After the 2020 La Fiesta de los Vaqueros, the ÃÛèÖÖ±²¥ Rodeo Committee donated $250,000 to various ÃÛèÖÖ±²¥ charities.

Much of that money was made available by an average attendance of close to 8,000 at the ÃÛèÖÖ±²¥ Rodeo Grounds, and much more was generated via sponsorship from the top names in pro rodeo: Justin Boots, Wrangler jeans, Dodge truck and Bailey cowboy hats.

On the day Gary Williams became part of the ÃÛèÖÖ±²¥ Rodeo Committee in 1985, a volunteer who helped park cars, the historic rodeo did not have any sponsors or signage at the rodeo grounds.

They didn’t even sell beer; fans could bring their own six-pack to the arena. Even though it had been in business since 1925, one of the top 20 or 25 rodeos among about 650 pro rodeos every year, La Fiesta de los Vaqueros struggled to break even financially.

That all began to change when Williams, a rodeo lifer from Rincon High School, a bull rider and rodeo clown who had spent five years as director of operations for the ÃÛèÖÖ±²¥-Sonora Desert Museum, became the ÃÛèÖÖ±²¥ Rodeo Committee’s first general manager in 1995.

People are also reading…

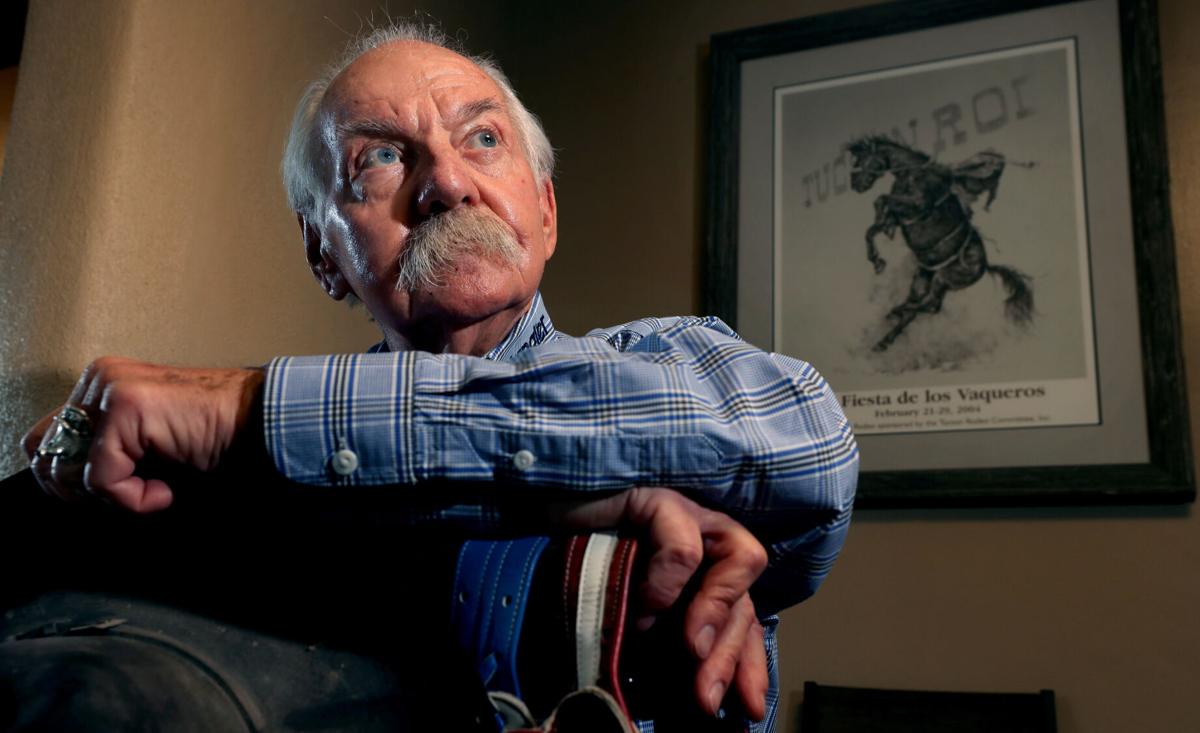

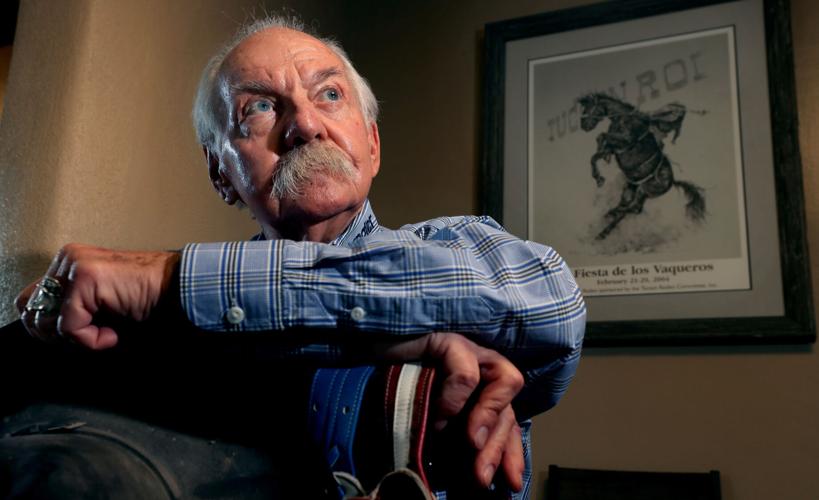

Williams, who is No. 59 on our list of ÃÛèÖÖ±²¥â€™s Top 100 Sports Figures of the last 100 years, was the face of ÃÛèÖÖ±²¥â€™s PRCA event for a quarter century before retiring in December 2020.

It wasn’t a job to him.

“For me, the saddest time is 5 o’clock on Sunday afternoon when the rodeo is over,’’ he said. “I’d just as soon start slack again on Monday morning.’’

He described his long tenure on the ÃÛèÖÖ±²¥ Rodeo Committee as “a wonderful life.’’

