another former UA assistant coach,Ь§Kasey Dunn, who is paid $800,000 a year as OSUтs offensive coordinator, was also part of the group that declined staff-wide reductions. It was not a good look; but because the football coaches did not have тact of Godт clauses in their contracts, they could not be forced to take a pay cut. The Oklahoman reported that they offered to take a smaller percentage pay cut, but could not reach an agreement with the athletic department.

Pima hoops teams could soon return to gym

Pima coach Todd Holthaus celebrates after his team won the regional title game over Mesa Community College, earning the Aztecs a spot in the NJCAA Division II National Tournament.

УлшжжБВЅ women's golf team attracts Thailand starЬ§

UA womenтs golf coachЬ§Laura Ianello, winner of the 2018 NCAA championship, has not been inactive during the shutdown of college sports. Last week she got a commitment fromЬ§Pimmada WongthanavimokЬ§т she goes byЬ§Nena WongЬ§т of Thailand. That fits with Ianelloтs rise to the top of NCAA womenтs golf; her returning roster in 2021 includes world No. 2 womenтs amateurЬ§Vivian HouЬ§and her sister, No. 41-rankedЬ§Yu-Sang HouЬ§of Taiwan, and No 54Ь§Ya Chun ChangЬ§also of Taiwan. Wong, who is a high school junior, has already won international amateur titles at the Albatross International Juniors in India, and the World Stars of Junior Golf championship in Las Vegas.

Former UA football players to cook for 'tailgate'

Chuck and Carrie Cecil took part in the "Cooking With the Stars" in 2020. Chuck's cooking skills will be put to the test again with other УлшжжБВЅ greats.Ь§Ь§

Although no football game will be played, a dozen former УлшжжБВЅ football players will be part of a тFlying Aprons Cooking Tailgate Eveningт from 5:30-7 p.m. Friday via Zoom conference.

Salpointe Catholic High School and UA gradܧJohn Fina, a long-time NFL lineman, will act as chef, cooking from his home with sous chefsܧChuck CecilܧandܧLamont Hunley. Former Wildcat football playersܧOrtege Jenkins,ܧJoe Tafoya,ܧByron Evans,ܧTrung Canidate,ܧEarl Mitchell,ܧRandy RobbinsܧandܧBrandon Sandersܧwill be among those participating in the socially distanced Zoom event. To register for the virtual tailgate party, email:ܧflyingapronstucson@gmail.com

My two cents: Time to give UA docs like David Harris a raise

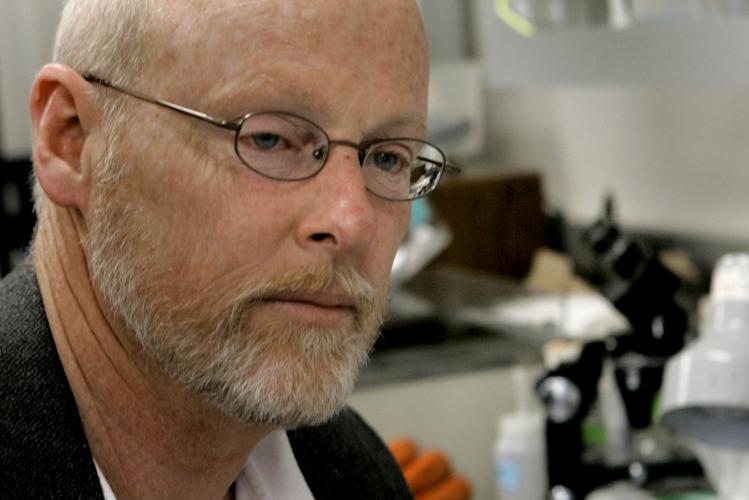

Dr. David T. Harris, executive director of the UAтs Health Sciences Biorepository, says he trusts Quidelтs product. The UA has administered more than 25,000 tests since the spring.

Much of the reason the Pac-12 is expected to announce it will resume football in early November is because УлшжжБВЅ has conducted more than 25,000 Quidel tests on students, athletes, staff members and ICU patients since spring. Quidel is a rapid-response antigen test; it will be delivered to all Pac-12 teams this month.

Dr.Ь§David HarrisЬ§oversees the program. In a UA perspective, Harrisт work is something like УлшжжБВЅ winning a Rose Bowl т but better.

Harris, who played football at Wake Forest from 1974-78, is the executive director of the UAтs Biorepository program, a division of Translational and Regenerative Medicine. He has been conducting his remarkable work at the UA Health Sciences Center for 31 years. Not only that, Harris has founded five companies as they relate to biobanking and immunobiology.

Hereтs my point: according to the UAтs 2018-19 salary database, Dr. Harris is paid $177,448 annually. Given the value of Harrisт work, shouldnтt his compensation include a few more digits or another comma?

In an era when college sports salaries have gotten twisted out of common sense т the UAтs two receivers coaches in football were paid $235,000 and $200,000, respectively, last season т the COVID-19 pandemic shows just head-shaking the salary structure of college sports has become.