The previous home of the УлшжжБВЅ featured big plate-glass windows on its north face, allowing passersby to peer in.

That was at 208 N. Stone Ave., a building that no longer exists on a downtown corner that has disappeared.

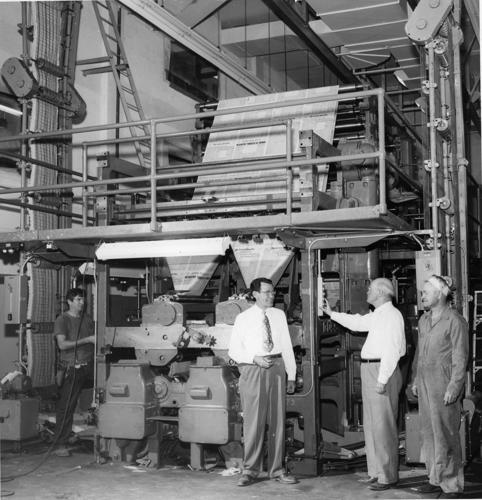

The building housed the Star and the УлшжжБВЅ Citizen until 1973, and the windows on the ground floor, facing the now-extinct East Council Street, allowed public viewing of a miracle т the massive, churning printing presses in motion, pushing out two papers daily.

The presses were a point of pride not just for the newspapers that owned them but also for the city itself, a sign that this little desert burg really was someplace. Thatтs because printing presses, then and now, take information and turn it into a physical object, an act of alchemy that has never ceased to amaze many of us.

People are also reading…

Thatтs one of the reasons youтll see so much nostalgia in the paper today about the closure of the Starтs printing press after the run Sunday night, with printing moving to Phoenix on Monday. These magical industrial machines make something you can hold in your hands т a newspaper т that was the main vehicle for mass communication in УлшжжБВЅ for more than a century.

The smell of ink and the powerful vibrations of the presses make you feel something big is happening, that words and images are turning tangible.

This wizardry has cast a spell on local people for decades. Since I arrived in 1997, Iтve seen numerous tour groups walking through the newsroom and back to gaze at the presses. The Feb. 24, 1955, Rodeo Edition of the УлшжжБВЅ included a feature story on the presses at the Stone Avenue site. The headline was тMagic Is The Work of TNI Press.т

According to a recent report, nearly 20% of all U.S. newspapers have closed since 2004, and the industry has lost 47% of its jobs.

On Aug. 20, 1973, the front page of the Star featured a photo of the old building and a caption headed тThe Rumble is Stilled.т The caption went on, тNo longer will the daily rumble of the presses and the clickity clack of typewriters and teletype machines reverberate from the old pink building at 208 N. Stone Ave.т

That day the Star and Citizen т and their joint business entity, УлшжжБВЅ УлшжжБВЅpapers Inc. т moved to the new building where the Star is still housed, 4850 S. Park Ave. Since then, that building has been known to employees and many УлшжжБВЅans simply as тThe Plant.т

Itтs a plant, not just a bunch of offices, because something has been made here, and assembled, and shipped out. A manufacturing process takes place here т till Monday.

That day in 1973, we celebrated the new press in the printed paper. This was our first offset press, switching us from a molten-lead based process to a photographic process for reproducing pages.

тAt that time there was so much pride in the process of printing,т director of printing operations John Lundgren said.

The Goss Metro offset press switched on in August 1973 is the same one set to go quiet today т too expensive to maintain and run when УлшжжБВЅ has only one daily newspaper and readership is quickly shifting online.

I made a pilgrimage back to the press Thursday afternoon to visit with the pressmen. Theyтve been getting a lot of visits lately, including one from James Krakowiak, who was a pressman for more than 40 years and is deaf. All the current pressmen knew at least a little sign language because they worked with him and another deaf employee. On Thursday, they spelled out words with their hands to reminisce with Krakowiak.

The pressmen have seen the signs that this day was coming for a decade or more, at least since the Citizen closed in May 2009, pressman Jeff Aronhalt told me. But they held on to the job and the pride of creation.

тThe neat thing about this job is you walk around here and pick up something that you made,т Aronhalt said.

Supervisor Jeff Aronhalt has worked with the УлшжжБВЅтs thundering presses for 41 years.

