Two groups of researchers at the University of УлшжжБВЅ are spearheading projects to save lives by developing new tools for detecting gynecologic cancers.

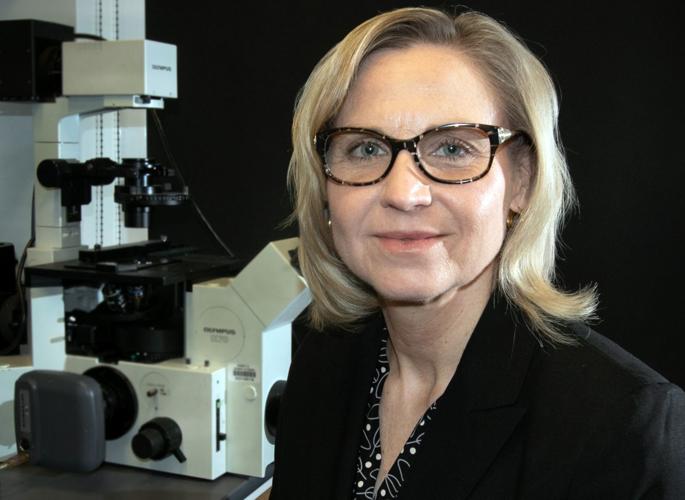

Jennifer Barton, director of the Bio5 Institute and UA professor, received a three-year $863,000 grant from the Army to create a disposable endoscope that can weave its way into and get a clear image of the fallopian tubes, where the most lethal and most common forms of ovarian cancer originate.

