Raytheonтs УлшжжБВЅ-based missile unit stands to gain billions of dollars in the next few years for development of a new air-launched, nuclear cruise missile.

Raytheon Missiles & Defense recently won a $2 billion Air Force contract to take the next step in developing the Long-Range Standoff Weapon or LRSO, in a program expected to be worth some $10 billion to the company over time.

By around 2030, the LRSO is expected to replace the AGM-86B Air Launched Cruise Missile, the latest version of the nuclear-capable missile used since the 1980s.

Though many program details remain classified, the LRSO is expected to have the latest in radar-evading stealth technology to defeat sophisticated air defenses.

Raytheon was picked to build the LRSO in April 2020, when the Air Force in a surprise move chose Raytheon as the prime contractor over a bid from Lockheed Martin months before a decision was expected.

People are also reading…

Each company had been awarded competitive LRSO technology-development contracts of about $900 million in 2017, with the work expected to stretch into 2022.

On July 1, the Pentagon announced that the Air Force Nuclear Weapons Center at Eglin Air Force Base, Florida, had awarded Raytheon an initial $2 billion contract for the engineering and manufacturing development phase of the LRSO program, to build and demonstrate a missile ready for full production by February 2027.

Digital design

Over time, contracts to produce 1,000 LRSO missiles could reach $10 billion, congressional budget researchers estimated in 2017. Planned upgrades to a thermonuclear warhead slated for use on the LRSO could cost at least $10 billion.

Raytheon declined to comment in detail on the LRSO program, referring questions to the Air Force, and many program details remain classified.

In a statement to the Star, Paul Ferraro, vice president of Air Power at Raytheon Missiles & Defense, credited the companyтs selection as sole-source contractor on the program to a focus on тdigital engineeringт and close collaboration with the Air Force.

тTransitioning to the (engineering and manufacturing development) phase is a big step toward delivering this critical capability to the Air Force to strengthen our nationтs deterrence posture,т he said.

During an investor day presentation for parent company Raytheon Technologies Corp. in May, Raytheon Missiles & Defense President Wes Kremer broke down how the company is using extensive computer simulations to virtually тflyт LRSO components millions of miles a day.

тEvery single night, this code is compiled, the updates are made, the inputs from our vendors are made and we fly that missile 6 million miles in the highest threat environments in the world in a completely virtual environment,т Kremer said.

The next morning, he said, Raytheon engineers and Air Force program officials can review the data and compare it to key measures such as of survivability, range and the probability of a successful mission.

тIt means we can not only go faster in development, but because of the high fidelity of the environments that we fly in, we can reduce test times and we can better predict failures in the future,т resulting in lower operating costs, faster overall development times and тthe ability to keep pace with the threat,т Kremer said.

Raytheon, which makes many of the nationтs front-line missile systems, is no stranger to cruise missiles т guided surface-attack missiles that typically fly and maneuver at low altitude to avoid radar detection.

The company, the УлшжжБВЅ regionтs biggest employer with more than 13,000 local workers, has supplied the Navy with the combat-proven Tomahawk Land Attack Missile for decades.

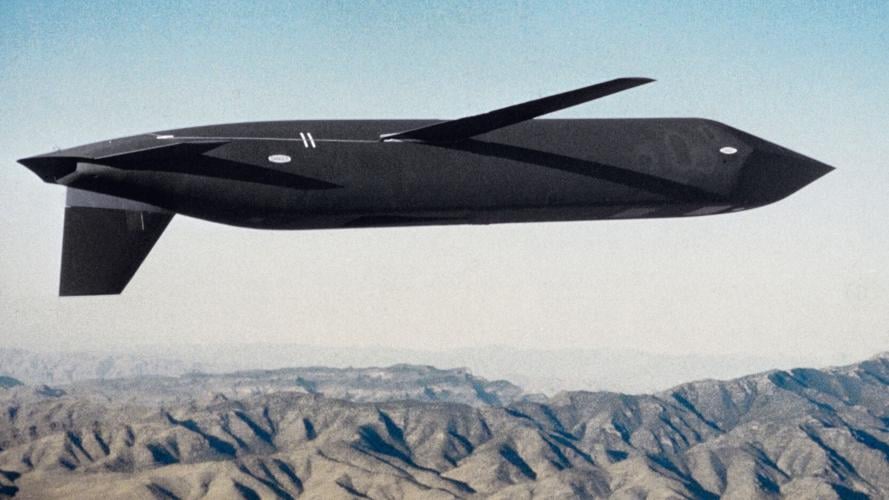

Raytheon also produced the last attempted upgrade to the AGM-86 Air-Launched Cruise Missile: the AGM-129 Advanced Cruise Missile, a nuclear-tipped weapon originally developed by General Dynamics and later acquired by Raytheon with other missile lines from Hughes Aircraft in 1997.

