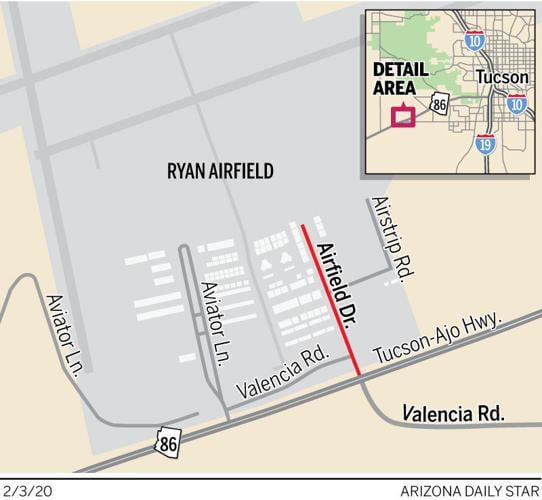

Airfield Drive, a street located southwest of УлшжжБВЅ off of Ajo Highway, leads into its namesake, Ryan Airfield. In turn, this airfield derives its name from the now-defunct Ryan School of Aeronautics of УлшжжБВЅ, whose founder was one of the most important early aviation pioneers, T. Claude Ryan.

Ryan was born in 1898 in Kansas. Like many boys of his time, he read the aviation series commonly found in magazines. But it wasnтt until the 1911 Cal P. Rogers 84-day transcontinental flight (which included a stop in УлшжжБВЅ) that he saw an airplane in real life.

In 1917, after his family moved to California, he attended the American School of Aviation in Venice, a school with two run-down airplanes; a flight instructor who had barely flown one solo in his life; and a balance sheet that had more minuses than pluses.

Ryanтs final day at the struggling school ended in an impromptu solo flight at an altitude of 30 feet with a landing that destroyed the propeller and finally bankrupted the school.

People are also reading…

His crash course in flying led to acceptance in the U.S Army Air Service, a predecessor to the U.S. Air Force, and real flight instruction. Upon graduation, Ryan volunteered for a special program to fly patrols over forest land in northern California, searching for wildfires during the fire season.

In 1922, he was discharged from the Air Service and reentered civilian life in Southern California. He decided to begin his own aviation business, putting a тfor saleт sign on his car and scraping together his savings to raise capital.

Soon after, he learned that a pilot had been running a successful flying business at an airfield near San Diego Bay until he was caught smuggling Chinese immigrants across the U.S.-Mexican border. The field was now available to lease.

Ryan purchased a Curtiss JN-4 тJennyт biplane and took over the old airfield. In time, he moved his business and his now two Jennies to the new тRyan Flying Companyт airport, further up the bay. In 1923-24, when the government sold off its WWI warbirds, Ryan obtained six Standard J-1 biplanes and turned these two-place open cockpit aircraft into five-place cabin airplanes gaining the name Ryan-Standard airplanes. These planes were used in tourist flights over San Diego.

Ryan also was involved in the Ryan School of Aviation at the same airport. One of his students was a wealthy man, B.F. Mahoney, who talked Ryan into going into business with him to form тRyan Airlines Inc.т and provide the first ever, year-round passenger airplane line, which operated on a regular schedule in the U.S. The тLos Angeles-San Diego Air Lineт ran everyday between the two cities.

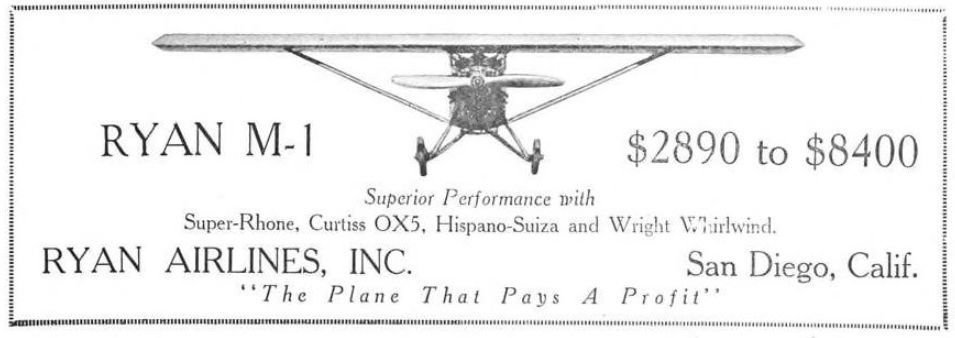

The same year, Ryan, knowing that the Postal Service would soon turn over the airmail service to private contractors, designed and built an airplane with greater speed and carrying capacity than planes being used at the time. This aircraft was known as the Ryan M-1 plane, and was followed by the Ryan M-2 and the Ryan Bluebird.

Before the end of 1926, Ryan sold the manufacturing enterprise to Mahoney, but said he would remain with the business for at least four months as the manager. Early the next year, Ryan and his staff built the Spirit of St. Louis for Charles Lindbergh, who flew it from New York City to Paris and into the history books.

On Feb. 18, 1928, Ryan wed Gladys Bowen of San Diego and honeymooned in Europe. The couple would have sons David, Jerry and Stephen.

In 1931, Ryan incorporated the Ryan Aeronautical Co. and the next year its training activities moved to Lindbergh Field (San Diego International Airport). Soon after, Ryan and Millard Boyd designed the first Ryan S-T with production of the plane beginning in 1935. The Ryan STM military trainer was also produced.

In 1938, the U.S. Army Air Corps began looking for ways to increase the number of trained military pilots for potential involvement in the upcoming war. They turned to established civilian flight schools like the Ryan School of Aeronautics in San Diego to fill this void.

Two years later, Ryan was asked to open a second school for training military pilots, this time in Hemet, California.