If you could get the energetic Williams to stop long enough for a sit-down conversation, you might notice that he wore a ring fashioned as a saddle. It was the ring his father, Gene, a rodeo man to the core, wore when he introduced his son to rodeo.

Gene Williams, a musician for notable Western bands in Southern ÃÛèÖÖ±²¥ who worked for the Southern Pacific Railroad, bought Gary his first horse — “Rebel" — when he was 4.

“For me, the saddest time is 5 o’clock on Sunday afternoon when the rodeo is over,’’ said Gary Williams. “I’d just as soon start slack again on Monday morning.’’

“The ring was a symbol of what my dad wanted to be,’’ Williams said. “He wanted to be a cowboy."

Gary’s mother, Audrey, who was front and center at every ÃÛèÖÖ±²¥ rodeo for almost 30 years before she died two years ago, had also grown up steeped in rodeo tradition.

The Williams family was so tied to the rodeo community that when iconic cowboys Jim Shoulders and Casey Tibbs competed in La Fiesta de los Vaqueros, they connected with Gene Williams and spent time in the family’s midtown house.

To young Gary Williams, it was like a baseball fan seeing Joe DiMaggio and Mickey Mantle in the living room.

Once Williams became part of the rodeo committee, he moved to make it sustainable as prize money and production costs soared.

“The real rodeo fans here, we couldn’t live without them," he said. “God bless ‘em, they’re wonderful folks. But if we had to depend on them, we’d all starve. There are not just enough of them."

Before he retired, Williams was one of the most recognized faces on the PRCA calendar. He was chosen to be part of the executive committee of the National Finals Rodeo every December in Las Vegas, where his ever-present cowboy hat and western-style mustache made him one of the most identifiable figures in the rodeo industry.