Raytheon's AGM-129 Advanced Cruise Missile was originally developed by General Dynamics and was in service from 1990 to 2012.

The AGM-129, which featured a radar-evading stealth design, and navigation systems similar to Raytheonтs Tomahawks, was flown aboard B-52 bombers as part of the nationтs air-based strategic nuclear deterrent from 1990 until it was formally retired in 2012.

Production orders for the advanced cruise missile were cut drastically in the early 2000s to help comply with a Russian arms-reduction treaty, and the Air Force later dropped planned life-extending upgrades to missiles in service amid reliability concerns.

Cash, criticism

Meanwhile, the LRSO program has won the support of the Biden administration, which has requested $609 million in funding for the development program in fiscal 2022.

But in its markup of the fiscal 2022 defense budget released July 13, the House Appropriations Committee proposed cutting the LRSO budget request by $28 million, to $581 million, while requiring quarterly budget updates. The Senate Appropriations Committee has yet to complete its markup of the defense spending bill.

Critics including former Defense Secretary William Perry and groups such as the Arms Control Association and the Project for Government Oversightтs Center for Defense Information have said the new nuclear-tipped cruise missile is unnecessary and could be destabilizing, since current conventional cruise missiles could be mistaken for a nuclear version and spark unintended nuclear war.

In 2017, nine Democratic senators including Sen. Diane Feinstein moved to delay LRSO funding as the Trump administration completed its Nuclear Posture Review, which subsequently endorsed the LRSO.

Other critics say the weapon is redundant in light of other land-attack options and is too costly.

But the Air Force and some defense analysts say the LRSO is a necessary component of the тnuclear triadт of weapons that also includes submarine-launched ballistic missiles and land-based intercontinental missiles.

тWithout LRSO, the nuclear part of the bomber force will begin to whither away,т said Loren Thompson, chief operating officer of the Lexington Institute, a Virginia-based policy institute.

тThe problem with the B-52s is that they are 60 years old, and the only way they can reach nuclear targets is cruise missiles, but unfortunately their cruise missiles are too old and too easy to shoot down.т

Thompson, who notes that Raytheon and other companies with a stake in nuclear modernization contribute to his think tank, said having an air-launched nuclear capability is critical because bombers can be recalled, unlike missiles launched from submarines or ground silos.

тOnce you launch a missile from a submarine or a silo, itтs gone, itтs not coming back,т Thompson said. тWhen you launch a bomber, you can recall it or retarget it.т

The LRSO is being designed to be carried not only by the B-52 but also the new B-21 Raider, a stealthy, bat-wing bomber set to begin replacing the B-2 Spirit stealth bomber around 2027.

Flying unseen

Though details of the Pentagonтs requirements for the LRSO, as well as Raytheonтs design, remain under wraps, the LRSO will likely fly at subsonic speeds and feature a stealthy design, with тlow observableт features such as airframe shapes and surface angles designed to deflect signals away from radar emitters, and signal-absorbing materials.

тIt canтt be seen on Russian or Chinese radar, in fact, thatтs one reason itтs subsonic, because once you go supersonic, itтs easier to see,т Thompson said, citing the heat signature and other attributes of supersonic missiles that show up on enemy sensors.

The LRSO is expected to have a range of at least 1,500 miles and will carry the W80-4 thermonuclear warhead, an upgraded version of a relatively small low to intermediate yield warhead in service since 1981.

Roughly 31 inches long and about a foot in diameter, the W80 can be set to achieve a blast equal to 5 or 150 thousand tons, or kilotons, of TNT. The atomic bomb that devastated Hiroshima, Japan, in 1945 carried the explosive power of 20 kilotons of TNT.

Contact senior reporter David Wichner at dwichner@tucson.com or 573-4181. On Twitter: @dwichner. On Facebook: