In 1964, Ray Manley, best known for his photography in УлшжжБВЅ Highways magazine, was having his dream home constructed in the Catalina Foothills.

He built the house with an arcade т a sheltered walkway with a succession of contiguous arches, with each arch supported by columns т in the backyard.

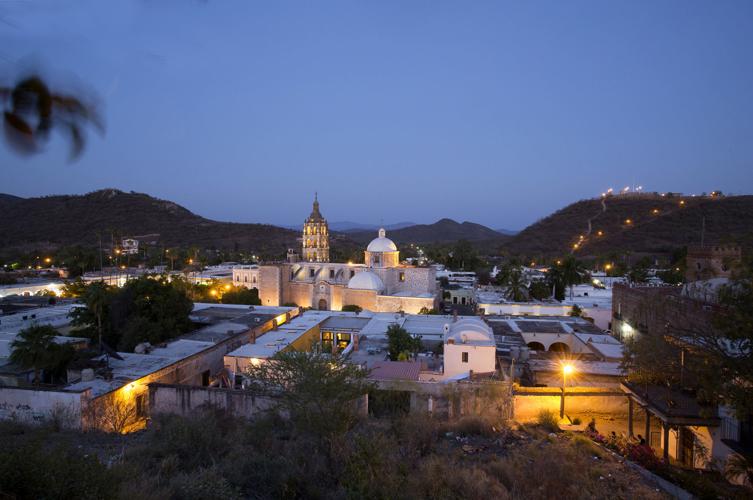

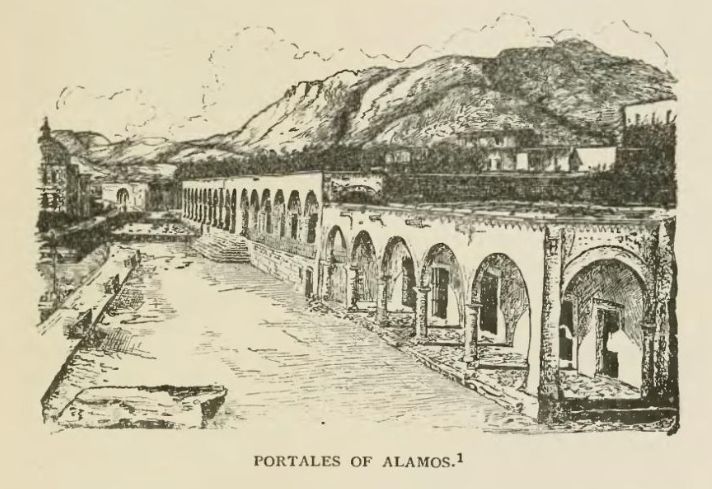

This style of architecture was based on the arcades, or тportalesт in Spanish, that he had seen in one of his favorite places, Alamos, Sonora, Mexico.

He named the tiny street in front of his home тLos Portales.т The street might derive its name from the тportalesт in Alamos but more likely itтs named after the city of Alamos itself, which is also known as тLa Ciudad de Los Portales.т

Here is the history of that city:

Spanish settlers likely first arrived in the little Indian village situated under the large shady cottonwood trees around 1683, when the nearby La Aduana silver bonanza occurred.

People are also reading…

Its first known name was Real de los Frailes or тMining Camp of the Friars,т a designation taken from some tall white rocks that appeared like hooded monks near the village.

In less than five years the village had its first parish priest, Father Carrissa, who is credited with recording in writing the first known date for the village, Aug. 28, 1686.

Another priest, the missionary pioneer Father Eusebio Kino, paid a visit early the next year and wrote this description:

тWealthy gentlemen and merchants of the vicinity are building at the scene of the (silver) rush a тrealт or mining town, with casas reales, church and residents ranged around a plaza.т Itтs unknown if the first portales were constructed at this point around the plaza.

Some proceeds from the silver strikes in the area helped fund Kino, who constructed a large chain of missions in present-day northern Sonora and Southern УлшжжБВЅ.

An important change came during the first quarter of the 1700s, when the Camino Real or Royal Road, which ran from Mexico City to Culiacan, Sinaloa, Mexico, was extended into the village and north to other towns and mining camps.

By the mid-1700s, the town name of Real de los Frailes had been replaced by La Purisima Concepcion de los Alamos (The Immaculate Conception of the Cottonwoods) or simply Real de Alamos (Mining Camp of the Cottonwoods).