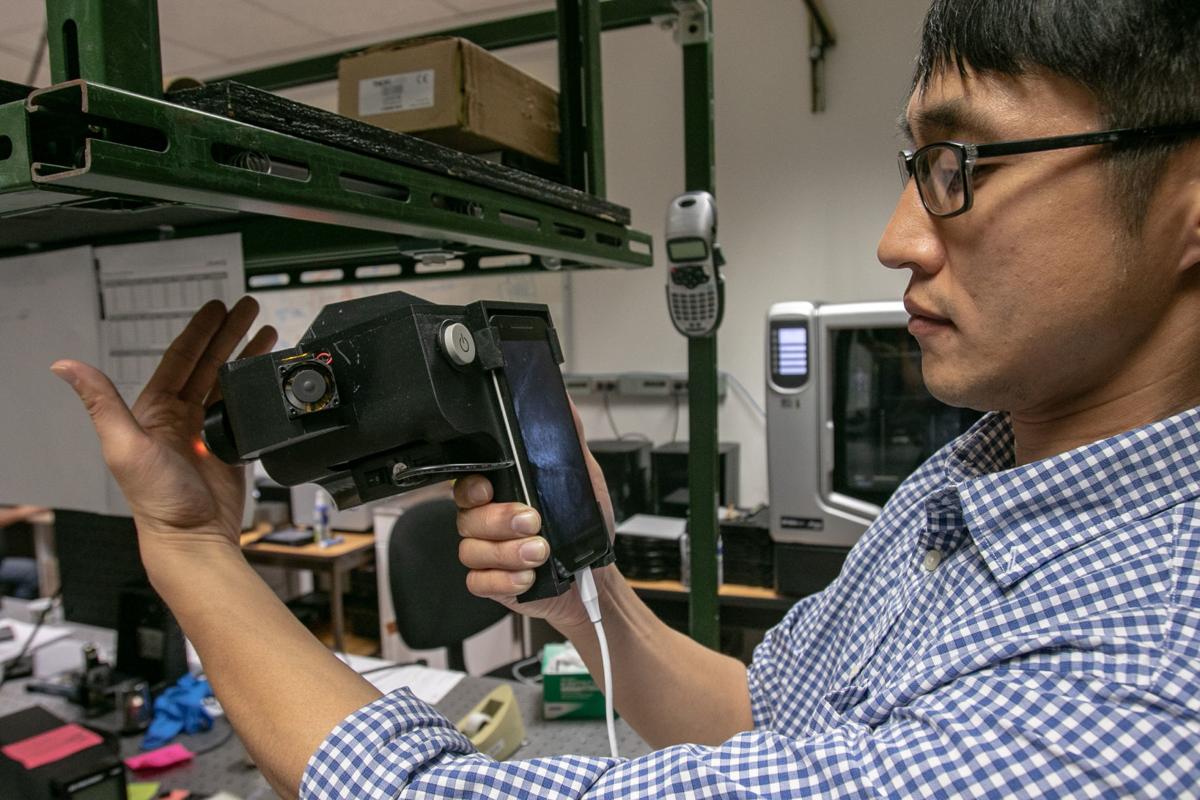

The John E. Fogarty International Center granted Dongkyun Kang, assistant professor in the department of biomedical engineering and the College of Optical Sciences, $400,000 to develop an endoscope that can be attached to a smartphone to detect cervical cancer in Ugandan women living in rural areas.

тIтm tired of my patients dyingт

In 2018, about 22,240 women will receive a new diagnosis of ovarian cancer in the United States, and about 14,070 women will die, according to the American Cancer Society.

People are also reading…

It is the eighth most common cancer in this country and the fifth-leading cause of cancer death, reports the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Most women who get cervical cancer are over 40 years old, with the majority in their 60s.

Ovarian cancer can be so lethal because it often goes undetected in the fallopian tubes for years. Once it ventures into the ovaries, it develops into late-stage cancer quickly, Barton said. It is rare that the disease is found early.

When Barton was working toward her Ph.D. in biomedical engineering, she was studying how light interacts with human tissue and how light can be used to diagnose and treat different diseases.

тI met a gynecologist who said, тYou have to solve ovarian cancer because Iтm tired of my patients dying,тт Barton recalled.

That was about 15 years ago. тItтs a really hard problem,т she said. Sheтs been working on the solution on and off for all that time, but the technology has finally caught up with her ambitions.

With an $863,000 Army grant, professor Jennifer Barton will be able to make her endoscope prototype patient-ready.

Tube tech

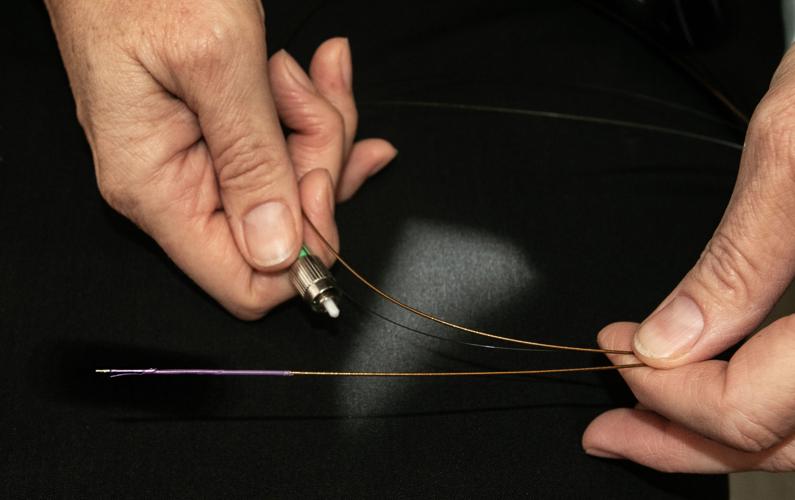

тFallopian tubes are difficult to reach because at the point they attach to the uterus, theyтre only about a millimeter in diameter. Our endoscope is 0.8 millimeters in diameter,т Barton said. Making an endoscope that small, with fiber optics that tiny, would have been impossible 15 years ago, she said.

The endoscope is made of flexible plastic that is safe to enter the body. The fiber optics go inside along with тteeny tiny wires you can pull and steer,т she said.

When exposed to certain kinds of light, body tissue glows differently in health and disease. Barton and her team should be able to visualize any cancer or pre-cancer when peering into the fallopian tubes.