Of course these are people who are fans of the object, the printed paper, that has been their sustenance.

тYou can still make a webpage, but you canтt hold that in your hand,т press supervisor Ben Taylor said.

For those of us in the business, the fact that we wonтt be making that thing in УлшжжБВЅ anymore is painful and symbolic of the disorienting times weтre in. The spread of information has moved online, which is good in that itтs saving quite a few trees. It is also making it possible for anyone to become a publisher. Thatтs a good thing in many respects, but the lack of a barrier to entry has down sides, too.

You canтt hold a webpage in your hand, notes Ben Taylor, a press supervisor who has put in 17 years at the Star.

This struck me especially hard last summer during a strange, months-long episode. Marana-area resident Michael Lewis Arthur Meyer was attracting thousands of online viewers as he spread the baseless conspiracy theory that he had discovered a camp on УлшжжБВЅтs southwest side where children were being sex-trafficked. It wasnтt true, but he didnтt need a printing press to spread his fantasies. He just used Facebook Live and attracted a huge audience, soliciting donations of gift cards and materials all the while.

The same sort of conspiracism and fantasy has exploded across social media т at the same time some excellent journalism by professionals and citizens alike has appeared online. When you donтt need to own a press to print a paper to communicate with a massive audience, anything goes.

The great leveler of the internet means weтll no longer really be working in a тplantт come Monday. It will just be a newsroom and offices.

Itтs still a great way to make a living, but it will be diminished without the rumble of the press, the smell of fresh ink and the satisfaction of picking up a paper that we made here.

The people who print, package and transport newspapers at the Star

The people who print, package and transport newspapers at the УлшжжБВЅ

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Jeff Aronhalt. Press Supervisor. 41 years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Debbie George. Packaging: Insert Loader. Forty years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Irma Camacho. Packaging: Inserter. Twenty-three years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

George Duarte. Transportation: CDL Driver. Thirteen years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Joanna Jacobs. Packaging: Forklift Driver. Thirty years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Steve Wood. Press Maintenance Technician. 10 years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Marco Fierro. Folder Operator. 35 years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Damian Nunez. Operations Electronic Specialist. 32 with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Nancy Loyola. Packaging Center Supervisor. 26 years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Roger Rinehart. Press Operator. Thirty-six years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Ariel Melena. Press Trainee. Four years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Kevin McCaffrey. Pressman. Thirteen years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Hector Alegria. Pressman. Nineteen years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Richard Buelna. Pressman. Twenty-four years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Gutberto Castelo. Pressman. Fourteen years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Temujin Gerritson. Pressman. Fourteen years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Chris Barrett. Press Supervisor. Eighteen years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Erik Vigil. Pressman. Two years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Mario Smith. Pressman. Seventeen years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Benjamin Taylor. Press Supervisor. Seventeen years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Kirk Molett. Warehouse Operator. Thirty-four years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Maricela Navarro. Lead Person: Packaging. Twenty years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Julio Rios. Transportation: Lead Driver. Twelve years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Kerry Vallen. Transportation: Lead Driver. Thirty-four years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Sherrie Holden. Packaging: Lead Line Person. Five years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Julia Espriu. Packaging: Lead Person. Twenty-one years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Leila Castillo. Packaging: Inserter. One year with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Oralia Garcia. Packaging: Inserter. Eighteen years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Jorge Gonzalez. Packaging: Inserter. Three years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Rudy Marquez. Packaging: Inserter. Twenty-seven years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Luis Balderrama. Packaging: DOT Driver. Eleven years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Hector Espriu. Packaging Center Technician II. Twenty years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Adam Fortado. Packaging: Machine Operator. Two years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Travis Salazar. Packaging: Inserter. Six years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Josh Cruikshank. Packaging: Inserter. Five years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Nathan Lamadrid. Packaging: Inserter. Three years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Cynthia Overton-Ellis. Packaging: Lead Person. Six years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Aaron Montiel. Packaging: Machine Operator. Four years with the УлшжжБВЅ.

УлшжжБВЅ press, packaging, transportation employees

Ted Furphy. Press Maintenance Technician. Twenty-one years with the УлшжжБВЅ.Т