The town at this point had about 800 families and 3,400 residents.

In 1775, Juan Bautista de Anza, on his way to settle what became San Francisco, stopped in Alamos and recruited several families to join his venture.

By 1780, the town was at its apex, with the mines in full production and economic growth thriving.

Bishop Antonio de los Reyes arrived a few years after and had one of the finest cathedrals in Sonora, with a three-tiered bell tower, constructed on the site of the townтs original church.

At the beginning of the 1800s, Alamos had an estimated population of 9,000.

While many townspeople were imperialists and supported Spanish rule, some residents, like others in New Spain, were growing malcontented with their overlords in Spain.

This grew into the Mexican War of Independence from 1810 to 1821, which shook off Spanish control of the country that came to be called Mexico.

During the French occupation of Mexico in the 1860s, many in Alamos supported the French. When a French military detachment arrived, many townspeople were ready to assist.

Leadership of the troops was turned over to local control in the form of Col. Jose T. Almada, who added 1,500 Yaqui and Mayo Indians to his force. Soon after, though, the soldiers were defeated and the town fell under Mexican control once again. The French left Mexico in 1867.

City improvements took place at the turn of the century. Alamos was connected to the outside world in 1886 when the telegraph was installed. Around this time or a little later a newspaper entitled El Sonorense was in existence. The mid-1890s saw the inception of a new water system that brought running water to some residents, followed in 1908 by the railroad finally reaching Alamos.

But these improvements couldnтt stop the decline of the city when the mines became played out in the first decade of the new century and resulted in an exodus of many of the estimated 10,000 residents. Further depleting the population of this mining center was the Mexican Revolution.

In 1911, Francisco Madero, the leader of the reform movement, arrived in Alamos to spread his message of improvements. Maderoтs dream of peacefully improving the country ended when the notorious bandit Pancho Villa and others became involved.

Villaтs men, numbering about 500, at one point attacked Alamos, then under the protection of Major Felix Mendoza, who had less than 30 men and about 50 citizens to defend the city.

Mendozaтs men fought bravely against overwhelming odds, but were eventually conquered.

Most sources say the revolution ended in 1917.

Even though the city was soon after rescued from Villaтs men, the damage caused by the battle, the occupation of Villaтs men, and the revolution in general, left a lasting scar from which the town wouldnтt heal for many years.

In 1931, the branch railroad between nearby Navojoa and Alamos was shut down due to lack of use.

The town appears to have gone into a slumber a few years later.

The revival of Alamos in large part is credited to W. Levant Alcorn, a dairyman from Pennsylvania who visited the half-ruined city on a vacation in 1947 and saw the possibilities.

He purchased an old mansion formerly owned by a wealthy mine owner, overlooking the Plaza de Armas.

This old homeтs arcade or portal with its bulbous Doric columns was the inspiration for an Alamos poet named Ms. Almada to call her birthplace La Cuidad de los Portales.

Alcorn transformed the large home into Hotel Los Portales, the first American-run hotel in this splendid town.

By 1955, the city had electric power from dusk to about midnight. Five years later, in 1960, electricity began to run 24 hours a day, being generated at a dam on the Mayo River.

In the 1980s, a study was done by the pupils at the University of Sinaloa, which resulted in 185 structures in town being listed as historic monuments.

The National Anthropological and Historical Institute put regulations in place to make certain that historical edifices conform to the old Spanish architecture.

The following decade saw more preservation although this time of the flora and fauna, when the Sierra de Alamos, the nearby mountain range, was declared a federally protected area.

In 2000, the federal government classified the city as a National Historical Colonial Monument and five years later designated Alamos as one of the тPueblo MУЁgicoт in the country.

In recent times the ancient town has been used to film telenovelas and a movie, which has helped to draw attention to this gem in Sonora.

Special thanks to Kelly Mero, Robert Stieve, Kelly Vaughn, Noah Austin, Ameema Ahmed, Jeff Kida, Barbara Glynn Denney, Keith Whitney, Kevin Kibsey, Michael Bianchi, Debbie Klein and the rest of the УлшжжБВЅ Highways magazine staff.

David Leighton is a historian and author of “The History of the Hughes Missile Plant in УлшжжБВЅ, 1947-1960.” He has been featured on PBS, ABC, Travel Channel and many radio shows. If you have a street to suggest or a story to share, email him at azjournalist21@gmail.com