After the attack by the Japanese on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, in December 1941, the military decided that an inland training site was preferred over the coastal city of San Diego. УлшжжБВЅтs clear skies offered a perfect place.

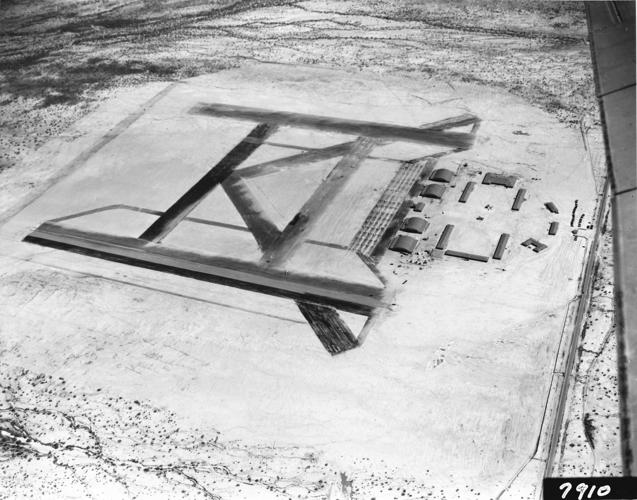

Ground was broken for the new site, 15 miles southwest of УлшжжБВЅ, on Ajo Highway, in June 1942. In late July 1942, Bob Kerlinger, civilian director of flying, and Maj. Donald Haarman, military commanding officer of the Ryan School of Aeronautics of УлшжжБВЅ, stood and watched dust storms swirling around half-completed wooden buildings with carpenters working feverishly to complete them before the cadets arrived from San Diego in a couple of days.

The buildings had no air conditioning and employees worked in offices that lacked roofs and suffered in the brutal heat.

The cooks prepared meals in a kitchen without flooring, a roof, gas, electricity or even plumbing. The cadets spent days of rigorous physical training and flight practice without the facilities for washing except a pail of water.

At this time there were no facilities in place for protecting the school from dust and it was everywhere. Heaps of it blew into cooksт stoves, clerksт typewriters and mechanicsт tool boxes. Trainees soon learned that when they did a roll in their planes they would be blinded by dust from the floor of the cockpit. Pest control was another issue as rattlesnakes, scorpions and Gila monsters visited their new neighbors, taking up residency but refusing to sign on as cadets although they soon received their marching orders and departed the airfield.

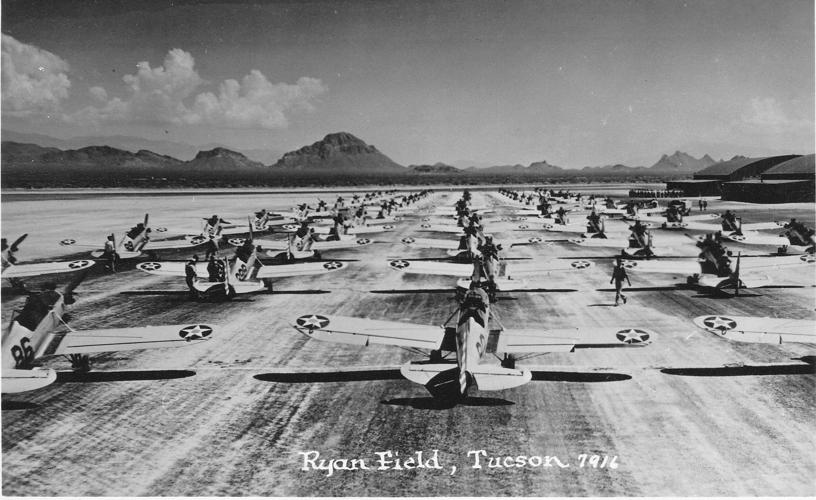

By August 1942, the school was training its first pilots in the Ryan P-22 aircraft, which held up surprisingly well to the heat, wind and dust storms.

However, when plane failure or pilot error did occur it could be deadly, like a mid-air crash in December 1942 that killed four people.

In July 1943, Ryan flew from San Diego into УлшжжБВЅ to celebrate the one-year anniversary of the school. At the time Ryan was vice president of the Aircraft War Production Council, West Coast.

By this time the airfield was equipped with electricity, inter-office phones, modern plumbing and air conditioning. Every inch of the ground was covered with asphalt.

The cadet barracks were clean, the mess halls were spotless and the Army hospital stocked with equipment.

There was also a PX, classrooms, and a victory garden. The following year the school closed.

While УлшжжБВЅтs Ryan team was running the aviation school, Ryan received a secret contract to develop the U.S. Navyтs first jet aircraft, the Ryan Fireball. The Fireball was unique, with a propeller engine in the nose and a jet engine in the tail, although it never saw war action.

The 1950s saw Ryan and his company working on new technology such as the first Air Force air-to-air research missile known as the Ryan Firebird, which was beat out by the Hughes Aircraft Co.тs Falcon missile produced in УлшжжБВЅ. The following decade witnessed some of the companyтs aerospace technology being utilized in the Apollo 11 moon landing in 1968, and soon after it was sold to Teledyne and became Teledyne Ryan, eventually being integrated into Northrop Grumman in 1999.

Ryan and a son formed the Ryson Corp., a design firm, building powered glider planes flown by remote control, until the time of his death in 1982.

Special thanks to Ken Perry of Ryan Airfield, David Hatfield of УлшжжБВЅ Airport Authority and Andrew Boehly of Pima Air and Space Museum, for research assistance on this article.

David Leighton is a historian and author of “The History of the Hughes Missile Plant in УлшжжБВЅ, 1947-1960.” He has been featured on PBS, ABC, Travel Channel, various radio shows, and his work has appeared in УлшжжБВЅ Highways. If you have a street to suggest or a story to share, email him at azjournalist21@gmail.com.