Radiocarbon dating was invented 70 years ago with a little help from the University of УлшжжБВЅ, and the scientific breakthrough just keeps improving with age.

A worldwide working group of researchers, including some in УлшжжБВЅ, recently unveiled a newly refined radiocarbon scale that extends the reach and the accuracy of the dating process.

Scientists can now use what they know about past levels of radioactive carbon-14 in the environment to determine the age of organic material from the past 55,000 years, all the way to the approximate limit of the dating technique.

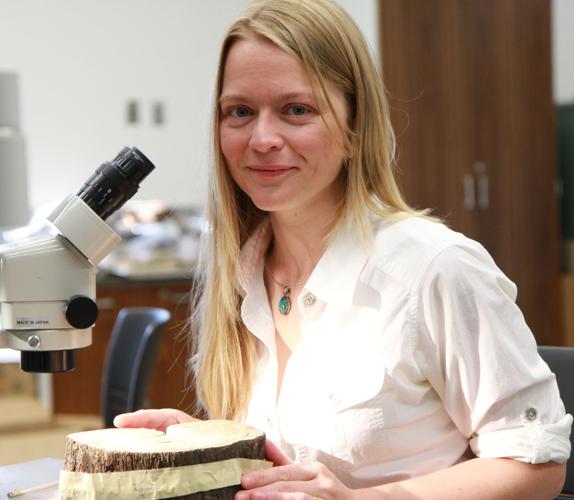

тItтs probably the most worthwhile thing Iтve been involved in in my career,т said working group member Charlotte Pearson, an assistant professor of dendrochronology, anthropology and geosciences at the UA. тIтm part of something that feeds back into the entire system. Anyone dating anything from the past (55,000) years will be using this resource.т

People are also reading…

Radiocarbon dating can be used to determine the age of old bones and artifacts or study climate conditions thousands of years ago. It works by assessing the ratio of different kinds of carbon atoms in an object and comparing it to the amount of those same isotopes in the atmosphere.

Because atmospheric carbon levels differ around the world and have fluctuated throughout history, scientists need a reliable historical record of these variations so they can translate their carbon measurements into calendar ages.

Thatтs where the international radiocarbon calibration curves come in. They provide researchers with three agreed-upon scales of atmospheric carbon levels through time т one for the Northern Hemisphere, one for the Southern Hemisphere and one for the worldтs oceans.

Those scales are recalculated and adjusted every decade or so to reflect the latest findings.

тIt kind of evolves with the technology,т Pearson said.

A тrevolutionaryт way to study the past

This marks the first time the curves have been updated since 2013.

The work was done by more than 40 researchers from labs and universities around the globe. Their findings are based on measurements from cave formations, lake-bed core samples and the growth rings of trees, as well as 15,000 samples from objects dating back as much as 60,000 years.

тItтs the sort of project in science that needs input from a lot of different experts,т Pearson said. тItтs definitely the best version of the curves yet.т

University of Chicago professor Willard Frank Libby pioneered radiocarbon dating in 1949. The Manhattan Project veteran tested his groundbreaking new technique using samples from the UAтs tree-ring lab, which was housed inside УлшжжБВЅ Stadium back then.

тItтs been really revolutionary for how we study the past,т Pearson said. тWeтve gotten used to hearing that something is 8,000 years old or 10,000 years old. We kind of take it for granted.т

By the time Libby was awarded the Nobel Prize for Chemistry for his discovery in 1960, more than 20 carbon-dating labs had been established worldwide, including the one at the UA.

UA plays major role in radiocarbon science

The local radiocarbon connections do not end there.

UA geosciences professor Timothy Jull said the university hosted the first meeting of the calibration working group in 1980, and УлшжжБВЅ researchers were intimately involved in the development of the first international scale for radiocarbon dating in 1986.

Before that, scientists used their own favored dating scales, leading to arguments and a fair bit of confusion. Jull compared it to trying to fly an airplane using a bunch of different altitude estimates.

This is the seventh calibration he has taken part in since he joined the UA in 1981.

тItтs a huge international project,т Jull said. тMany of these people have been doing this for 20 or 30 years.т

He said the new curves are тa significant improvementт over the old ones, thanks to recent advancements that have made it quicker and easier to collect radiocarbon measurements with previously impossible precision and detail.

Where tree-ring work used to require large slabs of material, scientists can now tease the information they need from single growth rings on tiny slivers of wood.

The resulting surge in data has pushed the time scales in one direction or another by a few decades in some cases and a century or more in others, providing new, more accurate estimates for landmark historical events.

Pinpointing eruptions, other тbig-signalт events

Pearson and her research team can vouch for that. They recently used more refined radiocarbon data from annual tree rings to narrow in on the long-debated date of the ancient Thera volcano eruption on the Greek island of Santorini.

The Bronze Age blast was one of the largest eruptions humanity has ever witnessed, and Jull said the findings by Pearsonтs team place it closer to the 1540 B.C. estimate favored by archaeologists. Those measurements are now reflected in the newly calibrated radiocarbon scales.

Jull said the new curves also provide a more accurate date for what he called a тbig-signal eventт roughly 41,000 years ago, when the Earthтs magnetic field collapsed and then came back.

Traces of that event show up throughout the scientific record, so getting a more precise fix on when it happened is important.

тItтs used as a marker for all sorts of things,т he said.

The updated calibrations were released Aug. 12 in three separate papers published in тRadiocarbon,т a УлшжжБВЅ-based scientific journal put out by the UAтs Department of Geosciences in partnership with Cambridge University Press.

The new and improved curves have since been added to several major online carbon-dating calculators, so researchers around the world can start using them right away.