She has a prototype in her lab, but the grant will go toward making the device patient-ready and will fund the human tests.

Current screening methods for ovarian cancer, which include transvaginal ultrasounds and a certain blood test, are not reliable enough for average-risk women to be screened.

Based on current evidence, these screening tests have the mortality of ovarian cancer and can lead to over-diagnoses, the detection of nonlethal cancers and false positives, said Dr. Barry Kramer, director of the division of cancer prevention at the National Cancer Institute.

When average-risk women are screened, they might undergo unnecessary surgery to remove their ovaries and suddenly find themselves dealing with the symptoms of postmenopause.

Only women with a high risk for the disease are encouraged to screen. These women either have a family history of the cancer or a specific genetic mutation.

For a screening test to be considered successful, the total harm must outweigh the total benefit to a patient. Barton hopes that soon a more effective blood screening test will be developed and her technology can be used to confirm the results, as it is too invasive to use as the first line of detection.

With the grant money, Barton and her team will build a fully functional falloposcope т an endoscope for the fallopian tubes. She hopes to start testing on real women in early 2020.

Women who have volunteered to participate in her trial are already having their fallopian tubes removed, so there is minimal risk to them.

тTheyтll be ready. We go in. We image them, and we leave,т Barton said. The removal of the fallopian tubes can resume. For patient privacy, she and her team will never know the participantsт identities. The physician acts as her teamтs connection with the patient.

тThere have been a lot of women who have helped me in my research, and I donтt know who they are, and I thank them,т Barton said.

Jennifer Barton, head of the Bio5 Institute, holds a prototype of an endoscope for the fallopian tubes, which are difficult to reach. She hopes to start testing on women in early 2020.

Circumventing cervical cancer

Compared to ovarian cancer, cervical cancer in the United States is much more manageable.

тEver since we achieved the breakthrough of cervical cancer screening (via Pap smears) ... mortality rates have dropped dramatically,т Kramer said. HPV vaccines have driven down the rates of cancer even further.

Unfortunately, thatтs not the case in poorer countries. тWe know how to achieve the same thing, but they donтt have the infrastructure, wealth or professional resources to do what we do,т Kramer said.

And thatтs just the first line of screening. Follow-up methods and treatments are even more expensive and intensive, said Kang, who is also a member of the Bio5 Institute and the UA Cancer Center.

Without these tools, the cancer isnтt being caught early enough in these countries, and far too many women die of this тpreventableт disease, as the CDC puts it.

Across Africa, 34 out of 100,000 women are diagnosed with cervical cancer and 23 out of every 100,000 women die every year. In North America, seven out of 100,000 women are diagnosed and 3 out of 100,000 die, according to the World Health Organization.

With all that in mind, Kang had an idea to take those resources to rural communities in Uganda.

Smartphones are powerful. In one palm-sized machine you have a light source, a light detector and a computer, Kang said.

тIтve always been fascinated with the image quality that you get (from smartphones),т he said. тThatтs why I came to like the idea of using it for medical purposes.т

He is trying to produce a device that can attach to a smartphone that will image cancer and pre-cancer cells at varying depths in the cervical wall, like an ultrasound, he said, but at the microscopic level.

He also wants to be able to treat any cancerous or precancerous regions during the same visit by freezing and killing the diseased tissue.

This is important because itтs difficult for women in rural areas to make the trek to a health clinic.

тIf you can screen and treat on-site, it will almost certainly save a lot of lives,т Kramer said.

The first year of the grant will be spent building the device and the second will be spent rolling it out across Uganda, Kang said. He hopes the technology will cost about $3,000.

His ultimate goal is to develop machine-learning software that can diagnose the presence of cancer so that even less-trained health workers can use the device.

Kang worked at Massachusetts General Hosptial for 11 years developing endoscopes but said he was drawn to the UA for its focus on translating lab work to real-world solutions.

тWhen you see how all your technology really impacts human lives, itтs compelling,т Barton said.